Mickey Mantle should have been my dad. Then I could have been hanging around the New York Yankee clubhouse in 1961, the Yankees’ greatest season. At least, that’s what I thought when I was 10.

My dad, about age 3. His mother used to enter him in “cute baby” contests which were popular store promotions in the 20s.

If my dad wasn’t going to be the New York center fielder, at least he could have had a career I could brag about at school. Other kids’ dads were doctors, lawyers, builders and realtors. Even working as an insurance man, lining up with dozens and dozens of other dads on Farmington Avenue every weekday at 8 a.m., taking the bus to downtown Hartford would have been better for a kid to brag about than the job my dad had. He was a ceiling tile salesman.

My dad sold stuff that improved the acoustics and look of grocery store ceilings. He drove around southern New England and upstate New York in the company car – usually a canary yellow Plymouth station wagon that was the family’s only vehicle – selling tile and the company’s original product, wall insulation made out of wood fibers, to contractors putting up shopping centers and schools.

I had no issues with my mom. She was the prettiest mom in the neighborhood and of all the moms of the kids in my elementary school. She made the best pizza and the best lasagna, and her cakes were works of art.

One of my mother’s musically correct works of art.

But growing up in the 1950s, your dad – along with his job – was the person who defined you before you began to define yourself. And an ordinary dad was a status killer. At least mine didn’t have an ordinary name. As far back as I can remember, he was Doom.

Some might have figured he got the name because he played college football and was big for his time: 6 feet 2 inches tall and usually about 210 pounds. And he didn’t have the demeanor of a Dad who made suggestions. When he told you to do something, you did it. He only had to say, “Don’t buck me” to me once. So I didn’t.

But that’s not why we called him Doom.

He got that name when we were renting the right half of a large Victorian house in the bucolic, upstate New York village of Altamont, twenty miles outside of Albany. Four two-story pillars defined the front porch, and inside our front door, a grand, three-level staircase took twenty-four steps and two turns to reach the second story. We had moved there from Levittown, N.Y., where first Carol, then Page and finally, I was born. Liz showed up in Altamont. That was a bit of a shock to me, no longer being the baby. But I got over it – when I was about 25.

We rented the right half of this house in Altamont, N.Y., 1952-57.

The staircase was so wide and tall, there was room for a closet underneath, a closet big enough for three kids hiding from a parent on the warpath to find refuge. So there we were, with our dad charging down the stairs above, searching for us. I don’t remember what we had done, but odds are pretty good that Page was behind the mischief.

“Doombala, doombala, doombala,” Page whispered, in exact rhythm to our dad’s footsteps as he raced down the old stairs. We tried to hold back our laughter, which would give away our position, but he couldn’t resist repeating: “Doombala, doombala, doombala.”

We laughed so hard, we rolled out of the closet, gasping for air.

Our dad found us, but he couldn’t stay mad at three laughing children. When we told him what was so funny, he laughed, too. Page began calling him Doombala, which we liked, but it was too long for everyday use. It was soon shortened to Doom, a name he came to regard with pride. After that, we never called him anything else.

Doom’s family was English, which was about as exciting to us as his being a ceiling tile salesman. In the Northeast, ethnicity mattered. And though we grew up in a waspy suburb, we wanted some ethnic identity. When everyone else is claiming Jewish, Irish, German (though not so popular in the ’50s), or Polish heritage, English was boring and useless, especially when you needed your heritage to bond – or fight – with others. Not a lot of English tough guys at school or on the block.

Our mom was 100 percent Italian, so we used that. It made me tougher, at least I hoped so, in the eyes of others. Not that I was, or that the Italians had acquitted themselves so well in the war, but at least I could pretend to have a connection to the Italian gangster stereotype, then popular in the movies.

The Italian relatives (my mom’s parents and her uncle) on a Sunday visit to our first house, Levittown, N.Y., 1949.

Years later we learned that the English side of the family had a pretty good back story, but Doom’s parents were long dead by the time any of us were born, and anyway, it still wasn’t nearly enough to keep from getting beaten up. His brother, Hugh, was nine years older than he and lived in Pennsylvania. We visited a bit when we were all really young but rarely saw that side of the family as we grew up.

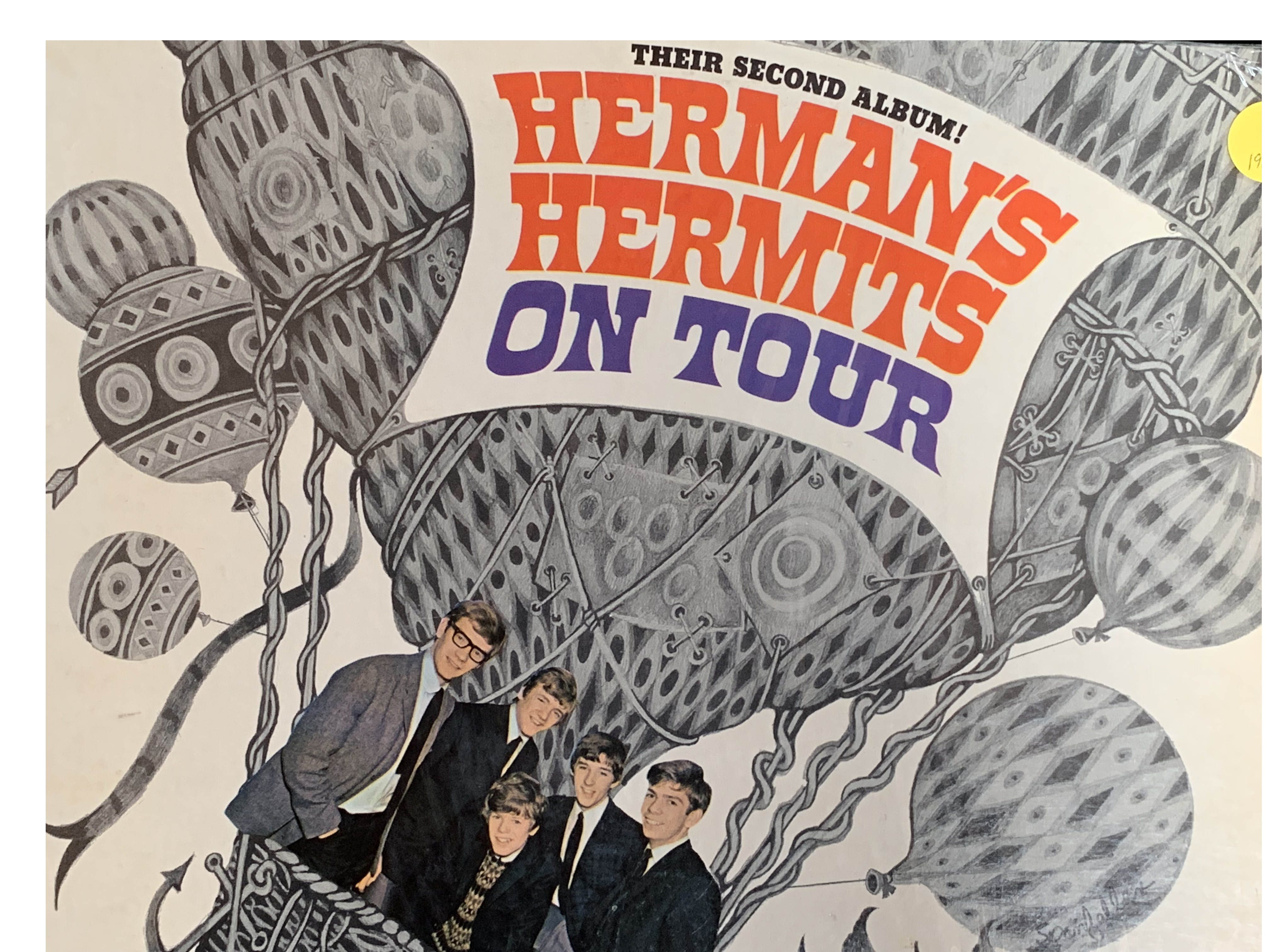

There were fairly regular visits, though, from Doom’s great aunt Daisy and her brother, Harry, Brits who lived in New York City. They spoke with strong accents, but I didn’t realize how tight their tie was to the mother country. Until … one Christmas, when I’d gotten a Herman’s Hermits record featuring “I’m Henry the VIII, I am.”

Uncle Harry, as always lounging around the house in his tweed sport coat and bow tie, knew the tune and started singing along.

“We used to sing it in the foxholes during World War I,” he answered my astonished look.

I reacted badly. I was 14, and this was my music. Or so I thought. I stopped playing the record until the holidays were over and Uncle Harry was gone. It was only much later that I wished I had picked up the needle, turned off the record player and asked Unk about the war rather than stalking off to my room.

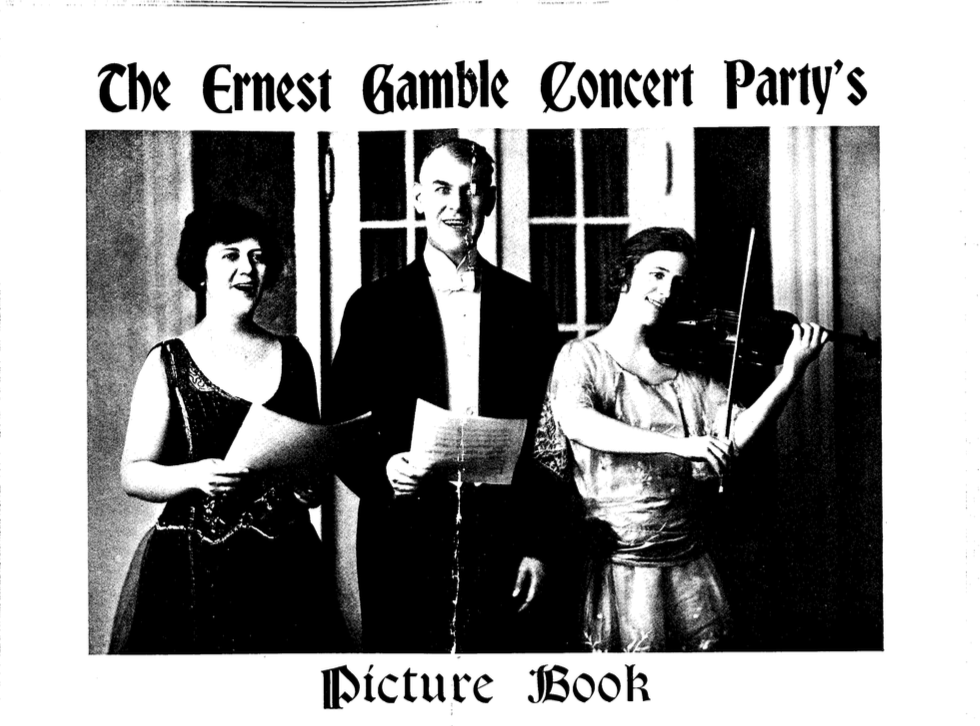

Doom’s mom, Lela Page, was Canadian. In 1907, she was 29, at home, and single without prospects; the only exciting thing in her life was following the exploits of her sister, Verna, and her brother-in-law, Ernest Gamble, as they performed internationally as the Ernest Gamble Concert Party.

The cover of the group’s promotional material at the start of their tour in 1907.

Newspaper writers across the globe praised their talents and noted Verna’s violin playing and beauty, though they seemed to lavish almost as much praise on her violin as on her playing. They were home in Canada, rehearsing for an engagement at the Panama Canal, where they would be entertaining the guys who were building it, and invited Lela to come along.

Lela could play the piano a bit – not at her sister’s talent level, but enough to warm up the crowd – so she joined them. And that’s where she met Hugh Sivell, an Englishman in his early 20s, working at the commissary. He had taken the job for the adventure and good pay. After a brief courtship, Lela and Hugh married and moved to the States, settling in Milford, Connecticut. Hugh Jr. came along fairly quickly, followed by John – Doom – nine years later.

The family did fine during the ’20s, but things got a bit tougher with the Depression. Doom was entering his teens when his older brother left for college. A few years later, his father, Hugh Sr. got cancer and died at age 49.

Despite going to school with just lettuce sandwiches – that was Doom’s big depression story, along with brown sugar bread for desert – Doom eventually filled out that 6 foot 2 inch frame. He became quite a good swimmer and worked as a lifeguard and swim teacher.

And though he hadn’t played much football in high school, he managed to convince the coaches at Hampden-Sydney College to offer him a scholarship, sight unseen. They were rewarded with four years of hard work and play, and Doom was a league all-star and team captain in his senior year.

He also worked hard to keep his grades up – double majoring in Spanish and chemistry. The war was on, and he needed the good grades so he could, as he said, enlist as an officer and give orders rather than go in as a grunt and take them. In 1943 he graduated and was sent to the Naval training school at Columbia University in New York where the government created 9,000 of the “90 day wonders” a year that were needed to man the ships in the Pacific theater.

Doom spent three months at the U.S Naval Reserve Midshipmen School at Columbia University in 1943 before shipping out.

After he completed his training, he was bound for the Pacific to serve on a supply ship as a lieutenant. But trying to get a train to the west coast and his ship, Doom had a ticketing problem at New York’s Penn Station. One of the ticket agents, a young Italian woman from Brooklyn, was both helpful and attractive.

While his buddy talked to her about how the problem could be solved, Doom snuck around behind the desk and checked out her legs (he approved, but the fact that he didn’t add that detail until I was 40, married, and with kids of my own tells you what a proper gentleman he was). Anyway. It was going to be several hours before their train would depart, so Doom asked the ticket agent for a date.

Good thing for him – and me … and Carol and Page and Liz – she said yes.

Next week: Page finds trouble.

Categories: My story