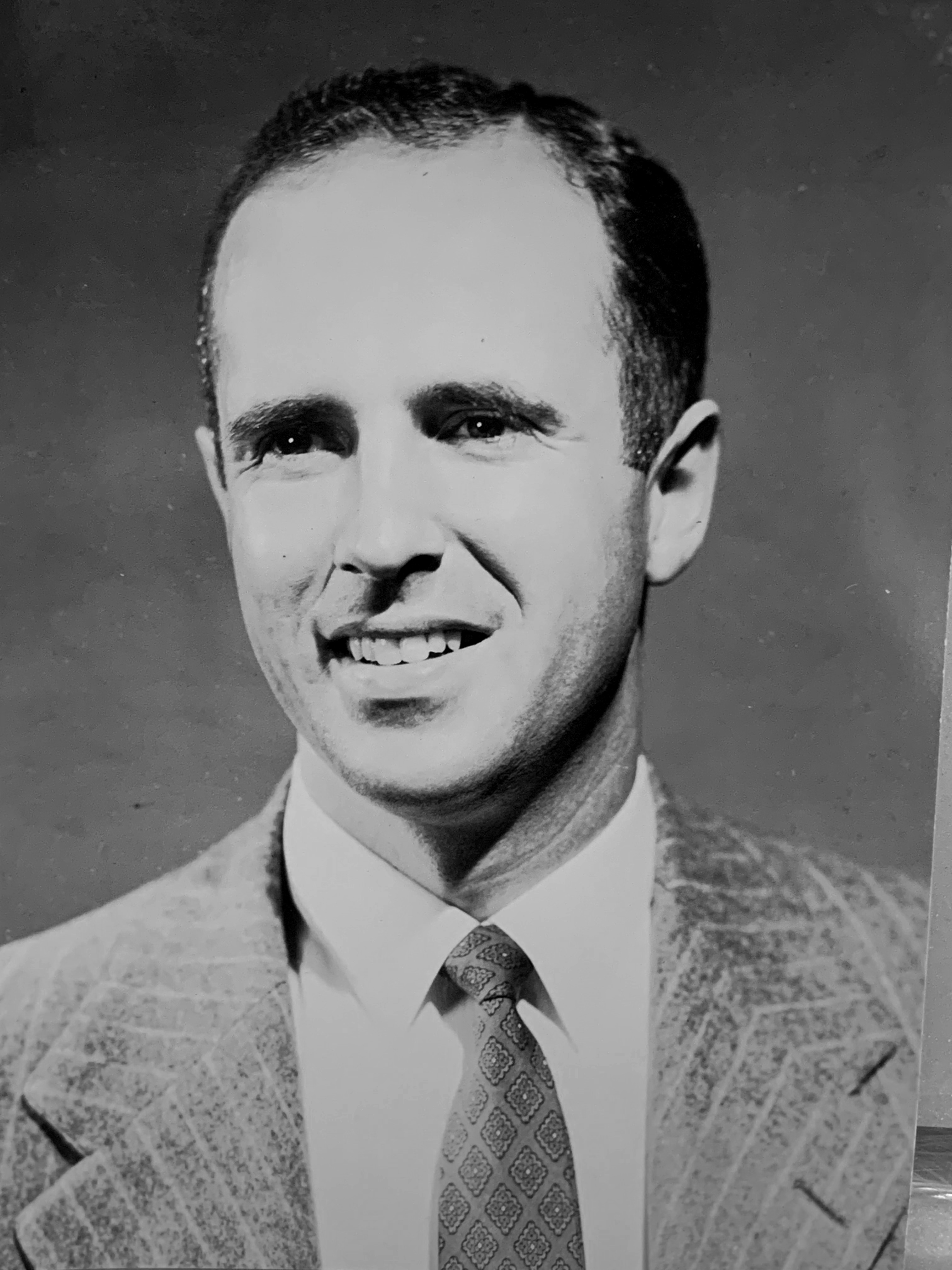

My father, Doom, had a couple of lines on the back of his neck that made what looked like the letter “X.” There was an indentation where the lines crossed. When we asked about it, he always said, “That’s where I got shot during the war.”

Until each one of us reached a certain age, we believed him. He was joking, of course. We tried to ask follow up questions, but Doom was the type of guy who let you know when he was or wasn’t taking follow-up questions. And he wasn’t on this subject.

Saying Doom didn’t talk much about his experiences during the war is an understatement. The only experience he talked about was when his supply ship pulled into a port on one of a thousand tiny islands in the Pacific and he ran into some of his college buddies. Other than that, nothing.

Years later, when I was visiting the WWII memorial in Washington, D.C. I called him on my cellphone to describe what I was seeing. I knew he’d been in the Pacific and I told him there was a listing of the major battles there. He asked me to read them to him. When I got to “Leyte Gulf,” he said, “That’s where I was.”

Like a lot of World War II vets whose coming of age coincided with the war years, he did his duty and was thankful to come home. He didn’t bring the war home with him.

Doom had been a chemistry major in college so it made sense that he start his career with a major chemical company, the Dupont Company in Wilmington, Delaware. He had gone to high school in Wilmington and that’s where his widowed mother was living after the war.

But Doom quickly learned, despite the fact that he could have a long, lucrative, stable career working for one of the top companies in the U.S., working in a lab wasn’t for him. He liked being outdoors and he liked people.

So he left DuPont to be a salesman for the Wood Conversion Company (a Weyerhauser company that later became Conwed when the consolidation craze began in the 70s). For the bulk of his career, he sold insulation and ceiling tile to contractors throughout Connecticut and upstate New York. The products were used in shopping centers, apartment complexes, schools and office buildings.

The job and the company proved a good fit and he did well. After winning many company sales awards, he was promoted to regional sales manager. In that position, his office continued to win awards. However, by the time the company misspelled his name on his commemorative 25-year plaque, he was disillusioned by how impersonal the company had become as it had grown. He advised me, “Don’t work for a big company.”

He stuck with his job for so long because he found he could make his sales quotas by noon or 1 and still have time for a round of golf or at least a bucket of balls at the driving range and make it home for dinner.

Besides his family and Mom, golf was his greatest passion in life. He usually had a couple of clubs in the car and at one point his handicap was seven.

He liked playing nice golf courses, but he was a public golf course kind of guy. The only golf club he belonged to was the Rockledge Golf Club, which was the pubic course owned by the town of West Hartford, where he lived. He served the course’s Men’s Club in various positions over his more than 40 years as a member. The Tuesday Tournament that he started is named in his honor.

Over the years, Doom accumulated many sets of clubs in his quest for the perfect set so he could play that perfect round. While he may not have told stories about the war, Doom had stories about each set of golf clubs. His favorite story – not his favorite set – was about the time a grateful customer, whom Doom had saved a bunch of money on a multi-million dollar deal, sent him to Indiana to be fitted for a custom set of clubs. There, his swing was videotaped and his arms, legs, torso, and hands were precisely measured. His grip and his stance were studied. These clubs were to be an extension of his body.

When Doom got home, and as he waited for his custom set to arrive, he liked to tell how professional and scientific these club makers had been. Many times. The clubs arrived and Doom played with them for awhile. But his game didn’t get better. It didn’t get worse, either. Save for a few clubs that did seem to improve his game, most of the fancy set eventually was relegated to the basement, alongside the other failed, golf club experiments.

Doom was a very strict, traditional dad of the 1950s. Dinner was served at 6:00. The phone was taken off the hook and not put back on until 7:00. The teaching of table manners continued until we grew up and left the house. There were instructions on how to hold our utensils, the size of a bite, how to pass food, and many, many more. Nothing was left to chance.

When we used the phone, we were to greet the person who answered, identify ourselves and then state our purpose. If our friends called and didn’t follow that protocol, we were to tell them that’s the protocol they had to follow when calling our house.

Both Mom and Doom had college degrees at a time when less than 5 percent of women and just over 6 per cent of men had degrees. So there were high academic expectations in the family and these were bolstered by our aptitude tests. But since Page and I were always more interested in our present day social lives than our academic futures, Doom established a study table in the kitchen.

Every grade below a B meant one afternoon per week at the table. You had to be home 15 minutes after school got out and be at the table in the breakfast room with your books open. You had to stay there until it was time to set the table for dinner, about two and a half hours. Some semesters I was at that table four afternoons a week. And that’s only because there wasn’t a study table on Fridays.

The kids all had chores: setting and clearing the table, washing and drying and putting away the dishes. Mowing the lawn. Probably the hardest task of all was holding the light for Doom while he worked on the furnace or the electrical panel, keeping the family’s turn-of-the-century house in good repair. You didn’t dare daydream and let the beam of light wander because you would hear about it. Picture Ralphie and his dad changing the tire in A Christmas Story. Only without the swearing. Doom didn’t swear.

He was very good with tools and didn’t mind climbing the ladder to the third floor to work on the roof or the security lights, even when he was well into his 70s. And when his 40-something neighbor was too nervous to climb that high, Doom did it for him, too.

Mom and Doom were always fixing things themselves partly because it was in their character to take control and partly because they had more kids than money. Not that we were poor, but now that we’ve cleaned out the old house and have seen how much money they earned, it’s obvious they had to struggle with money. They couldn’t have provided for us the way they did and not come close to the financial edge more than a few times.

I remember when Doom came home with a $300 Jacobsen lawn mower. In 1959. My mom had a fit. Usually, we never heard their arguments. So this had to be big if it broke into the public realm. I don’t know if I remember it because it was so big or if it was because my parents rarely argued in front of us. It was a lot of money in those days for a lawn mower, but in my dad’s defense, I mowed a lot of lawns with that mower. And it lasted more than 30 years.

My mom paid him back a few years later when she got a $500 Electrolux vacuum. There was nothing he could say. And in her defense, that vacuum also lasted more than 30 years.

His purchase of the ping-pong table was another bone of contention. He bought the most expensive one available. His thinking was, he could buy a cheap pool table or a really good ping-pong table. Considering how much we used it, he was right. It was worth the money.

We used it because Doom liked to play. Two or three nights a week, all winter long, after the dinner dishes were done, we’d all head down to the basement to play.

Doom was always up for fun. He liked to say that he and Liz set the all-time distance sledding record at Elizabeth Park after a mid-winter melt followed by a cold snap produced an icy hill. Using a runner sled, he, with Liz clinging to his back, rode the entire length of the Hartford side of the park and had to BRAKE so they didn’t go out into the street.

When we lived in upstate New York, he made an ice skating rink in the back yard every year. First, he would ring the back yard with 2X8s and then run the hose out of the basement and night after night lay a layer of water down until he had produced a skating rink 6 inches thick and as smooth as glass.

In the summer, when he wasn’t at the golf course, he was swimming. He was always in search of a new swimming hole, less crowded than the last. He discovered the Barkhamstead Reservoir before the crowds came. Then it was Stratton Brook. In later years, when there were no kids to go with, he enjoyed swimming his laps at Cornerstone and the Jewish Community Center.

With the house finally empty, Doom and Mom began ballroom dancing, often dancing several times a week and traveling up to Mass. or down to New York for a chance to get out on the floor. Even when visiting in Iowa, they made sure one night of their trip was reserved for their dancing addiction, either at the Col Ballroom or the Moline Elks Club.

And when I say addiction, it was not unusual to come into the kitchen and see these two 70 year olds sashaying (my mother’s word) on the linoleum floor, trying to master a new step.

Doom was a gentleman with old-fashioned manners that may seem quaint today. But shouldn’t. He always stood when a lady, or anyone, for that matter, entered a room. As I said, Doom didn’t swear. The closest he came, that I recall, was when a golfer on another fairway had been driving everyone around him crazy for several holes with his loud, obnoxious, drunken behavior.

“That man is an ass!” Doom sputtered. I was caddying for him that day and it was the strongest language I ever heard him use. And he used it only once.

He stopped smoking the day the first surgeon general’s report on the dangers of smoking came out in the mid 50s. He didn’t drink except when it was almost compulsory during the 50s and 60s and then it was whiskey sours.

For the last 30 years of his life, he preferred ice tea. And the 99-cent salad at Wendy’s.

He wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty when the job called for it, but he cared about his appearance. He always watched his weight. He didn’t set fashion trends, but he did follow them. The worst advice he ever gave me was when he advised me to buy a leisure suit.

Doom was still vigorous and outselling the other company salesmen in even bigger markets around the country when, shortly after his 60th birthday, his employer of more than 30 years forced him out in favor of a man in his 20s. Before it became commonplace, he sued Conwed for age discrimination. When a judge finally got the case after many years of legal wrangling, he advised the company to settle because a jury would beat them on the merits of the case. Doom received his back pay and a lot of satisfaction from the decision.

By then, he had moved on to selling carpet at a retail store close to his home. He would walk the 5 blocks to work, carrying his lunch. He always brought a little extra so he had some to share with the young guys working there who didn’t plan ahead like Doom or didn’t have the money to plan ahead.

Even though there was no prestige and he was off the career track, he enjoyed the job. He was still selling, which he was good at, and there wasn’t as much pressure to meet quotas. He liked being a mentor to the other employees, most of whom were unskilled laborers, and with the modest money he made, he liked to spoil his grandkids.

Guys like Doom are not pull-a-family-out-of-a-burning-building type heroes. But steady, there-for-you-every-day heroes. He was the type of guy our society needs and depends on to be the foundation of their generation and give a boost to future generations.

I long ago realized I was lucky not to have some of my friends’ dads, even those with high-powered, high-paying jobs who left behind trust funds: dads who drank too much, yelled too much, hit too much or were gone too much.

And I was certainly lucky not to have Mickey Mantle as my dad. I know how to hold my fork, I take my hat off when I enter a building, I stand when someone new enters the room and I eventually became the student I was supposed to be.

As much as I liked to watch Mickey Mantle play baseball, he was nowhere near the role model Doom was.

Next week: Chapter 10: My First Official Girl Friend

Categories: My story

Loved reading this. Your Dad and mine were similar in many ways, although I suspect my Dad may have been quieter. Dad was in the Army and served for more than two years in northern China in the signal corps during WW II. He never talked much about, mostly because it was just something he did but it wasn’t a huge part of who he was.

We had proper manners at the dinner table, for example we had to ask to be excused after dinner before we could leave. And, my folks insisted on the proper, polite way to answer the phone: Hello, this is the Brockman residence. I’m Cliff Brockman. Who would you like to speak with? 😀