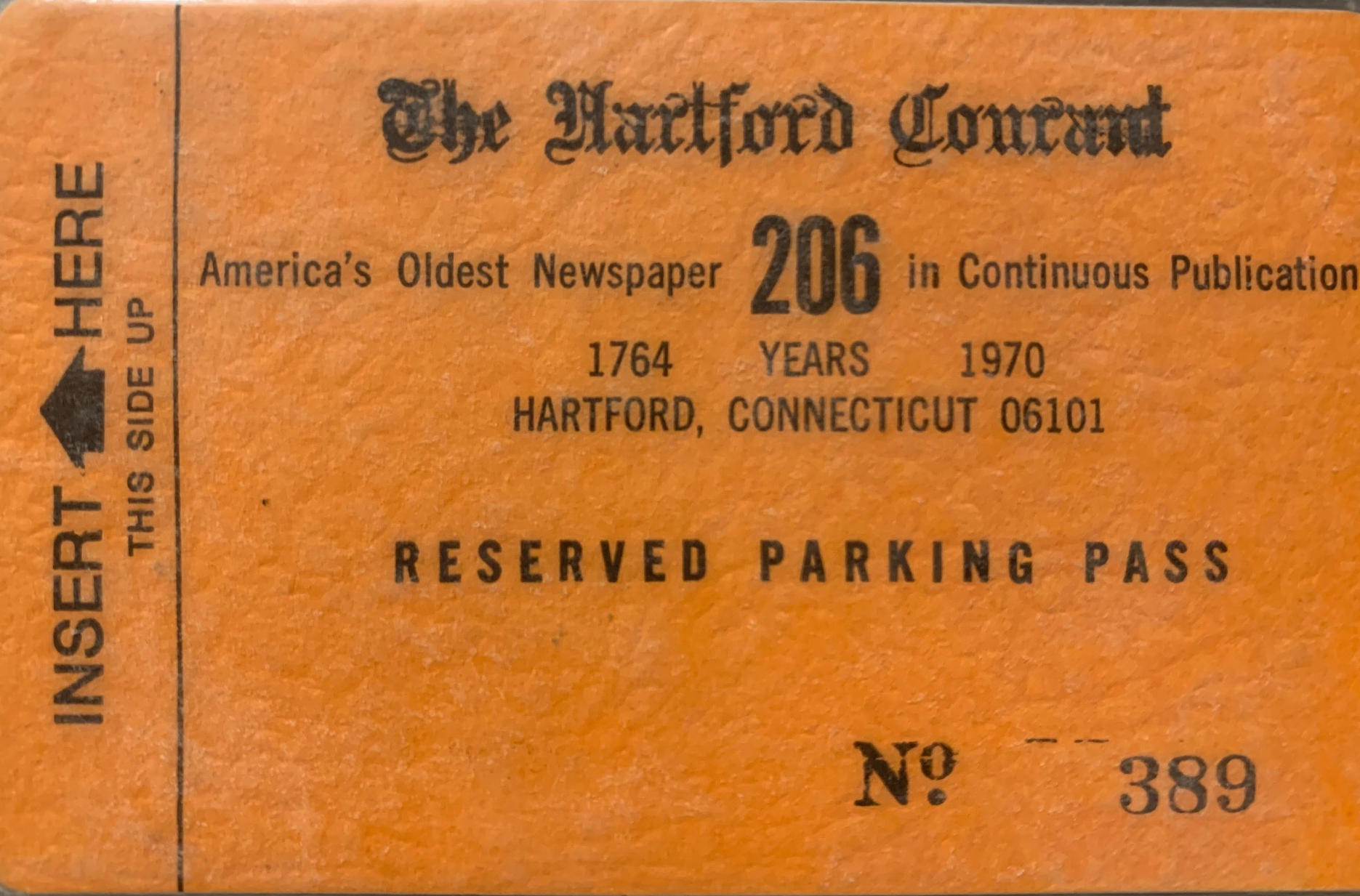

I drove down Farmington Avenue shaking with excitement and nervousness. I was heading to an interview for a paid, three-month co-op job at the Hartford Courant. The only thing that could have topped this interview would have been one with the Yankees.

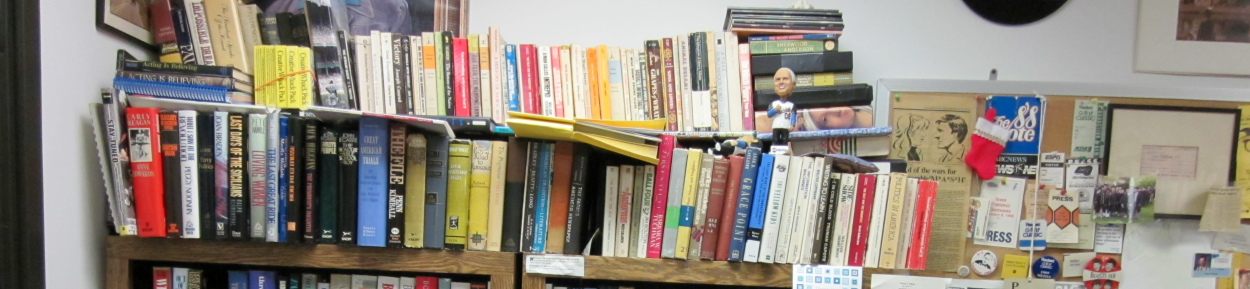

I’d been reading the Courant since I was a 9-year-old, searching for the day after recaps and box scores of baseball games. I’d graduated to also reading Dear Abby’s advice column and snipping the weekly top 40 record surveys the local radio station published. And I was beginning to read more and more of the news stories now that my interest in politics and the anti-war movement had been piqued.

It’s not unusual for readers to have an attachment to the newspaper they had grown up reading. I was no different: I loved my hometown paper. I viewed the reporters with awe. They were my celebrities.

The interview was part of the Northeastern plan. The first year at the school, students went full time. Then, for the next four years, we went to school for a quarter, then got a job in our field the next, then went back to school for a quarter and so on until graduation. The plan took a year longer, but the idea was to not only got experience for a career, but also to earn money to pay for school.

The school didn’t actually get you the job, though. It gave you leads and you had to interview and land the job yourself. Applying to the Courant and getting the job seemed, in my mind, to be my destiny.

Reading and writing were the two subjects I did well in without really trying. So when I examined all the majors at Northeastern (something I probably should have done before choosing the school), journalism seemed to make the most sense.

I knew I was good with words going back to 2nd grade when – just before Christmas – my favorite teacher, Mrs. Darrow, had a contest to see who could make the most words out of “Merry Christmas” and “Happy New Year.” I won a 5-pound box of candy that had two-layers of chocolates. And for the rest of my public-school career, when we had to write sentences as part of an English or grammar exercise, I would invent elaborate one-sentence stories in an effort to make the class laugh, cry or be grossed out.

And, truth be told, being a Superman fan also played a part in choosing my major. I might have been swept up by the Man of Steel’s powers, but I was just as intrigued by the folks at the Daily Planet who seemed to live at the center of the action in Metropolis.

I hadn’t worked on my high school paper or had much journalism course work. In fact, I had taken only two journalism courses up to that point and one was a journalism history course. I was midway through my sophomore year, after all.

I skipped breakfast on the day of the interview. I was too nervous. Putting on a suit, which was not my everyday attire, didn’t help calm me down. I felt as if I was wearing my father’s clothes. When I found a parking spot two blocks from the Courant, I had to spend several minutes psyching myself up to get out of the car and keep my appointment.

When the guy from human resources sat down with me, he pulled out my resume and high school and college transcripts and studied them for several minutes. A very uncomfortable several minutes. It became obvious he was underwhelmed and didn’t want to give me the test. Why bother?

But finally, he gave me the test. It was an hour of grammar, editing and writing problems. When I was done, I waited, watching time on the big clock slowly tick by, while it was scored. The wait was interminable. It reminded me of the times I’d been in the principal’s office … or at the police station with Page.

Finally, the guy – whose sole job at this wonderful newspaper seemed to be giving grammar and writing tests to applicants – came back with the scored test with a surprised look on his face. He took another look at my transcripts and then at the test again. I had done so well, he felt as though he had no choice; he had to give me the position. But he also gave me a lecture – one that I had heard several times before – about my grades and the importance of applying oneself.

So I got the job for $2.10 an hour, more than the $1.60 I had been making scooping ice cream at Lincoln Dairy two summers before but less than the $2.50 I had made at Genovese and DiDonno hauling ceiling tile. I was ecstatic. I would be working 40 hours a week, getting paid and getting college credit. I was living at home so I was able to save money.

And I was working at the Hartford Courant.

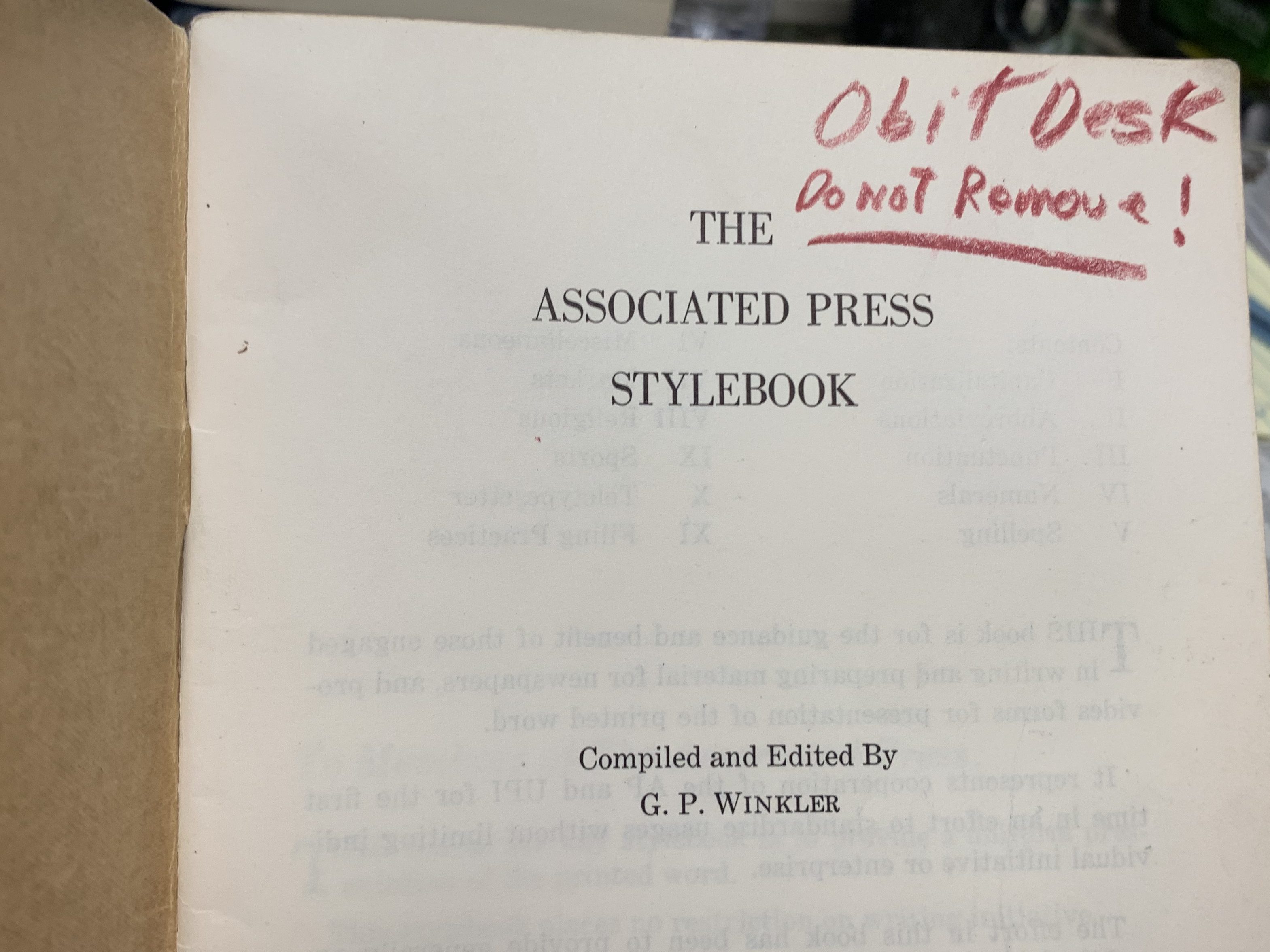

The actual, everyday drudgery of the job, though, quickly brought me back to earth. I was assigned, along with another Northeastern co-op student, Joe Nunes, to the obituary desk. Joe always had a smile and could see humor and irony in almost any of the situations we lowlifes found ourselves in. We liked each other instantly. For the 3 days that our shifts overlapped, the obit job was bearable.

“Best training job for rookie journalists,” we were told by our trainer. “You’re going to learn to type much faster and know your keys because obituaries have lots of names, numbers and punctuation. And, the obit page is the most read page in the paper, so if you make a mistake, you’ll hear about.”

Joe and I wore an old fashioned and uncomfortable headphone-speaker combo that you see telephone operators wearing in the old black and white movies and took dictation from funeral directors all day. We didn’t have a phone on our desk. It was a box built into the desk that you switched on whenever a funeral director called. For 40 hours a week, every story we typed ended in death.

These days, newspapers charge for families to put obituaries in the paper. Since these are basically paid notices, the funeral directors just fax or e-mail any info about the deceased they want … since the paying customer is always right. When Joe and I were manning the obit desk, obits were not paid death notices. They were considered “news” and everybody made it into the paper. But to maintain control of the space and decorum on it pages, The Courant had a very specific style for obits. No deviations.

All the funeral homes had the Courant’s style sheet and had been told to insert the name and basic life facts of the deceased into these forms. But Weinstein Mortuary, along with some others, was always trying to impress their clients by getting just a little more than allowed into the paper and they would add these flourishes to the obit – adjectives and adverbs – that just weren’t allowed.

Joe and I would have to stop them every other sentence or so and say no, you can’t say it that way. And they would argue with us and eventually after wearing us down a bit with their parsing, we would compromise and continue. But there was no compromising in the Courant’s system. We’d drop off our copy at the city editor’s desk and almost instantly get called back up to fix the rule that had been imperceptibly bent.

So we got harder and harder with the funeral directors as we learned the system. In fact, we enjoyed getting harder because it was the only power we had. We were the lowest of the low in that newsroom and the building, in fact.

The dream job, in fact, rather quickly turned into a nightmare. Few in the newsroom talked to the interns. And when they did, it was to tell us to run an errand or to point out something I had done wrong.

Each story was returned multiple times smothered with bold, red revisions written with a grease pencil thicker than a toddler’s crayon. Even the woman who ran the snack room had complaints about me. I was on a cheese and orange diet (for the past 40 years, I’ve thought I needed to be 10 pounds lighter than whatever my weight happened to be). Even though I usually bought a drink to go with my cheese and orange, the old bat would exert the only power she had and bitch at me for not buying her food.

Joe fared a lot better. He got sent out on several stories. Many more than I did. A few of the editors liked him and asked him to come back again and again. He was still there almost 40 years later, having risen through the ranks to be an editor himself. He has to have been there longer than anyone in that building.

I did manage to get two bylines during my time at the paper. One was on the weekend when one of the neighboring towns, West Hartford, was opening a police firing range. Not that’s not that big of a story, but the beat writer for that town must have promised someone that it would be covered. Probably to make the reporter look good to the cops on his beat.

The call came in to remind the weekend city editor, Owen McInally (one of the few people in the newsroom who was nice to the interns). He and I were the only two people in the big football field of a newsroom. I could see him at the other end of the newsroom as he stood up and stared out at all the empty desks and consider his options. Who could he send on the story? He must have spent a full 5 minutes considering his options. His eyes seemed to stop at every desk and wish that there was someone sitting there that he could send on this story.

I know now he was probably thinking if he sent the kid on the obit desk, his life would be so much more difficult that day because he would have to hold the kid’s hand all the way through the story and even after hours and hours of work on an inane, simple story, he still might engender a lawsuit. On the other hand, if he didn’t send someone to cover it, he’d have to deal with the complaining of that beat reporter for week or months. Grudges last a long time in the newsroom.

Finally he called me up to his desk and gave me the assignment. And he did have to hold my hand, every step of the way – on how to get there, what to ask, how to write it. I read it now and it’s in a voice that is nothing like mine. It is much better than anything I could have written at that time.

I began to dread my days at the Courant. I wasn’t ready. I had taken a 3-month reporting class and we didn’t do any actual reporting. We rewrote stories out of a journalism textbook. We did take a tour of the Christian Science Monitor. I remember sitting in the lobby waiting to see someone important. But those 3 months at the Courant, I lived in fear someone would talk to me. Because the talk wasn’t going to be friendly. No one there had use for interns. Now, after having been in a newsroom and knowing news people, I realize it was nothing personal. Many news folks are busy and don’t tend to be that welcoming to newcomers, especially interns because they aren’t going to be there very long. I guess it’s a way of weeding them out.

I eventually did get weeded out. The beetle-browed editor, Irving Kravsow called me in to a meeting near the end of my co-op. Up until then, he hadn’t said a word to me. Kravsow was dark and swarthy and wore a permanent scowl. I now know and understand that look. It gives away nothing and puts the receiver of the scowl on the defensive. It’s a look cops and hard-edged reporters use to their advantage in interviews.

As I approached his office, I was as nervous as I had been when I first drove down Farmington Avenue for my interview three months before. I knew I wasn’t doing that great but I had been trying as best I could. But I really didn’t know HOW to try.

I was 19, a year out of high school in my first stab at a real job. I was hoping that Kravsow was going to tell me what I needed to work on at school before coming back for the next co-op session in the summer. No such luck.

Like the chat I had with Mr. DeSalvo when he told me that Page had died, this meeting had a profound effect on my life. Kravsow told me I wasn’t being invited back, telling me bluntly that I showed little talent for the newspaper business.

And then, I guess to soften the blow, he tried to play career counselor.

“Isn’t there something else you would rather do with your life other than journalism?” he asked.

“No,” I muttered softly, mostly to myself.

I was devastated.

Next time: Chapter 31: Should I Stay or Should I Go?

Categories: My story