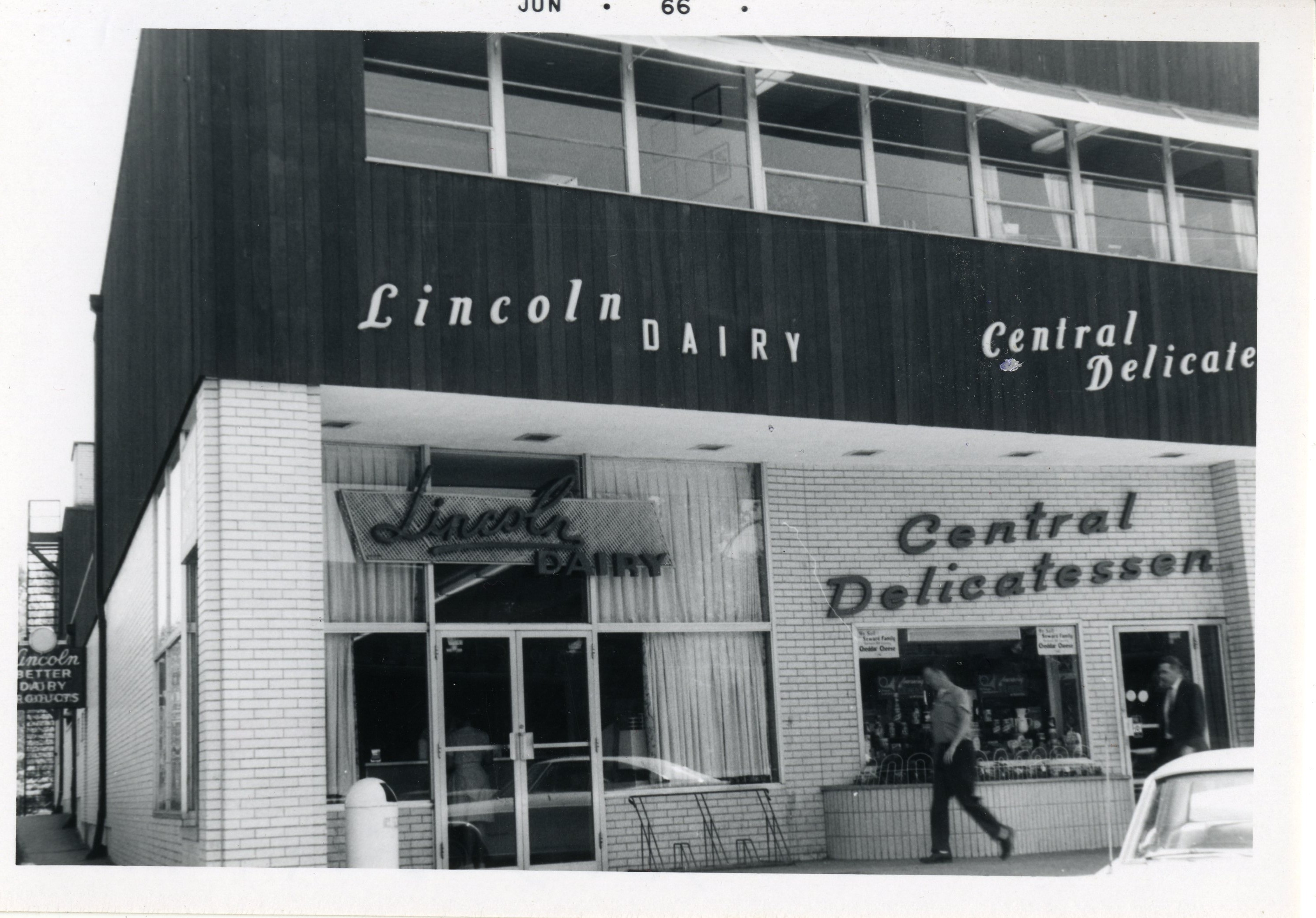

I got the job at Lincoln Dairy through Page. It paid much more than the paper route so I didn’t mind starting on my 16th birthday. On the other hand, I really didn’t want to give the route up. It had been my identity for four years and it was April, the best time to deliver papers. The moist, spring air captured the fragrance of the season and held it in place overnight before the winds of human activity dispersed it.

But with school, baseball practice and now the Dairy, I finally had to let it go.

It took me more than a month to find an adequate replacement. I didn’t want to leave my customers with just anybody. They had become accustomed to excellence. I was only late once and that was because of Page and the hard rolls.

Learning how to work a real job with co-workers, a direct supervisor and minute by minute expectations was a lot of work, but it was fun because we had a dozen part-timers from several different high schools. Racing to meet the expectations of lunch and dinner rushes, we worked as a team and and became friends, for the most part.

We did have a few older, full-time co-workers.

Louie, who was from Puerto Rico, did dishes in the morning and worked the grill at breakfast and lunch, working the 6 a.m. – 2 p.m. shift Mon – Friday. His accent was so strong, we couldn’t understand him. Since he always seemed to have a smile on his face, we would just laugh with him knowingly whenever he spoke to us. At the end of his shift, he’d hop on a bus out front headed for home in the city.

Georgie, the ex-con, worked the sandwich board from 7-3. He was also hard to understand but that was because he had no front teeth. We listened intently to his stories and would nod agreeably as if we had understood everything because Georgie would buy beer for us. Not only did we have to listen to his stories and laugh at the meandering punch lines, one or more of the girls had to flirt with him so he’d think that one glorious day, he might have a chance with them. Never mind that he was 5’ 4” weighed about 115 pounds and slicked down his hair with what looked like the same stuff we fried the fish dinners in.

Katty, the only full-time waitress who worked that day shift, was in her mid-fifties. She had the personality and build of a fire hydrant: short, stout and hard. She was agreeable when we bussed her section or brought food out for her. But disagreeable when we bussed her tables before she collected her tips. This was her full-time job and she wasn’t about to lose a dime to some rich high school kid. It was a affluent suburb, but the kids working at the Dairy were not children of affluence.

John was the genial store manager who was a father figure to the teens and bail bondsman for the rest of the help.

Duane, the assistant manager, was no longer a kid at 24 but wasn’t yet a full-fledged adult, and thus was confused in his role. His shift started when John and the other full-timers left. He spent his workday supervising the high school and college kids who were working their first real jobs. Most needed a lot of supervision. But Duane didn’t know whether to yell at or conspire with us. He eventually took on the demeanor of a mall security cop.

As my brother got more experience, he got more responsibility and the manager would let Duane leave early and allow Page to close up. I thought that was amazing. Little did I know that within a year, I’d have my own set of keys and would be opening on Sunday mornings. It wasn’t Tiffany’s with diamonds and gold. It was Lincoln Dairy. Burgers and ice cream. But still.

When Page was in charge, we worked hard. But when the store was closed and our work was done, we would have parties in the basement. That basement ran the entire length of the store, several thousand square feet. We’d bring a radio down and have dances amidst the boxes of napkins, straws, coffee filters and soda syrup canisters.

The Doors had just burst on the scene and “Light My Fire” was on the radio constantly. I listened with earnestness as the cutest waitress – who was a college woman, attending Eastern Connecticut College (which I had never heard of before) – marveled at the lyrics as the band came out of the break on the extended version of the song: “Now the time to hesitate is through,” Jim Morrison sang. That was so cool, she said. I had to agree. After all, she was in college and knew things.

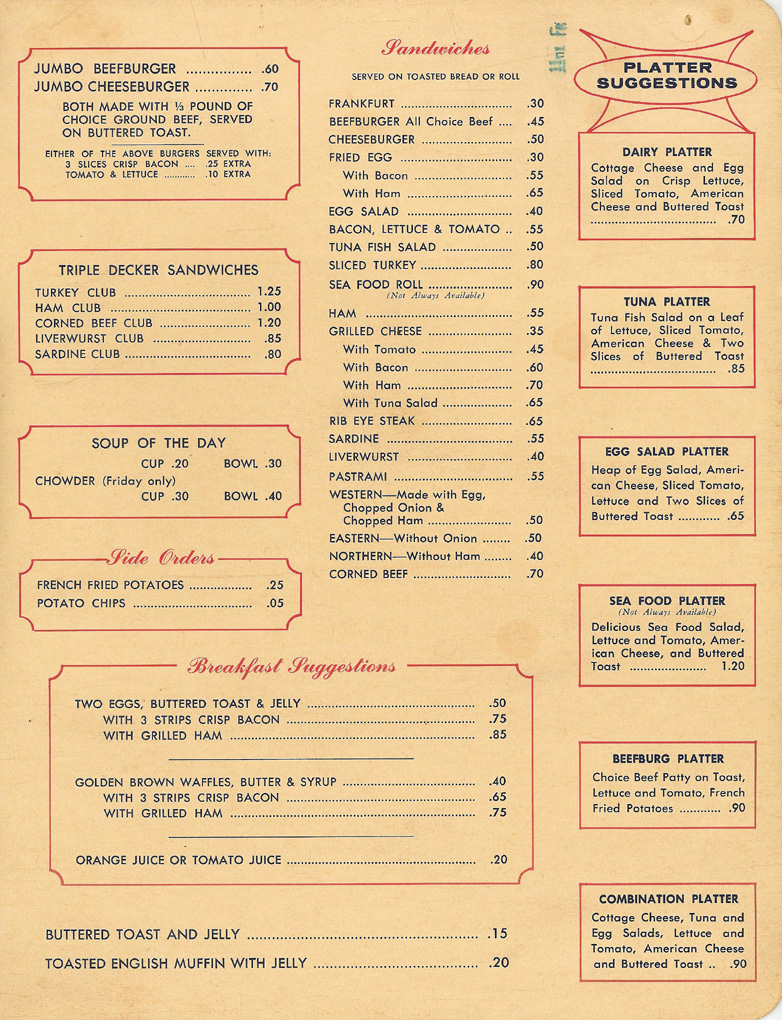

At first, my job was to bus dishes and wash them. Once in awhile, I would help if we got busy by bringing food to people, but I didn’t like that very much. I also learned to work up front. There was a small parking lot right in front so people could make a quick, convenient stop on their way home from work.

We sold a lot of milk and dairy products and I got to be very good at working the cash register and adding things in my head.

We also scooped a lot of ice cream. That was what we were known for. We scooped so much, toward the end of summer, several of us had tennis elbow.

We had some competition from the Farm Shoppe on the other side of the Center, although it was a bit higher end. Our advantage was that we were local and they were not. Everyone knew where our main plant was on New Britain Avenue so they knew the ice cream was fresh.

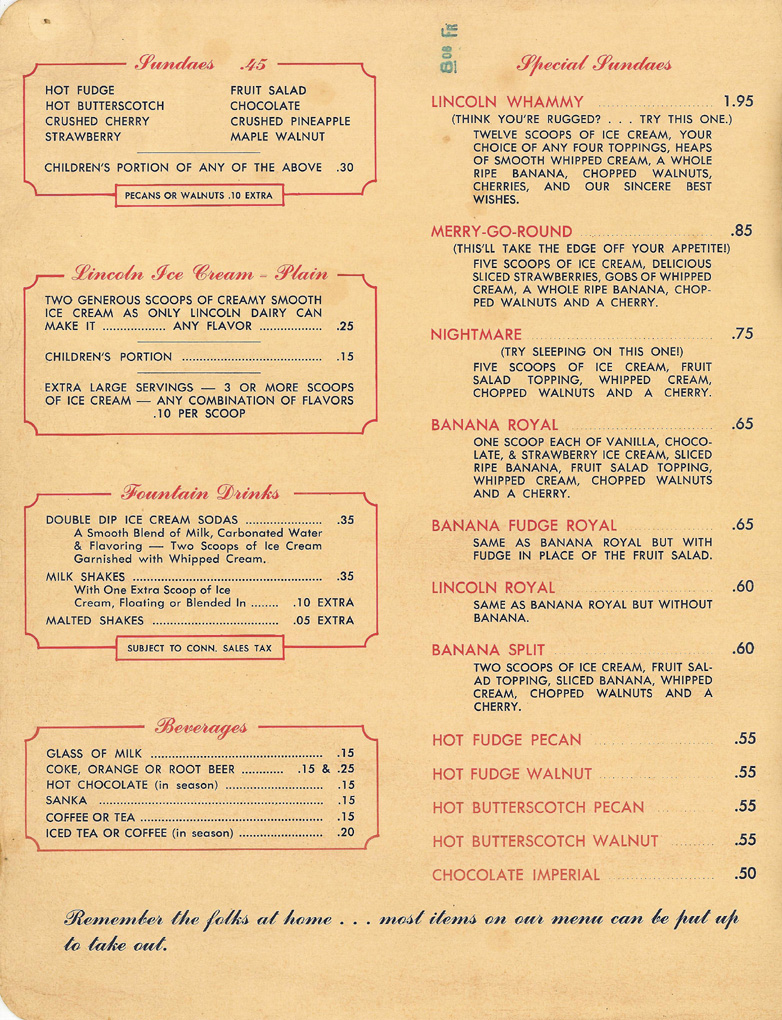

Page was in charge of the shift on my first day and while I was listening to his instructions, I was distracted. After all, I was behind the counter and within reach of more than a dozen varieties of ice cream and multiple toppings. After we closed for the night, Page said as soon as I finished washing the dishes and cleaning up, I could make my own sundae.

Wow. Getting to touch the equipment that only the experienced workers got to touch. Equipment I’d been staring at since I was a little kid, dreaming of one day leaping over the counter and playing in that amusement park of sweets.

You had to work at the Dairy for a few weeks and sometimes months and be able to do the simplest job proficiently before you got assigned another job. And I knew this might be my one chance to scoop any ice cream or ladle hot fudge if I didn’t measure up. Certainly this opportunity wouldn’t happen on someone else’s shift.

Page said I could make anything I wanted. I got the biggest bowl, the one for banana splits, and loaded it with ice cream. Then the toppings. I loved hot fudge. That went on. Butterscotch was also a favorite. So a scoop of that. Strawberries were next. They were expensive and we didn’t always have them at home. Maple syrup was too much to pass up.

It was topped with whipped cream, a Lincoln Dairy specialty. We whipped our cream every day, several times a day. We had a machine that burped air into the cream from the bottom of the bowl. We’d add some simple syrup and start whipping with a big whisk. It wasn’t difficult although it took time and we always seemed to run low just as a couple of little league teams crowded into the booths. But people really liked that it didn’t come out of a can.

With the whipped cream the finishing touch, I began to eat. Strange, I thought, even with all these wondrous ingredients, it doesn’t taste very good. But I kept eating as if I had discovered a new taste sensation. Page could tell what I was thinking.

“Not very good, is it?”

“Are you kidding,” I bluffed. “This is the best sundae I’ve ever had.”

“Well, you haven’t had very many sundaes then,” Page said. “Everybody does what you just did when they get their first opportunity at the fountain. But some stuff just doesn’t go with other stuff, even if it is all sweet stuff.”

He came over and put his hand on my dish.

“Want any more?”

I shook my head.

“You just learned a very valuable Lincoln Dairy lesson,” he said, sounding very grownup as he scraped the glop from the bowl to the garbage. “Our sundaes have specific recipes, kind of like Mom’s lasagna. Stick to the recipes. There’s a reason we have them.”

I worked hard and the store manager and the assistant began to trust me as they trusted Page and I’d occasionally be left in charge. Not to close or open, but the managers felt they could leave the store for a few hours while I was there.

Once, when I was in charge and scooping ice cream at the front counter, some junior high kids, after they got their cones, were goofing off and annoying customers. Kind of like my friends and I would have done at that age. It escalated a bit and I finally told the kids to go outside. They stayed out in front of the store laughing and, I soon realized, plotting. One of them suddenly smeared what was left of his ice cream cone all over the front window and all three began to race up Farmington Avenue.

I was behind a horse shoe-shaped counter so I had to go back around the counter before I could go forward. But I gave chase. I was out of that store as fast as I could go. I soon had them in sight. I was focused. I couldn’t see anything but them. I even think I was beginning to gain on them a bit. Then they split up. The three of them took off in different directions and I had to choose which to follow. So I chose the one who had tossed the ice cream. Unfortunately, he was the fastest and he was faster than I was.

As he pulled away, I realized I was a good 6 blocks from the store I was in charge of. My thoughts slowed me down and the kid faded into the distance. The rage that had propelled me was gone.

The rage turned to embarrassment. After all, I was in my Lincoln Dairy uniform, a very bleached and very starched white shirt and white pants with a burger grease and chocolate ice cream-stained apron, running up the main street in a very posh town.

I stopped and began the long walk back to the store. By the time I got back, one of the waitresses was just finishing cleaning the window and it was busy in the store and I got right back to work and mostly forgot about the incident. Until I called Bethani for our nightly talk.

She was mad and wanted to know if I wanted to break up.

“What the heck are you talking about?”

“Well,” she said, “you ran right past me this afternoon and didn’t stop to say hello or acknowledge me.”

She had been with her best friend, Mary Montanya, and they were heading to the Dairy to see me. She saw me running up the street – apparently hadn’t seen the kid I was chasing – and assumed I was running toward her. But I was so focused on the chase that I had run right past them. I tried to convince her what was going on and that I hadn’t seen her – truly – but it took a couple of weeks to win back her trust. Which should have given me a clue as to where the relationship was going.

Another time Bethani came in to the store and I did see her so I made her an ice cream cone. When she tried to pay, I refused her money. That’s one of the things the store owners in the Center really worried about with so many teens working there. They knew we’d be serving our friends and the profits could go out the window. I followed the store rules pretty strictly, but this was my girlfriend so I waved off her attempt to pay.

I didn’t see a woman standing at the other side of the counter who was closely watching what I had done. When I turned to help her, she wanted to know if that girl had paid. I didn’t know who this lady was, but luckily, I didn’t give her my usual wise guy answer like it was none of her business. I was in customer service mode. I told her that I was going to put it on my employee bill because she was my girl friend and I got a 10 percent discount. She seemed to buy that.

I was lucky that she did because she turned out to be the wife of the Dairy’s general manager and she said her household income and her husband’s bonus depended on honest teen-age clerks. But she didn’t buy the answer enough that she didn’t mention it to the manager and tell him to keep an eye on me. That was fair enough, I guess. I’m glad I learned that lesson early on.

I made $1.25 an hour. The paycheck for the full week’s work from those days came out to about a dollar an hour after taxes. But I felt like I was loaded. I worked at Lincoln Dairy throughout high school. I wasn’t allowed to work school nights because my grades were so bad. Mostly on weekends. During football season, I only worked Sundays – all day – and made enough to put gas in my car and take Bethani to a movie or a dance.

Page and I didn’t work together often, but when our shifts overlapped, we worked well together. It was good for Page to meet girls at the Dairy because it wasn’t a party situation. He had to get to know them through their work ethic and he developed friendships with some of them. There were a couple of college girls that treated him like he needed some reforming and he took to it a bit. They treated me like their kid brother.

But for Page, friendship with a girl or going steady with one was not enough. He liked action and he attracted girls who wanted what he wanted. And that often led us to the Sleepy Hollow Motel down on the Berlin Turnpike.

It was the kind of motel where traveling salesman selling cheap products out of cardboard suitcases stayed. Several of us would pool our money and rent a couple of rooms.

The beds were so swayed, they looked like hammocks. And for 25 cents, you could get them to vibrate for 5 minutes. We always got a couple of rooms, everybody pitching in a couple of bucks. One room was the general party room and the other room was for more private matters. Page was very proud of the night he had 2 girls in the other room and described to me later in great detail how he jumped from bed to bed and back again.

But by May of that year, Bethani and I were spending a lot of time together. I stopped going to the motel parties, stopped going out drinking with Page. I didn’t stop drinking completely, but I did it in a more mature way – for a 16 year old at least, in a not-in-danger-of-going-to-rehab kind of way. I wanted to hold on to my girl friend and I wanted to hold on to my money.

The summer went by pretty quick. I finally had about 500 dollars to spend on a car. I had been saving my paper route money and then the Dairy money. Doom helped me look and it came down to two 1962 Oldsmobile F-85s.

A tall, thin shirtless guy in his late 20s, who came to the door with a 3-year-old tugging at his pants, had one with about 33,000 miles, bucket seats, a custom two-tone paint job – aquamarine on the bottom and cream on top – and three-speed on the floor. It was cool. He seemed reluctant to have to give the car up.

The other option featured dull, white paint, three-on-the-column shifter, bench seats and 67,000 miles on the odometer. Owned by a little old lady who said she only drove it to church. Although, I thought, with that mileage, she either went to church a lot or her congregation was in New Hampshire.

The cars were the same price but Doom thought the old lady’s car would be better because she wasn’t a hot rodder. Maybe he was right. But I had a lot of trouble with that car. And since I didn’t know anything about cars and neither did Doom, I had to learn on my own or get one of the greasers at school, as we’d referred to gearheads behind their backs, to help.

I didn’t get my license right away at 16. You got a discount if you took driver’s ed in school so I signed up to take it during the summer. I’d go to work at Lincoln Dairy – I was filling in for Louie the fry cook – and work the 6-2 shift. Except for those few weeks of driver’s ed when I would skip out at 9 and beat it down to the high school for an hour.

During this time, my car just sat in the driveway. It was a temptation too big not to take and Page and I would go joy riding when Mom and Doom weren’t around. One time we drove around the Center and pulled up at the store where Bethani was working. She thought it was cool on one level but very bad on another. Page looked at his watch and said we’d better get home before Mom and Doom got home.

We drove back down Farmington and turned right on Beverly. As we approached our house going down the street, we could see a very familiar car coming up the far end of the street. Doom’s company cars always seemed to be large, yellow, Plymouth station wagons. It was hard to miss a car that big and that yellow. Page put the pedal down and we peeled into the driveway, jumped out of the car and dove into the backyard. We tried to look as casual as we could, pretending to have just finished an exhausting game of tetherball when Mom and Doom pulled in a minute later. They never said a thing to us. And at the time and for years afterwards, I thought about how we had narrowly escaped and had fooled them. Now that I am a parent I realize, they probably weren’t fooled. They were not stupid people. They just didn’t want the confrontation.

A few months later, after I was licensed to drive the car, I had to dive into the yard again.

Some guy on a motorcycle was tailgating me and I gave him the finger as I tended to freely do when I first got my license. It takes a few years – a lifetime for some folks – to learn to treat fellow drivers with the same courtesy you would a fellow pedestrian. So I was flashing my finger around like a 16 year old does. But I flashed it to the wrong guy. And he followed my all the way down Farmington Ave.

No matter how fast I tried to go, I couldn’t shake him. I tried slowing at lights until they were about to change and then I’d charge through them, hoping he’d get stuck. But whatever I went through, he went through. It was a bit like the movie Duel – the guy was on me and wasn’t going to let go. When I got to Beverly Road, I didn’t signal. I waited until I was almost past the street and then turned very suddenly, sped down the street and pulled into the driveway and dove out of the car and barely made it into the house in front of this guy. He began pounding on the door and Mom had to go out and calm him down.

That wasn’t too uncommon in those days. I was a bit of a hot head. And I did a few stupid things. One time I was at a friend’s house and I was fooling around about letting him get in the car. Suddenly lurching forward as he tried to get in. One of the neighbors saw us, wrote down my plate, called the DMV found out who owned the car – my mother was the co-owner – and the lady called our house. So when I got home, my mother let me know that a car is not a toy and I lost it for a week. I was pretty upset at the time, but I learned a lesson. And I don’t think it was to behave, at least, not right away. I was just a bit more careful and tried to pay attention to see who was around when I was doing stupid stuff.

1967 has gone down in history as the Summer of Love. I wasn’t getting that kind of love, but I was in love for the first time. Bethani and I would go to our jobs in the Center – which is where everyone wanted to work because that is where the action was. When we were younger, we’d all spend our Saturdays walking around the Center. Now we were getting paid to be there.

Page seemed to be doing well in his 10 months of freedom. He was working 40+ hours a week at the Dairy. He was hanging out with some new friends from the other side of town that my parents weren’t quite sure of and there were daily calls from multiple girls, but there were no visits from the police. Just compliments from his boss at work.

Bethani and I went to the weekly dances at the high school in the town Center. Everybody looked forward to them as it gave you a chance to keep in touch with your school friends that you didn’t get to see on a daily basis. And having someone to go with and not have my stomach in knots about asking someone to dance made them fun for the first time.

My plans were to quit working full-time hours in early August and go to Martha’s Vineyard with the family of a good friend. It was a great summer.

But then the phone rang.

Next week: Chapter 12: Page’s Accident.

Categories: My story

Audio quality is much better than when you started. Have you about using Sound Cloud instead of the Word Press default player? It looks cooler and I think sounds a bit better. Like so many plug ins, there’s a free version with different paid options.

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/soundcloud-music-audio/id336353151

Cliff, you know I always follow your advice. I will check it out.

I just binged and read 6 chapters to get caught up and I am loving this Mr. Sivell! I have so much to say! Your writing is so clever and I can hear you when I read it, which I love! I have everything already painted in my mind, your town, your childhood home, your school, your job, feels like I was there! Also a telltale sign of some great writing. I am absolutely loving it, especially loved the chapters of your parents, very special stuff there, can feel your love for them through the writing. I am so appreciating this look into a time that I so much appreciate but never experienced, especially through the lens of someone I very much respect and look up to and has so many incredible stories and life experiences! I feel cool just even knowing the writer 🙂

Aly: Thanks so much for that WONDERFUL comment. It’s a real boost of confidence. I was hoping some people my age might see the universality of my stories and reflect on their pasts. But I didn’t just want to talk to old people 😉 . I’m very pleased (!!!) that I am able to provide a window on that time for you and that you are able to SEE it.

Alan, Very much enjoyed your podcast. As a neighbor from Beverly Rd and teammate at Hall your writing brought back memories that

made me think it was yesterday.

By the way, I’m pretty sure Benny had 6 long

hairs on his nose.