Extracurricular activities had been my thing in high school. Hub of the action, the yearbook proclaimed. I had expected that would be the case in college, too. But, at Northeastern, it didn’t work out that way. There were no sports, clubs or organizations for me.

Early on freshman year, I was too busy with my new found friends and passion for playing cards and drinking beer in my spare time to get my butt out of the dorm and into active university life. Besides, I thought, this school is so big, they probably have enough students to fill every role already. They don’t need me.

But I felt differently about the baseball team. My passion for the sport – then and now – is something I can’t explain. I decided to try out for the team. I actually went to the open tryout – at a Division 1 school.

I didn’t know the players that were going to make the team had been recruited and were already on scholarships. And even most walk-ons were there because they were invited to walk on. I thought everyone just tried out like high school. There was a line of a dozen or more kids – like me but likely more talented – at each position. I took one look at that and left. I knew my chances. I had barely made my high school team. And it was a small high school.

If you wanted to participate at Northeastern, you had to make the effort at several organizations to find you niche. At Hampden-Sydney, on the other hand, little effort was needed. Lots of organizations wanted your participation. You could pick and choose your extracurriculars and be assured a spot.

I played substantial minutes and scored a try in my first rugby game. At the campus radio station, I was accepted as an equal member of the group at the first meeting I attended. I was asked what my interests were and what job I’d like in addition to my on-air shift every Sunday night.

Since I had had so much success in being a joiner at this small school, I decided to make one more stab at my passion: I went out for the baseball team.

What I didn’t realize was that at Hampden-Sydney, there were no scholarship players. There were no long lines of guys vying for every position. In fact, there were no cuts. Everyone who came out for the team, made the team.

I didn’t know about no cut policy when I convinced Harvey to try out with me. But I figured it was a small school. Surely they could use the bodies. We met in a classroom at the gym and the coach was the very successful, grouchy football coach. He was a hard-nosed guy with old-fashioned values who pushed the guys hard. But baseball was a more nuanced game and it wasn’t his primary game.

Two things Coach Fulton said stand out from that first meeting. The first was that we shouldn’t hang our arms out the car window while driving because the cold air will hurt them. As proof, he said he was 50 years old, never had a sore arm and still threw batting practice. And he could throw it all day, every day. Because he never drove hanging his arm out the window.

That seemed plausible to me, since, as a left-hander, my left arm was always hanging out the window on nice days. But I wondered how that made any sense for right-handers.

Then second thing was when he was talking about our uniforms and appearance. He suddenly stopped and fixed his gaze on me in the back of the room and my pile of hair. It was freshly washed and since I didn’t have a hair dryer, I dried it by putting the top down in my convertible and driving the back roads near campus while standing up.

Coach Fulton paused a beat or two while everyone turned to see what he was looking at.

“Son, I don’t have a hat that’s gonna fit you!” he said as his eyes bulged.

His delivery was part shock at how big my hair was, part admonishment, part instruction for the team. Everyone laughed at his unintentional brilliant delivery and timing. That was the moment that I realized that everyone made the team, no matter how bad they were. Or how big their hair was.

I was hoping there were lousier players than Harv and me. But no. Once we got on the field, it was apparent, Harv and I were at the bottom. He and I used to jokingly argue who was the 18th guy on the 18 man team.

I did get a nickname. Even though it was a bit long, everyday, invariably, one of the guys would greet me with “Son, I don’t have a hat that’s gonna fit you!” Eventually, it was shortened to just, “Son …” with the rest left unsaid.

Coach was a successful football coach, taking his team to the Knute Rockne Bowl two years in a row, but wasn’t as tuned in when it came to baseball. This is not the comment of a disgruntled player who didn’t get much playing time. Any time I got was more than I deserved. I’m guessing he was the baseball coach because he needed something to do in the spring. He often didn’t know who the baseball players were unless they also played football.

Fred Larmore, who was a junior and a baseball captain, did not play football. He was a very nice guy and on one of the first days of practice, Larmore and I were the first guys out of the locker room and were outside the gym warming up. The coach, since this was the first really nice day of the year, also decided to get out on the field early and chat with his favorite players while they warmed up. But as he came through the doors, he saw there was only Fred and me.

He was trapped. If he went back inside, it would look like he didn’t want to talk to us. I knew he wouldn’t make small talk with me. Heck, I didn’t have a hat that fit. But he knew Larmore’s name, at least. So he watched us for a few minutes and was formulating something to say. There had been several uncomfortable moments of silence since Fred and I weren’t talking now either.

“So what are you going to be doing next year, Larmore?” the coach asks, finally.

Fred was taken aback. He was a junior. And he was a captain of the team. However, he was the type of guy who respected his elders and his coaches. Didn’t question their sanity or the quirks of their personality.

“I hope to be here, sir,” he replied.

“Oh,” coach said and he turned and started walking toward the field. “Great.” Coach had no guile. He didn’t pretend that he knew that all along. He just took that answer in as if Fred had said he was going to law school or med school.

I just tried to stay out of the guy’s way while I watched with amusement. Which wasn’t hard as he acted as if I were invisible. That was OK. All I wanted was a chance to put on the uniform, play catch everyday, get some batting practice and have a seat on the bench at the games.

We were juniors but Harv and I mostly played on the junior varsity. Which was fine with us. We’d rather sit on the bench with guys who were a little better than us than with guys who were a lot better. And we got into the games occasionally when we were way ahead or behind or when the assistant coach just felt like it.

JV Coach Zeno was a jock through and through, but he liked my sense of humor. And the fact that I was willing to drive the 2nd van. Since I had experience driving bigger trucks, an extended van didn’t bother me the way it did a lot of the guys at the school who only had experience driving their Corvettes or Citroens.

I got 10 at bats my senior year. One was against a guy at Lynchburg College who later signed with the Detroit Tigers. He was throwing the ball so fast you couldn’t see it. You couldn’t. It was just a sound that went by you. If it hit you, it would have gone through you. It seemed as if it was going 120 mph, but was probably only 90 or so.

I was so scared when I was up there. I didn’t know whether to swing every time with the hopes of hitting the ball, perhaps getting the timing down by the third swing. Maybe if I started to swing by the time he brought his arm back. Or if I should just stand up there and hope he walks me. He was wild and that was part of the reason he didn’t make the major leagues. And why people didn’t dig in against him.

I swung at a couple and watched a couple and in 5 pitches I was back on the bench. Happily. The guy was frightening. I was beginning to realize that my dreams of playing baseball beyond this level were fading. OK, they already had gone to black but I still harbored a fantasy. In truth, I held onto it until Dave Winfield, who was born the same year I was, retired. He was a superb athlete who had been drafted in three professional sports and if he could no longer play, then I reasoned, I probably could no longer play.

Then we played a double header at William and Mary, a division I school. In the first game, I hit the ball hard twice, but had grounded out and lined out to the second basemen. The third time up, Harv was on second, having singled and been moved over on a walk. Approaching the plate, I felt I deserved a hit after making good contact first two times with nothing to show for it.

After throwing me a fastball and a curve that came nowhere near the plate, the pitcher threw a pitch that I could see coming the whole way. I saw it so well, a change-up coming in just a teeny bit high and and a teeny bit outside, that I had time to have a conversation with myself. Should I swing or wait for possibly a better one? But maybe I won’t get a better one. Maybe, this is it.

If I swing, chances are I won’t pull it and getting my arms up there to swing will take a lot of strength so if I do hit it, it might not go that far. But if I wait, I might not get another one this fat. All this took place in the less than two seconds it took for the ball to get from the pitcher’s hand to the proximity of the plate. Finally, late even for a slow pitch, I decided to swing.

I swung as hard as I could and got the fat part of the bat on the ball. It was one of those times when you hit the ball so squarely and so hard, you don’t even feel the contact. There is no backward jerk of the bat, just forward motion. The ball took off arcing toward left field. Unfortunately, the last I saw as I took off for first base was that it seemed to be heading directly toward the left fielder. Crap.

But I ran hard as we had been taught since we were kids. You never know. What I didn’t know as I concentrated on getting to first base was that the ball had tremendous spin on it because I had swung so deep in the strike zone. The ball was slicing away from the left fielder who didn’t realize it until it was too late.

As I neared first base, I saw the ball bounce just inside fair territory and continue to spin off the diamond into foul territory with the LF in hot pursuit. Harv and another runner scored and I made it to second base standing up. Anyone else probably would have had a triple, but I was very pleased with where I was. The bench cheered wildly as teams do when a not very good member of the team does the ordinary: scores a basket, goal or gets a hit. I was enjoying the moment, standing atop second base and thinking I never realized how tall the bases were. But I didn’t want the other team to know that I had just done the unexpected. We won that game 4-0.

In the second game, I started a rally by getting on base with a drag bunt. Reading the account of the play, preserved in the school paper, one might come away with the impression that this was a strategic play by a speedy player, “Big Al” Sivell. But I was never speedy and never strategic in a baseball sense. But I always was strategic in a self preservation sense.

Their pitcher wasn’t tricky. He simply featured fastballs that I knew I couldn’t catch up to. So I just stuck out my bat and hoped he’d hit it. He did and, miraculously, the ball dribbled perfectly between him and the first baseman who both chased after it. By the time the second baseman got to the ball, there was no one covering first. I was safe. Sometimes, the tortise does indeed win the race.

An inning or two later, as I was standing in the outfield, the football team began to walk on the field. I tried to tell them to walk around but there were too many of them. And they were too big. Finally the William and Mary baseball coach went over to the players and told them to move. Then the football coach came over and gave a piece of his mind to the baseball coach. And in big time athletics, it is always football over baseball. So we had to call the game because football wanted part of the field.

My last career at bat came in a varsity game. It was at home and the head coach was gone and assistant coach Zeno was running the game. We were behind and the game was about over but we had a couple of guys on. He wanted to get me in the game because I was a senior, he liked my attitude and all my friends were at the game. In fact, they were the only people at the game.

Coach put me in to pinch hit. I decided to try the old bunt routine again. I knew if I tried swinging away and had the usual mental dialogue with myself that I had on each pitch, the catcher would be throwing the ball back to the pitcher by the time I had my mind made up whether to swing or not. With my pals coming alive on the sideline, I did manage to bunt the ball fair, dragging it down the first base line just as I had seen my idol, Mickey Mantle, do it dozens of times. But this time it wasn’t perfectly placed between the pitcher and first baseman and I didn’t have of Mickey Mantle’s speed. I was thrown out by a mile.

I didn’t care that I didn’t play much. I was on the team. I got practice everyday. Play catch. Take batting practice. Have a great seat in the dugout during games. My only disappointment during my Hampden-Sydney baseball career was that I was not in the team picture senior year.

There was a reason for that.

I had trimmed my hair a bit, but the coach was right. He didn’t really have a hat that fit me. Carefully positioned, and if I didn’t get too active while sitting on the bench, I could get it to sit right up on top. The coach never liked that. I’m pretty sure he made up his mind about me – a Yankee transfer – in that first meeting.

On picture day, Coach had told everyone on the team pictures would be taken for the yearbook a half hour before regular practice. So he told everyone to get dressed a half hour early. Everyone got the message – except for me.

I arrived on picture day at the usual time and was getting dressed for practice and the picture. It eventually dawned on me that I am the only one in the locker room. I wasn’t usually early but I was never late for baseball. I sensed something was out of whack so I dressed as fast as I could. When I burst out of the building to begin the long run past the football field to our diamond, off in the distance I could see the players gathering together near the bench.

Oh, crap. I was really late, I thought. Coach has gathered them for a meeting. Maybe going over signals for tomorrow’s game.

Then I saw the photographer. I suddenly realized what was happening and why everyone was early. In a desperate attempt, I tried to run faster. But it didn’t seem as if I was making any progress toward the diamond. Schools always seem to put the football field close and the ball diamond at the farthest reaches of the property. If I had been gifted with speed, maybe I could have made the last exposure. But just before I got to the field, the group began to break up and I knew I wasn’t going to make the 1973 team picture.

I wasn’t going to be in the yearbook. 50 years from now when I want to look back, it would be as if I was never on the team. Maybe that’s what the coach wanted. He had an idea of what ball players should look like and I certainly didn’t fit the picture.

Luckily, though, my disappointment didn’t last 50 years. I had friends in the press.

When I got back to the dorm that night I told the story. Some of the players on the team, who had seen me running across the field, felt for me and so did my pals in the dorms. Several of them were friends with the guys working on the yearbook. “Don’t worry,” they said, as if they were making a promise.

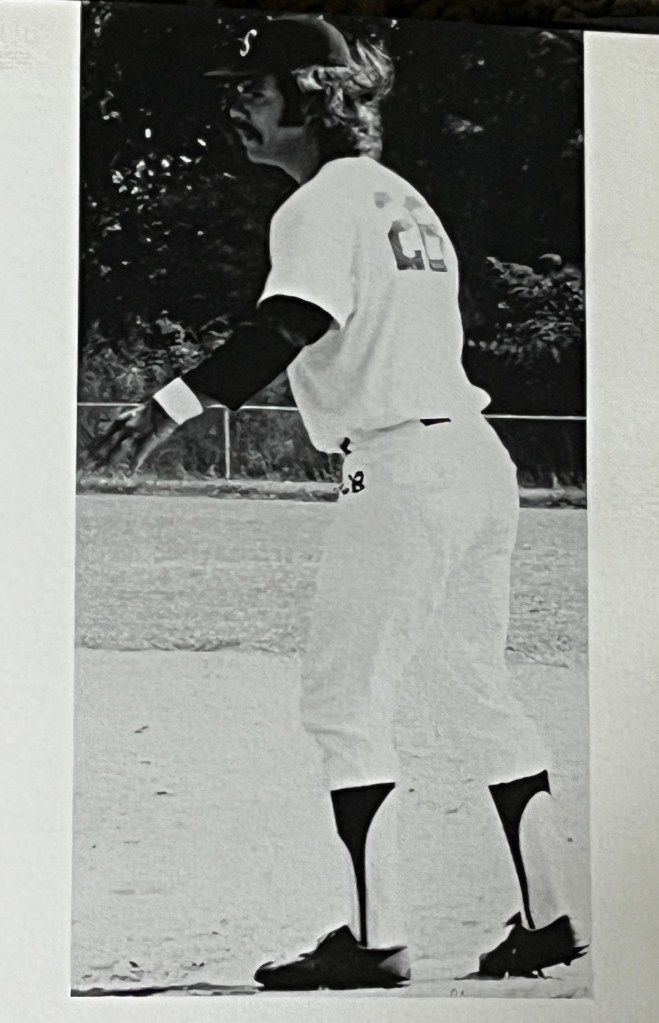

A few months later, after graduation, the yearbook arrived at my house. I quickly turned to the section on our season. There was the team picture without me. But … there was a very big individual picture of me in all my shaggy splendor, the glorious locks sticking out of a precariously placed cap. It looks as if I was, perhaps, leading off first base. Perhaps after a successful drag bunt.

I happen to know, though, I was coaching first base as I usually did to keep myself into the game. But it doesn’t matter. 50 years later and no one will know if I say I just hit a double at William and Mary. Or that it was taken just after I singled off a pitcher who threw a 100 miles per hour and had been drafted by the Tigers.

And I am sure, after all these years, even the editors of the yearbook and the guys who arranged the picture don’t remember why they featured that picture of the 18th player on an 18 man team.

Next time: Chapter 36: The Ezra Show

Categories: My story

Fun reads. I love baseball but never tried out on any level. I was never athletic.