Senior year, I lost a fight to a guy on crutches.

And it’s worse than it sounds.

He wasn’t even standing during the fight. I was.

It started because I was in charge of the student lounge, previously an unused, first-floor classroom on the science wing which became a place where students could escape school without leaving school.

Until our senior year, school was pretty prescriptive. Once you walked onto the grounds, you were either in class, at lunch or in study hall. If you were in the hallways at any time other than between classes, you needed a pass. There were even student guards – hall monitors – who could demand to see your pass.

Needless to say, we chafed at this and looked for ways around the system. This was the 60s, after all. We were fighting the man. Sometimes we’d would steal a pad of passes from a teacher’s desk and forge their signature. Or better yet, we’d steal them from the efficient teachers who had signed the passes ahead of time. If you distracted those teachers, your partner-in-crime could rip a couple of the passes off the stack and you had authentic currency to move freely about the school.

But a new day dawned our senior year. SSP. The self-supervision program. We no longer had to forge our names or steal passes.

If you qualified for SSP, you got a badge and you were allowed to go wherever you wanted to go when not in class. The hall monitors lost their power over us. You could go to the library. You could go outside. Or you could walk two minutes to the town center and spend your 48 minute free period drinking coffee, eating donuts or smoking cigarettes or all three rather than daydreaming in the cafeteria study hall with 75 other kids.

But not everyone qualified for that freedom.

You could get an SSP badge if you were on student council, elected out of your homeroom. That wasn’t going to happen for me because after three years with the same students and my smart mouth, I was not universally revered by the 30 kids in my homeroom.

Or you could get one if you had to a high grade point average and good citizenship grades. I had neither of those. But I did have a friend in a high place. The president of the school, John Abraham.

John appointed me to his “cabinet,” making me in charge of the student lounge, another option for our new found free time. That gave me all the privileges that all the other members of the student council and the students with good grades and good citizenship had earned.

It could have been the stereotypical political do-nothing job. I just had to be in charge of the room. Whatever that meant. I didn’t have to clean it. It was simply an extra classroom that the school had given us to use between classes. The idea was that if you didn’t want to go to the library, outside or to the Center, you came to the lounge. The administration wanted to grant a bit of freedom, but they didn’t want students wandering the halls.

I didn’t really have to do anything but at the beginning of the year, I had enthusiasm. I decided to act as if I had campaigned for the position: I was going to get furniture, vending machines and a rug for the lounge.

I got Walt, the head janitor, to take me down to the bowels of the school where he let me have my pick of some ancient furniture that was last used in the teacher’s lounge just after the war.

Dr. Dunn didn’t say no to the vending machines because he didn’t think he had to. He figured it would take me forever to figure out whom I needed to call. And when I did make contact, they would want a deposit. And even if I had managed to come up with that, Dr. Dunn was going to stall on the install. But by late fall, we had a candy machine.

Getting the rug was easier. Doom’s company was now selling rugs for office buildings. So I figured we would get a good deal and Dr. Dunn was OK with that. The only problem was that I was the one measuring for the carpet.

That was a mistake.

The day the carpet showed up, so did the bill. Dr. Dunn called me out of physics class. Normally, he was a pretty mild-mannered guy, even when he was upset. He was not a yeller, like Coach Chalmers. He talked to you out of concern. But when I got to his office that day, he was waving the bill at me and his face was red.

“This bill is twice the price you told me it would be!”

Really? How could that be.

“Maybe it’s because you ordered twice the rug!”

He marched me down the hall to check on the workmen as they finished installing the carpet. It was easy to see there was enough carpet to cover the lounge and the room next door and with some probably left over after that.

Dr. Dunn was mad and disappointed. I couldn’t decide which bothered me more. He decided to leave the extra roll of carpet in the lounge leaning against the wall so I could see it every time I went in there. And so could all the other kids.

“What’s up with this extra carpet?” they would ask.

“Shut up,” I would answer.

Dr. Dunn never outed me. But he let me sweat for awhile. A few weeks later he told me to get rid of the carpet.

“I don’t care what you do with it. Just get it out of here.”

So I took it home and Doom installed it in my room on the third floor.

I learned a lesson. These days, I measure three times. Then four. And still, more times than not, I get it wrong.

The lounge proved popular, especially on rainy days and throughout the winter. It was a much better place to be than study hall. Unless you wanted to study.

I surprised myself about how serious I was about the lounge and my job. I viewed it as MY lounge and I was determined to protect it, despite there not being much to protect.

On the day of the fight, the lounge was crowded, with a half dozen clusters of kids. They were spread out all over the room, some stretched out on the furniture and others sitting on the newly-carpeted floor. Some were simply socializing, while others worked on school projects and a very few, on homework. I was pleased the lounge had become a happening spot.

Then I saw Bob sitting on the arm of a couch and my mood changed.

I had been raised in a house where we never sat on the arm of a piece of furniture. So I told Bob that the arm is not a place for sitting and that he needed to sit on the seat of the couch. Despite being my best friend, he said no. You don’t tell me what to do. And he said it loud enough and with enough defiance that the buzz of conversation in the room suddenly stopped.

It was a challenge to my authority and my lounge that I could not ignore. And since we were best friends and everyone knew it, there was added interest in this argument. It had the potential to be more interesting than any homework or weekend plans they had been previously talking about. Everyone’s attention turned to the corner of the room where I stood above Bob as the argument escalated. I got madder and madder as Bob refused to get off the arm of that rickety couch.

I didn’t care that he was on crutches. I didn’t care that he had broken his leg skiing a month before. I finally had had it. My words had failed me so I did a quick calculation. This might be my only chance to beat Bob up. I generally had a pretty good idea of which fight I might win – not many – and which I likely would lose – most of them. I figured with Bob in his condition, the odds had tipped in my favor.

So I took a swing at him.

There was no way I should have missed a sitting target. Yet I did.

I was so mad, I swung wildly. And because of my wild swing, I stumbled toward him like a drunk at closing time. That left me close enough to him so that he could easily punch me in the stomach without having to leave his perch. He knocked the wind out of me.

I lost a fight to a guy with a broken leg who never had to get off the arm of the couch.

Bob may have won the fight, but I was right about what his sitting on the arm of the couch would do. By the second semester, that particular arm that he was sitting on, on that particular couch, had fallen off. And the rest of the furniture looked as if it would be more at home in a dumpster than a student lounge.

Spring semester, I was busy at school and not because of schoolwork. Other teachers had begun to notice that I was good at organizing students. Other than Bob, they listened to me.

The Spanish teacher, Mrs. Freundel, got me to co-chair the American Field Service club. We raised money to help bring an exchange student to school every year. I helped organize and publicize a student workday and we set a record for most money raised.

In addition to organizing a school dance that raised money for the baseball team’s pitching machine, I was on the homecoming committee, helping plan the end of the year party.

And I had a social life. It drove my mother crazy every time I said yes to something because she was well aware of something I wasn’t: The academic work I didn’t do that year and the years before were going to hurt me when it was time to go to college.

I did have pretty solid SAT scores, the trip to Boys’ State, sports and the school service. And I wrote a good essay about why I played baseball left-handed (Doom gave me a left handed glove for my 6th birthday and I didn’t tell him it was for the wrong hand because I was afraid he’d take it back. So I became I left-hander. It’s the only thing I do left handed.).

Despite my guidance counselor having said that the only school that would have me would be the local community college because of its lack of admission standards, I got into 6 of the 7 schools I applied to. The problem was, the one school I really wanted to go to, the one school that might have saved me from myself during a disastrous freshman year, was the one that didn’t want me: Stonehill College, a small, Catholic school outside of Boston.

I desperately wanted to go to school in Boston. Not because of all the great academic institutions. But because of all the young people that attended the roughly 100 great academic institutions in the area. Still, I realized at that time I needed a structured environment to succeed, which is why Stonehill seemed like the perfect choice.

Doom and I spent a day touring a few schools in the Boston area and had an interview at Stonehill. Apparently, I was on the bubble and they wanted to get a measure of me. I didn’t prepare for the interview and so when talking to the admissions counselor, I mumbled monosyllabic responses to questions while slumped in my chair. I didn’t appear interested. Doom was really pissed off when we got back in the car. He knew that there was no way I was getting in there. He was right. They rejected me.

My friends went to Duke, Tufts, Harvard, John Carroll. Bethani was the #1 student and Sam was in the top 10% of the class. But I wasn’t focused on being a scholar. Even if I had been able to hear my parents admonishing me, pleading with me to work as hard on my grades as hard as I worked on my school and social lives, I am not sure I could have changed a thing.

One day in early Spring, Bob showed up at school with an ad he had clipped from the new music newspaper, Rolling Stone, that said 40 acts were going to appear at a three-day concert in August in the countryside of upstate New York, at a place called Woodstock. Free camping. Just bring coolers and sleeping bags. All for $18. It sounded great, but the price seemed pretty steep to a high school kid earning $1.60 an hour. The tickets alone would be two day’s wages.

Bob was really excited about it and said we HAD to go. I said I would think about it, kind of hoping he would forget about it. It seemed too big, too fantastic, too far away for it to really happen. After all, Bob had just turned 18 and I was still 17.

Then, Sam and I broke up. Or, she broke up with me. Right after the school year ended. There wasn’t a big fight. The relationship simply had run its course in the confined space of high school and that time of our lives. Again, I was not an ideal boyfriend. Even with my academic failures, I had an inflated sense of myself and was beginning to notice some other girls in town.

Sam definitely felt the distance increasing between us as we faced the gulf of life outside of West Hartford and she was starting to explore her options, too. She was very smart. And a babe, after all.

We had raced through the end of the year events together: prom, beach weekend and graduation. But a day or two after graduation, Sam said we should see other people as we were headed off to different colleges in the fall.

Normally, I would have fought to save the relationship on instinct (“Nobody breaks up with me!”), but since there was one girl in particular who kept coming into the Dairy to flirt, I accepted being dumped without an argument. After seeing each other almost every day that year, Sam and I saw each other only once in the next 10 years.

I pursued that girl from the Dairy but that didn’t work out nor did any other relationship that summer. Or for the next 12 years, for that matter.

After three years of my life wrapped up in high school and my friends there, graduation came, and overnight, I was no longer a part of it. The social scene was gone.

My summer job gave me a preview of what adult life might become: I got up, went to work, worked with a bunch of older, coarser guys who didn’t read and came home exhausted and often fell asleep at the dinner table.

The good part, I suppose, was that I was too tired to go out and there was no one to go out with so I saved money for school. And for that summer festival Bob kept talking about. He had already bought his tickets. He kept urging me to buy mine.

My job was unloading bundles of ceiling tile from boxcars, which I then loaded into a truck that I then would drive to various construction sites. Other days the load would be 4 X 8 foot slabs of sheetrock. Sheetrock days were the worst. Because not only did I have to unload the truck at the job site, I then had to distribute the boards to the carpenters installing them.

It wasn’t too bad at the start of a project becasue I only had to carry them to the first floor. But as the project moved to the 2nd floor and then the third, etc., the extra steps made the job progressively harder.

First of all, 4 X 8 sheets of anything are awkward. And these sheets were heavy, about 45 pounds. At first I could only carry one at a time. But that wasn’t fast enough for the installers because they’d always be waiting for me to bring the next sheet. So I had to carry two at a time.

And, since we were a non-union shop, the union electricians who controlled the elevators made me take the stairs. And the stairs to each floor had a switch back which I had to navigate carefully so as to not ding the corners of the easily damaged drywall.

It was a job Doom got me with some customers of his, acoustical contractors Genovese and Didonno. It may have been a lot of work, but it was a big pay hike, $2.50 an hour. I could earn a $100 a week!

The owners were pretty rough around the edges. They swore. A lot. Especially at me. But I’d been out of the house and knew that a lot of guys talked a lot differently than Doom.

They especially liked to swear around Doom, since they knew he didn’t. When he showed up for a sales call, the language at Genovese and Didonno got coarser than usual. Doom knew their game. But as long as he made a sale and could get to the golf course, he let them have their little fun.

I liked driving the big trucks, although I had no training. Genovese had just thrown me the keys one day and told me to gas it up. When I returned 15 minutes later, myself and the truck intact, he figured I had learned how to drive it.

It really wasn’t that difficult to operate, except you never knew when the brakes were going to catch. They were air brakes and if you simply stepped on them like you are in the habit of doing in every day driving, the pedal would go straight to the floor. You had to think ahead and begin to pump them before you planned to stop. But, the amount of pumping varied from stop to stop. Sometimes you needed to pump a little and sometimes a lot. Driving those trucks carried some risk.

One rainy morning I was heading to Stamford, Connecticut down I-95 with a full truck of tile. As I approached a tollbooth, I began the pumping process, except for the first time, the brakes didn’t need any pumping and they caught immediately. More accurately, they locked up and the truck went into a spin.

I didn’t close my eyes, but as the truck spun, I couldn’t focus on anything. I tensed up, waiting to get hit and die. It seemed like an eternity before it stopped. In my mind, the truck spun around at least twice. When it stopped, I was facing oncoming traffic. On I-95, one of the busiest stretches of road in the country.

Luckily it was about a half hour before full rush hour so cars had enough room to maneuver around me and there was just enough time to turn the thing around and head to the tollbooth. There was a cop sitting there, watching the whole thing. He didn’t move a muscle. I suppose I could have gotten a ticket for driving too fast for conditions. But I would have argued for giving a ticket to Genovese and DiDonno for making me drive the dangerous piece of crap.

On another delivery, I was working with one of the carpenter’s apprentices. Richie was very big and strong and had played a half season with the Hartford Knights, the local semi-pro football team. He favored sleeveless T-shirts, which exposed his massive arms. He was a nice guy, however not clever enough to ever become a full carpenter. But he had more stature on the job because he wasn’t a “college boy.” The more education you had in that type of job, the lower down the ladder you were.

That particular day, we had two job sites to deliver to. We didn’t know which site we were going to first, as no one was in the warehouse to tell us. We faced a dilemma. If we didn’t load the truck, we’d get yelled at for standing around on company time and not working. But if we loaded the truck out of order, there’d be a lot of extra work for us when we got to the job sites. So instead of loading the jobs front to back, we got the bright idea to load one job’s tile on the right side and the other on the left side.

Just as we finished loading, the boss showed up and told us which load to drop off first. So Richie climbed in behind the wheel and I hopped into the passenger seat and we drove to the first site and unloaded the left side and headed to the next site.

We were feeling pretty pleased with how smoothly the day was going as this was the first time we had loaded the truck without the boss’ supervision. And the boss had seemed pleased that we had taken the initiative to load the truck without being told. Which was ridiculous because how hard is it to load a truck? And our packing method had made it easy to unload without having to know the order of the stops for the day.

It was about that time that we had to get on the interstate. As we were accelerating on the curve of the ramp, we felt something funny, as if the truck was beginning to lift off the ground. And it was. On the driver’s side. Because like 2 idiots, we had left all the weight on one side of the truck. It took us only seconds to realize what was happening and I dove across the bench seat and practically sat on Richie’s lap in an effort to keep from flipping the truck.

It was more instinct than a plan as I was trying to keep from falling out the passenger window. Luckily, Richie remembered to pump the brakes, and the tires slammed back to earth. Once we stopped hyperventilating, we laughed. And rearranged the load. We didn’t tell the bosses about our brilliant loading strategy.

That job paid well, $2.50 an hour, about a dollar above minimum wage. But it was so physical and tedious that when Bob began talking more intensely about that music festival in New York, I started paying more attention, seeing it as a possible escape hatch.

We studied the acts scheduled to perform and it was mostly headliner after headliner: Richie Havens, Joan Baez, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Who, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix, Country Joe and the Fish, 10 Years After and John Sebastian.

There were some unknowns: Sweetwater. Melanie. Joe Cocker and his Grease Band. But we figured there were enough names to make the trip and money worth our while.

So we saved our money all summer, quit our jobs on August 14th and then got up early the next morning and started driving west in Bob’s mother’s 1969 yellow Mustang, on our way to our last chance for adventure before college. Woodstock.

Categories: My story

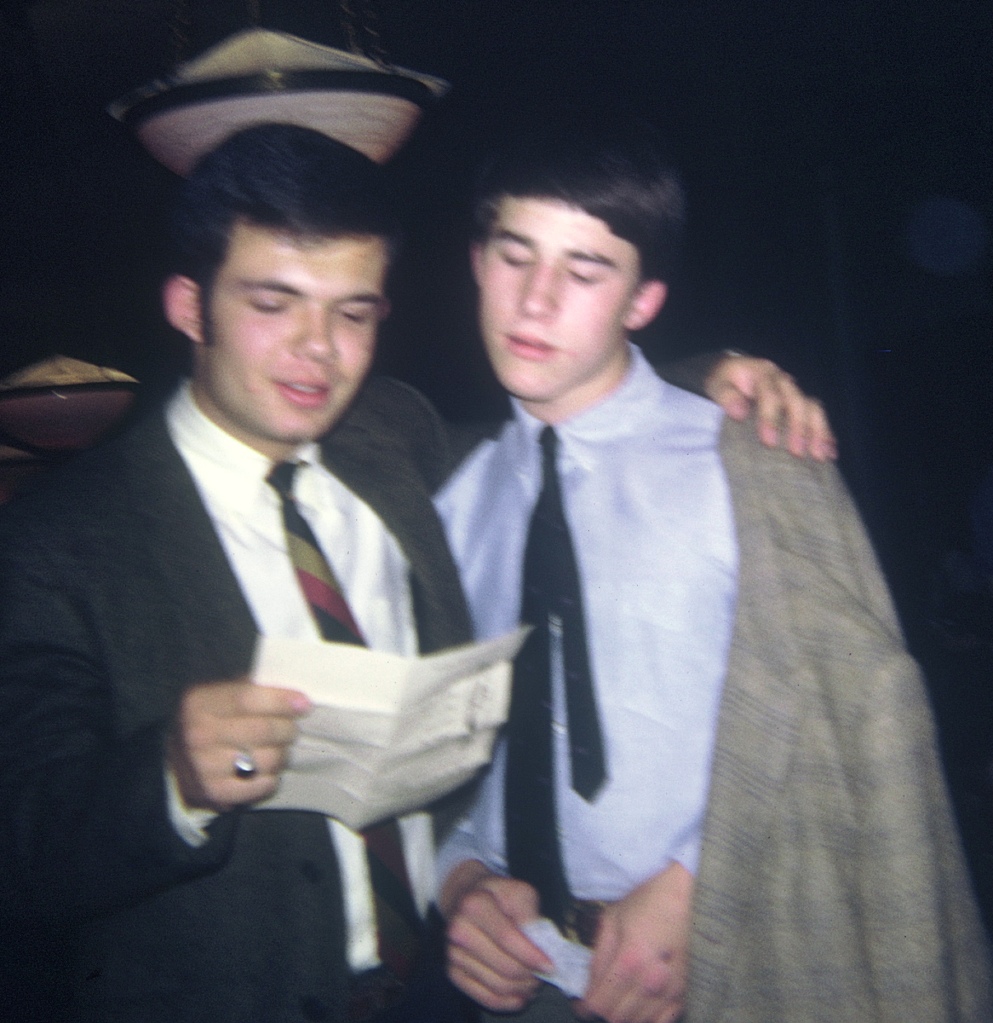

love these pictures- were we ever really that young??

This brought back lots of my memories. I’d forgotten about hall passes, hall monitors, etc., etc.

Sorry you’re bringing it to an end for the year.