The first time I heard about the “free” hard rolls, I was in the back yard with a bunch of friends. Doom had put up a monkey swing in the big elm. He tied a thick rope to a branch high up in the tree and at the bottom, he threaded the rope through the seat, a one-foot by eight-inch board and knotted it.

We would climb up about 10 to 12 feet to a crotch in the tree, someone would swing the rope up while you balanced with one hand and tried to grab the rope with the other. Then you leaped into the abyss. You could either sit or stand on the board.

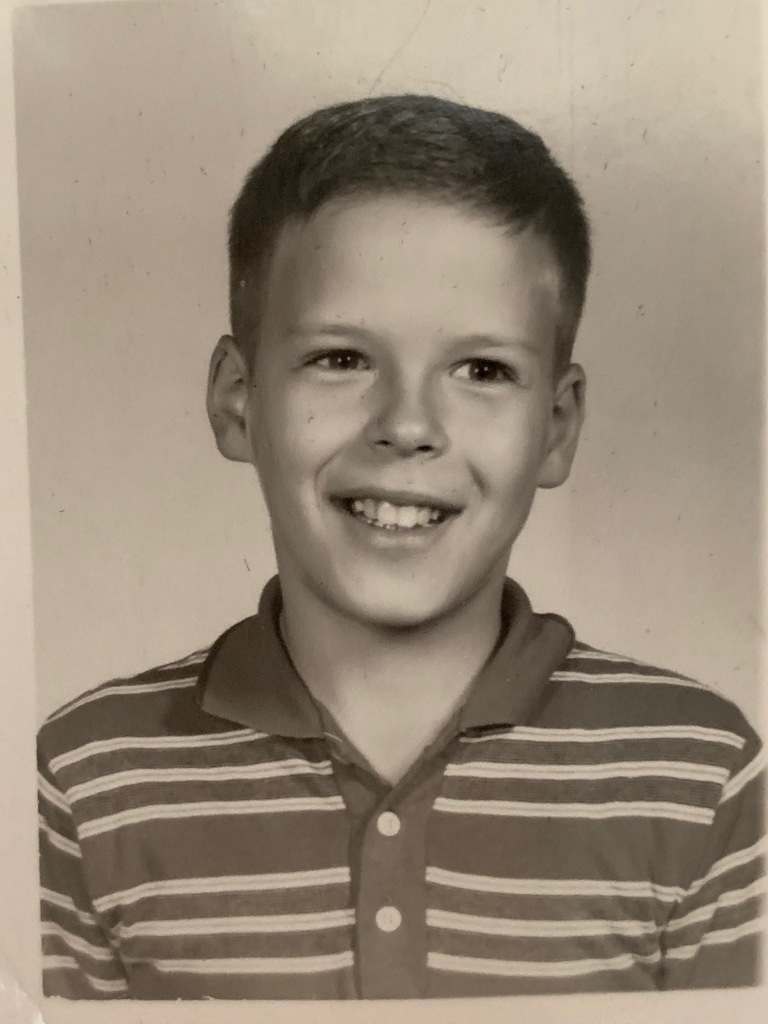

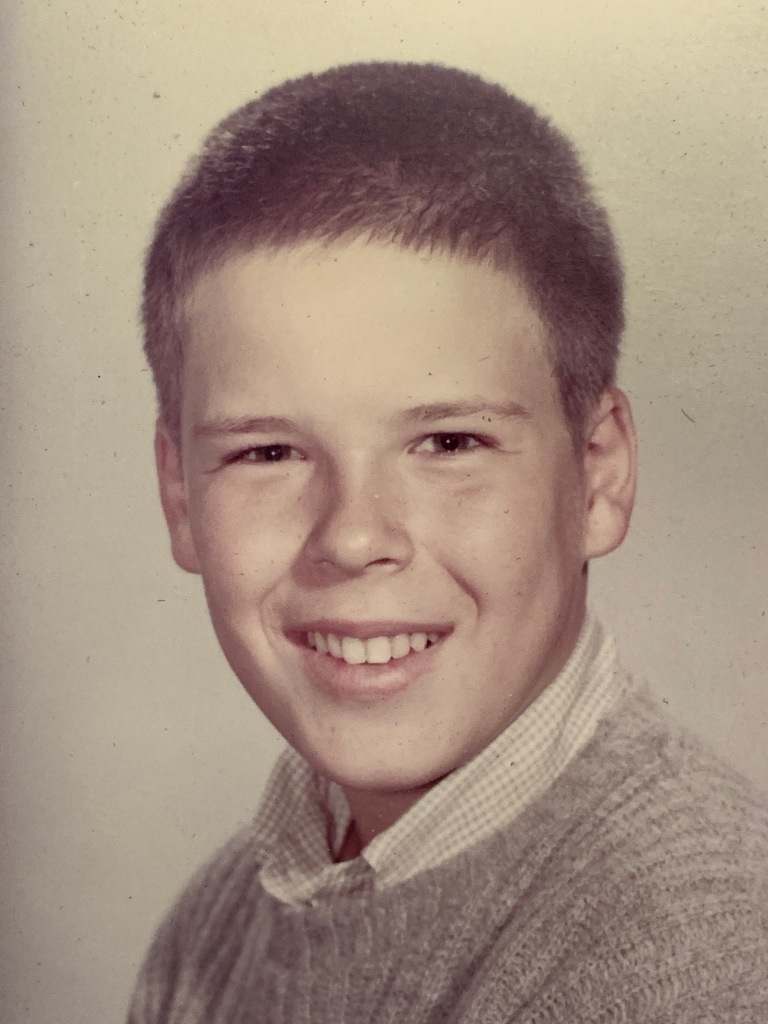

It was a great ride and a popular neighborhood attraction for several summers in the mid 1960s. Doom was clever that way. We were in those awkward, junior high, pre-driver’s license days of our lives. The long hot days of summer could get boring and a bit of boredom could quickly lead to trouble if we weren’t kept busy.

What our generation has done to keep kids busy is buy big TVs and gaming systems. Doom didn’t have those options. When we lived in upstate New York, he built a skating rink in the back yard and a baseball diamond in the field beyond that. In Connecticut, the climate was that much warmer and couldn’t sustain a rink. Nor was there space for a ball diamond. So in addition to a full array of bikes, sleds and a basketball and tether ball court, Doom came up with the monkey swing.

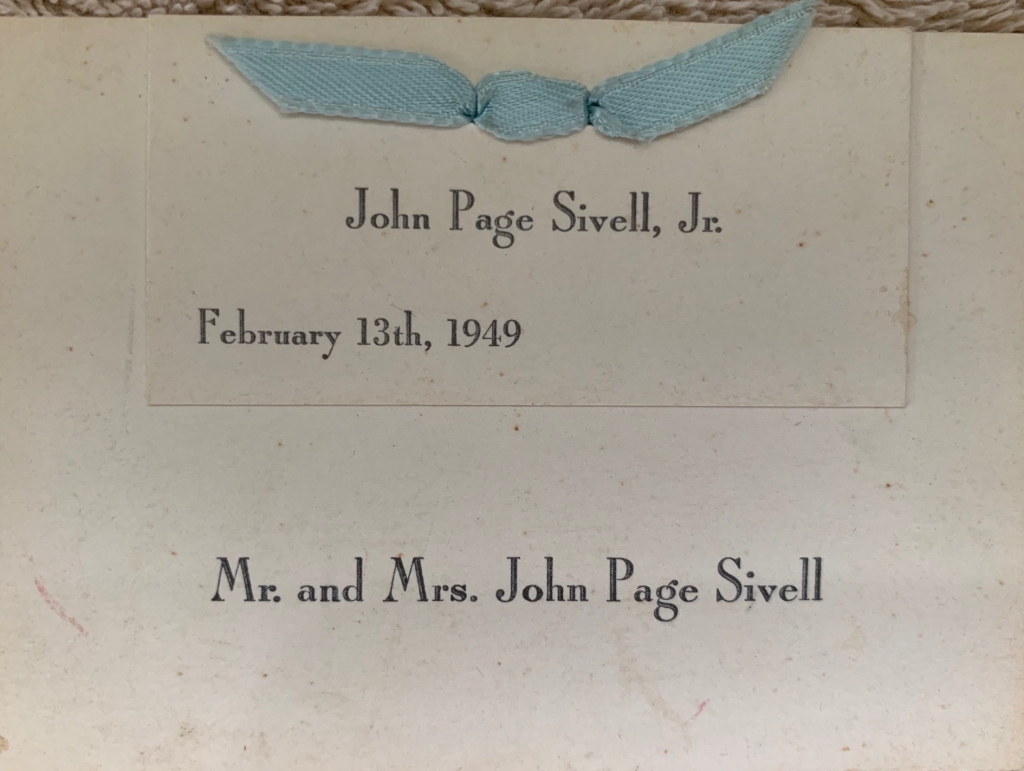

One mid-summer day, a couple of my friends and I had been swinging on the swing for a couple of hours, when Page showed up, casually munching on a hard roll. This got our attention. A hard roll was a treat. If you had an extra 25 cents after school, you could go over to Vanderbilt Drug Store, sit at the counter and have a buttered hard roll and vanilla coke. The drinks came in cone-shaped paper cups with metal bottoms, with a squirt of vanilla and cola syrup then mixed with soda water. Page was offering us this freshly baked treat for a mere 5 cents. He didn’t have any butter or soda, but it was still a pretty good deal. When we agreed to his price, he brought out a box of a dozen rolls and we ate until we couldn’t eat any more rolls.

A couple of days later, Page showed up with more rolls and a bonus: two dozen donuts. This is great, we thought. Swinging out of a tree and eating donuts. Summer couldn’t get any better for 7th graders. But I was suspicious. Later that night, after some badgering, Page told me where he was getting them.

“I find them in front of Vanderbilt Drug,” he said.

“You what?”

“Don’t worry about it,” he said, trying to reassure me. “They leave big boxes of the rolls and donuts out there every day. Compared to what they leave, I don’t take much. They’re not going to miss anything. ”

We both had morning paper routes at the time. My pick-up point was right near the drug store. Page’s was farther down Farmington Avenue, past the store. One morning, he told me, as he was pedaling to get his papers, he saw a delivery truck dropping off the baked goods for the store. So he stopped as the truck drove off and just watched the box.

No one came.

And it would be an hour before the store opened. Page began timing his trip to his paper route with the delivery of the baked goods. He’d take a donut or hard roll for his ride. This went on for a month. Then he got the bright idea that he could take larger quantities of the rolls and sell them.

“I won’t get caught.”

For a guy who got caught as much as he did, I still wonder why he always said that and truly seemed to believe it. Maybe it was the percentage of times he did stuff vs. the times he got caught. I didn’t care. I didn’t like getting caught even once.

Page was wrong about the owners of the drug store not noticing. He didn’t steal much at first, but when whole boxes of baked goods were missing from the morning delivery, the folks at Vanderbilt Drug Store noticed. One morning I went in to get the newspapers for my route at Mrs. Carney’s garage and she wanted to know if I knew anything about things getting stolen at Vanderbilt’s. She lived about 6 houses down a side street from the drug store and had about a dozen teen-age boys picking up their papers at her garage, so I am sure it seemed an obvious spot to find a suspect. The cops had stopped by and asked her to question us.

I didn’t usually see Mrs. Carney. At least, I tried not to. She had a stereotypical 1960s Catholic family with enough children for a full scrimmage basketball game and this job of having the bundled papers dropped off at her house and her counting out the papers for all the carriers probably was a nice little bit of extra money to keep the household going. But nobody looks good at 5 a.m. and when you were as tired as Mrs. Carney was and as stern as she had to be controlling all those kids, you looked positively frightening to a teenager.

I told her adamantly that I knew nothing about whatever she was talking about, like teenagers do when they most certainly do know what you are talking about. When I got home, I told Page that people were getting suspicious and he’d better knock it off. He did, for a few days. But he could never completely control himself.

The next weekend, I had a friend spending the night and Page went to work on us. He told us it would be a great score for a Saturday. All the kids in the neighborhood would be coming over for the monkey swing and we could make good money selling the rolls. I kept arguing against it. He wasn’t going to convince me. I was too scared to do something like that in the first place.

Not only had Mrs. Carney questioned me, but a few mornings after that, at 5 a.m., a guy dressed in dark clothes suddenly appeared out of the shadows in front of me. He wanted to know what I was doing – he apparently missed the big bundle of newspapers in the baskets of my Raleigh or he ignored them. He asked if I had seen anyone suspicious lurking around the drug store over the last few weeks. Well, I thought, I’ve got someone suspicious living across the hall from me at home. But I said no.

I kept telling Page that he had to quit while he was ahead.

He didn’t. He convinced my overnight guest, Rich Yulio, to go along with him on his paper route the next morning. I knew that meant a stop at the drug store. Yulio and all my other friends were afraid of Page – and fascinated by him. He was their Errol Flynn, their Edward G. Robinson. The swashbuckler. The gangster. And they wanted to be as cool or as teen-age tough as he was. And he knew it.

So while my friends came to visit the safe Sivell, they wanted to hang around with the dangerous Sivell. And if he were bored, he would permit that, all the while devising ways to get us in trouble – like jumping the fence at the cloistered monastery, racing across the large open field to the front door to bang on it and then trying to make it back to the 10 foot tall, wrought iron, spiked fence and over it before the sisters could summon any spirits to catch us.

When we would get in trouble – try getting over a spiked fence unharmed with nuns whacking you with brooms – he stood back and laughed.

So the three of us left the house early that morning and headed up to Farmington Avenue, took a left and pedaled the two blocks to Whiting Lane. We stopped for a few minutes while I begged them not to do anything. I wanted Rich to come with me but Rich was kind of a soft kid who desperately needed a harder reputation. He wanted to be seen as a bad ass. He was thrilled to be hanging out with my brother and to him, it seemed as if my brother liked him. But I had seen this all before with other kids and even with myself in that role.

Page just needed a bag man. Somebody to roll with and he didn’t care who it was. Whoever was around at the time was whom he would choose. So Rich stayed with my brother and supposedly they were heading off to deliver his papers. One last time I asked Page to leave the hard rolls and donuts alone.

“OK, you win,” he said, finally. “Go get your papers. We’ll meet you back at the house.”

“You’re just going to do your papers and then come home?” I was asking for reassurance from a guy who was going to do whatever he damn well pleased.

“I am going to do my papers and then go home,” he said.

I noticed that he left out the word “just” and that opened up possibilities for mischief but I had done what I could. So I went on down the street to Mrs. Carney’s and got my papers. Luckily, I got there earlier than Mrs. Carney. I didn’t want to see her, especially when she came out of the house chomping on saltines with the crumbs spilling out her mouth. I didn’t want to make small talk.

I quickly counted my papers and headed up the half block toward Farmington Ave. It’s the main thoroughfare through town and was usually dimly lit and quiet at that hour, but this morning it looked like Las Vegas: red lights spinning, search lights blazing. As I pedaled closer, I could see three cruisers and about 10 cops milling about the parking lot of Vanderbilt Drug. I stopped my bike in the shadows and watched.

I could see Rich in the back seat of one of the cruisers. The light inside the car was on and he looked petrified. I had just seen him five minutes ago and he was all pumped because he was Page’s new best friend. He had been projecting a new, harder edge. Now he looked like the pudgy, soft 7th grader that he was.

Then I heard one of the police radios squawk and a cop said they had just nabbed the other guy. About a minute later, a cop car came roaring down Farmington Avenue at about 60 mph from the direction of Page’s paper route. The light was on in the car and I could clearly see Page in the back seat and his bike sticking out of the trunk. He wasn’t defeated like most kids would have been. He had a half-smile that said, well, you got me this time. He pretended not to see me.

By this time I had moved out of the shadows and inched closer to gawk. But the cops didn’t care about me. They had solved the case of the hard roll thieves.

I don’t remember what Page’s punishment was. But I was glad I resisted his entreaties to the crime of the year in our neighborhood. I decided I was no longer going to allow him to talk me into doing things. Because the fact was, even though he may have gotten away with a lot, he got caught a lot. And it was only going to be a matter of time before it added up to some significant punishment.

I know my parents hoped he would outgrow this and begin to behave the way their other kids did and the way he was taught. But he wasn’t going in the right direction.

Next week: The Italian Influence

Categories: My story