Until college, I had no idea that freedom could be associated in any way with the word school.

In high school, the piercing tremolo of the electronic school “bell” controlled our lives. It rang almost two dozen times each day, the first blast signaling it was time to stop the sweet, before-school socializing with friends and ordering us inside to our stuffy, artificially lit homerooms where the ancient fluorescent lights buzzed and blinked above us.

The rooms were filled with the smells of musty, 50-year-old text books, yellowed and brittle pull-down maps of a pre-war world and 30 kids, most of whom had – that morning – lavishly applied the latest cologne or perfume being marketed as a sure-fire aphrodisiac.

Then, throughout the day, at 45-minute intervals, the bell paced our lives, signaling the end of one class and offering 3 minutes of freedom before ringing again and strapping us down to serve another 45 minute sentence.

In high school, I lived for the freedom and socializing of those three-minute passing periods.

So when I got to college and realized there was no bell controlling my life, there was no one taking attendance and my academic life was mine to control, I plunged into the deep end of the freedom pool.

Starting out, I did go to my classes regularly. It was ingrained. I could still hear the bell in my head. But soon, going to my Spanish class proved more and more difficult. After all, it was my first class of the day. At 10 a.m. I had to get up by 8 if I wanted breakfast, easily the most adequate meal the dorm cafeteria produced. Or I could sleep in until 9:15 if I just wanted to shower and shave before class.

I had been taking Spanish since the fifth grade when it was introduced with a slide projector, stick figures and rudimentary phrases repeated over and over and over again.

Narrator on the accompanying record: “Yo soy un hombre.”

Class of less than enthused 5th graders: “Yo soy un hombre.”

Narrator on the accompanying record again: “Yo soy un hombre.”

Class of even less-than-enthused 5th graders: “Yo soy un hombre.”

I hated it. Not the language, but the way it was taught. It was just like the nuns taught us religion at Saturday school at the local Catholic grade school. In those days Catholic kids had NO free days. School five days a week, church on Sundays and all Holy Days and our religious training on Saturday mornings. We had to study the Baltimore Catechism and memorize the exact answers to the questions at the end of each chapter.

The exercises started out pretty easy. So easy I still remember the first couple of answers 60 years later.

First question: Who made the world?

First answer: God made the world.

Second question: Who is God?

Second answer: God is the Creator of heaven and earth, and of all things.

And then each answer gets longer and longer. Question #12 was a doozie. You had to recite a 113-word prayer, The Apostle’s Creed. This was in 5th grade. I was just getting the hang of the Hail Mary.

I would wait until Friday night and try to memorize the answers but after the first few weeks, as the responses got longer and more complex, my cramming would inevitably fail me. Then, the next morning, Sister Mary Frances would threaten me with a graphic tale of eternal damnation if I didn’t memorize it by the NEXT week.

Getting yelled at by nuns who seemed to be guarding the religion from public school kids rather than lovingly inviting us into it, combined with the rote memorization, taught me to dislike that style of learning. If only I had known that they weren’t going to kick me out of the religion if I didn’t memorize the answers, perhaps I wouldn’t have been as terrorized. And I most certainly would have skipped Saturday school more often.

So with a background of seven years memorizing Spanish in grade school and junior and senior high school, I was a bit advanced for a college Spanish 101 class.

By the time the professor realized that I should have been enrolled in Spanish 102, it was too late for me to switch classes. She told me I didn’t have to come everyday because that would allow her to work more with the other students.

“Don’t disappear,” she advised, “but you won’t have to work too hard to get an A.”

She obviously didn’t realize she was talking to a freshman with a terrible academic track record. I did disappear from that class and didn’t work at all, except on my sleeping. Spanish was my only morning class and after I had what I took as permission to skip, I slept through every Spanish class the rest of the semester.

I did show up for the final – and can still remember the very disappointed look of the professor. I think she realized her mistake – and mine, obviously. My previous knowledge helped me through the final, but there was no A for me. The B I managed turned out to be the only decent grade I got that semester.

Though it took many years to sink in, I learned from that episode. I am careful with what I say to students, especially freshmen. There is so much of their new life spinning in their heads that while they often may understand the individual words that I say, but they may not understand their meaning in the context of the full statement.

I don’t remember much about move-in day except Doom and me hauling my belongings up to room 520 on the 5th floor of White Hall and Mom putting things in the dresser. She made me make the bed, something I had never done before. I really didn’t have that much to unpack: just my clothes and my stereo, which at that time consisted of an old Sony reel-to-reel with a built in amplifier and attached speakers that Doom had used in his presentations and about seven tapes.

When we were finished, we went off to get something to eat and then Mom and Doom hit the road for the hour and a half ride back to West Hartford. I went back up to my room. My two other roommates hadn’t arrived yet.

I’d been itching to be on my own – and had acted as if I were – the last two years of high school. I didn’t need parental supervision. I used my family for financial support, meals and a place to sleep, but emotionally after the death of Page, I thought my life was in the outside world. I didn’t need the family. That was for kids.

But I began missing them five minutes after they left. I was in this massive dorm, with the constant movement and chatter of people in the hallway and suddenly felt very alone. I had never stepped foot on the campus of Northeastern University before the day Mom and Doom dropped me off. I didn’t know what I was getting into.

I had thought I was worldly. I had been to Woodstock. I had worked on construction sites. I had driven a truck. I had dated pretty girls. I had lost a brother. I thought I had been a big shot in high school, knowing everybody and everybody knowing me. Now, in this new environment, I knew nobody. And no one knew me.

I sat on the edge of my bed thinking my life was starting over as I waited for my roommates to arrive. Those roommates proved to be a bit of a challenge. They put three of us into a space far more suitable for two. And when there are three in a group, someone is always the odd man out. In this case it was me.

But thankfully, I had read “Lord of the Flies” in high school and it prepared me for living in a freshmen dorm with about 400 other 18-year-old boys. By age, we may have been classified as draft-eligible men, but by behavior, we definitely were still boys.

The first roommate to arrive was Steve, a kid from a New York suburb. I figured we’d have no problem getting along as his suburb had a similar makeup as mine did. He seemed like a braniac, nerd type of guy. I had gotten along with those guys in high school. I didn’t hang out with them, but I’d gotten along with them.

And at first, I did get along with him. Most of the first day. Steve initially seemed like a good guy – a little over eager and a little talkative, but I chalked that up to first day nerves. Very quickly, though, within a couple of hours, he soon became very interested in anything I was doing. By the end of the second day, he became clingy, increasingly nosy and very concerned about my talking to anyone who wasn’t part of our roommate threesome.

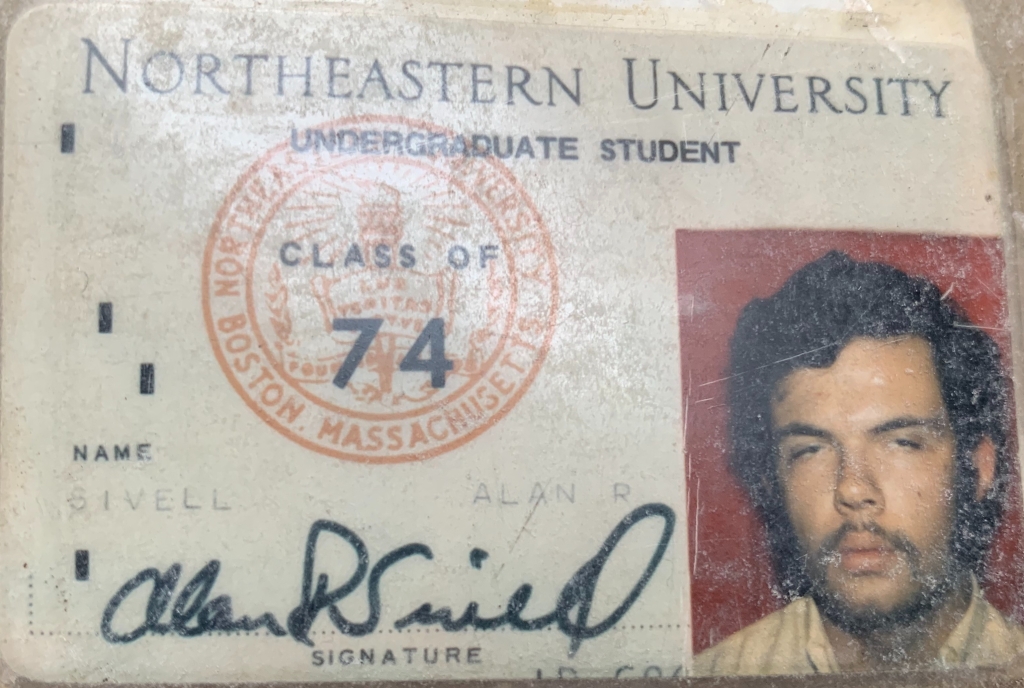

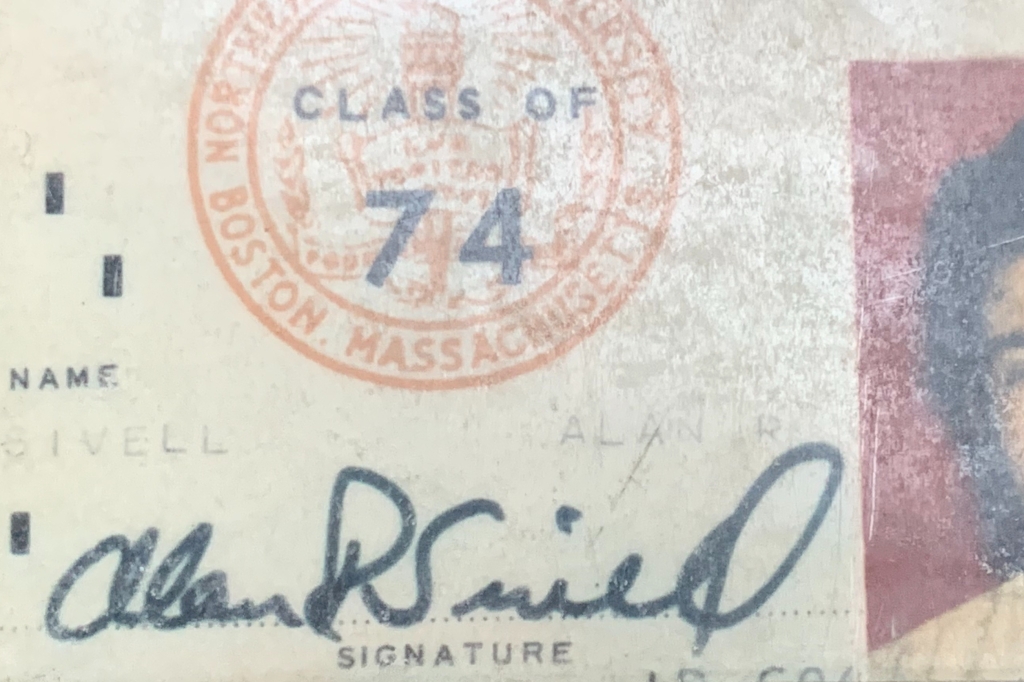

I decided to give him enough space to find someone else to cling to. I started leaving my room early in the morning and not coming back until late at night, exploring the city: walking the Freedom Trail and riding the subway to the end of the line and back. And it was apparent, judging by the picture taken for my student ID on the second day, I also spent time at a few bars that were happy to serve students, regardless of age.

Steve quickly sensed our incompatibility and made friends with some guys down the hall. He moved in with them when one of their roommates dropped out soon after classes started.

We got along much better after that. One down, one to go.

My other roommate, Milo, was a little harder to shake. Like a lot of guys at age 18, he was very sensitive about his masculinity. So one of the first things he did upon arriving was announce that his name was Mike.

He was the son of immigrants who spoke their native language better than English and came from a blue-collar town that didn’t send many of its sons and daughters to college. While I truthfully may not have been as worldly as I let on, at least I had been out of New England twice on weeklong trips, one to upstate New York where the highlight of the trip was touring the Utica Club Brewery and one week in Washington D. C. as part of a school exchange. Mike, on the other hand, had rarely been out of his factory-filled town of East Shoe, north of Boston.

I don’t know what challenges life inside the classroom posed for Mike, but life outside proved difficult for him. He immediately took a liking to the social atmosphere of the frat party. He was like the midlife salesman who goes to a convention and stays drunk for three days.

Since he never had consumed alcohol before, Mike didn’t know how to handle it and it didn’t take him long to get drunk. He wasn’t the brightest guy in the world to begin with and when he was drunk, he was less so.

If a party started at 8, Mike was slurring his words by 8:15 and trying to slobber on some poor girl’s neck by 8:30. By 9 or so, you could count on Mike to be sleeping it off wherever he might have landed: a couch, the floor, the front steps. If he was in the way, we would drag him into a closet, shut the door and let him find his way home. Once we did that on a Friday night and didn’t see him again until Monday morning, just before his Western Civilization lecture.

It wasn’t long before I stopped inviting Mike to come to parties with me. But by then, he was addicted to the social scene. He found parties on his own. And he found them every night. He learned how to buy his own booze or get someone to buy it for him. I was feeling really guilty. I had met his parents and even though they were just in their 40s, they reminded me of my grandmother and her immigrant roots.

You could tell by the lines on their faces and their hands that they worked hard – probably taking any overtime offered at their factory – and sacrificed to give their son a better life. They were going to die early for it and their son was drinking up his opportunity.

When he was in the room, he wasn’t studying. He was writing to some girl back home, the daughter of a woman who worked with his mother. Each letter would take about 7 or 8 other attempts. He’d write a few lines, read them to himself half aloud, then crumple the paper up and toss it in the wastebasket. When he got closer to what he regarded as a finished attempt, he’d read it aloud to me, since I was a journalism major and he regarded me as a writer.

The letters were painfully awkward, even for an 18 year old away at college. It seemed as if they were something Booth Tarkington would have written about to point out the awkwardness of the teen-age years. The poor guy. He was lonely and I was relentlessly trying to get him to move out, perhaps down the hall to join Steve if and when another bed opened up.

From time to time, I would feel guilty and vow to take him under my wing, this time in a positive way. But any sympathy I felt disappeared the night I came home and the room smelled as if someone had thrown up. Because Mike had. The room was dark, but I could hear him, in the upper bunk, spitting, trying to get the taste out of his mouth. He repeatedly assured me he was spitting on himself and into his own bed.

This admission didn’t reassure me much, but somehow, I managed to ignore the situation and fell asleep. It was my only escape. But about an hour later, there was a mad scramble as Mike leaped off the top bunk and found a waste paper basket and threw up again. As he started to climb back into bed, I yelled, “Wait a minute, jerkface!” Or words to that effect. “You’re not going to leave that puke in here. Clean it up. It stinks.”

I was pretty mad because the wastepaper basket was one I had made in Cub Scouts, about the only thing I ever did in Cub Scouts. It was painted New York Yankees blue and had stickers of baseball players that had come with the cards I bought in 5th grade. It had been with me about half a lifetime at that point and meant something to me. So I wanted it clean.

But my roommate wasn’t the brightest guy. Even when sober. After hearing my command, Mike, in a seamless series of motions, dropped down from his bunk, opened the window of our 5th floor room, grabbed the bucket of puke and pitched it out the window. By the time it landed in the dormitory courtyard, splashing on several couples that were saying their intimate goodnights in the last few minutes before curfew, Mike had closed the window, leaped back into bed and was snoring.

The next day, I contacted my RA about getting a new roommate. I used the bucket of puke in the courtyard – which by then was the talk of the dorm – as my leverage. The RA said he’d see what he could do.

Next time: Chapter 27: From Right to Left

Categories: My story

Keep writing!