(I skipped over a few chapters, a few stories and my entire senior year to publish this chapter during the 50th anniversary week of Woodstock. Chapters 18-23 will appear at a future date.)

It was another one of Bob’s schemes. In the early summer of 1969, just after we graduated from high school, he saw an ad in an underground newspaper. More than 30 bands and artists were going to appear at a three-day concert in August in the countryside of upstate New York, at a place called Woodstock.

The ad promised a lot of well-known performers, from folk to rock: Joan Baez, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix, The Dead, Country Joe and the Fish, Arlo Guthrie and several others.

But also unknowns like Richie Havens, Mountain, Melanie, Joe Cocker, Santana, Sweetwater and several others. A Crosby, Stills and Nash was listed. We’d heard of David Crosby from the Byrds. Stephen Stills from the Buffalo Springfield. And Graham Nash from the Hollies. Were these the same guys? What would that sound like?

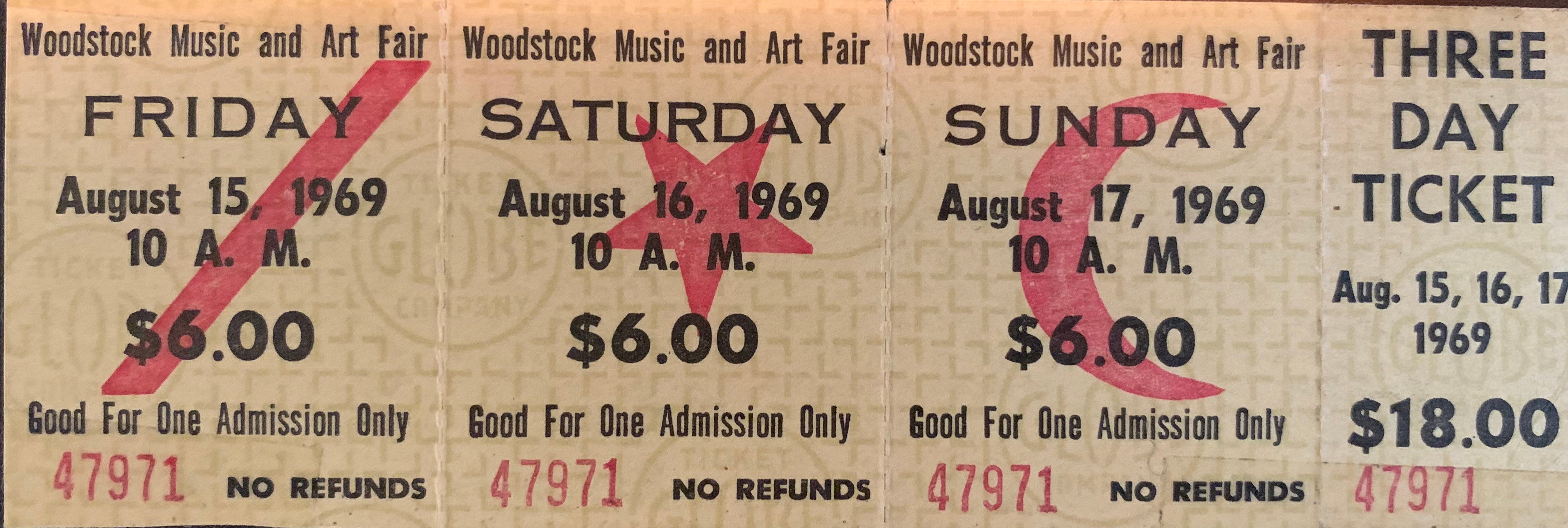

Still, we figured there were enough headliners to make the trip worth our while. Free camping. Just bring coolers and sleeping bags. All for $18.

Bob and I spent the last half of summer planning and preparing and when Friday morning, August 15, 1969 arrived, despite being 18 years old, we, along with our friend Sam, had no trouble getting up and getting out of town at 5 a.m. We figured it was only a two-hour drive so we thought we were leaving in plenty of time. We’d be there by 7 and be able to find a great spot in front of the stage.

The highways in western Connecticut were practically empty. We saw only an occasional truck making up for lost time or an overloaded family station wagon getting a head start on a vacation. We sometimes spotted a car similar to ours: Two or three young people jammed into a 1965 Mustang, trying to see past the sleeping bags. This sight began to grow more common as we crossed into New York State.

Still, we didn’t think much about what lay ahead. We were making good time. We had our tent and sleeping bags, of course, but we also had two coolers: one filled with a weekend’s worth of cold beer and soda and the other filled with food . And we had a hibachi and charcoal and various canned goods. We’d been camping before. We had planned this trip for months. We weren’t going hungry.

We finally realized what we were in for when we got to within 2 miles of the concert site and traffic slowed on the interstate and then completely stopped after we exited. There were no side roads to escape on. We were stuck. I suppose we should have been suspicious when we saw cars parked along the Interstate. It had taken us 2 1/2 hours to travel the first 140 miles. It took us five hours to travel the last mile to a parking spot. We were still a mile away but it seemed like 10, lugging those coolers and our gear.

Our friend Fred had left the previous Tuesday, which we thought was absurdly early. It wasn’t, as we’d soon learn. Fred, it turns out, was one of the first to arrive at Woodstock and spent the entire week in his sleeping bag in front of the stage. He didn’t get back to town until the following Wednesday.

I was beginning to panic about finding tickets. Then I saw a sign in front of a non-descript, middle-class-looking house advertising tickets for sale. And it was a middle-aged, stay-at-home mom hawking the tickets. Really? But I didn’t think I had much of a choice. I had to buy. This thing could be sold out.

Tickets in hand, we decided maybe there was nothing to panic about. Still, we decided to stop in a store and get even more rations and ice, just in case. By the look of the situation, we figured, there soon might not be anything left to buy.

The sun was at its August zenith as I stood in line outside the small grocery store for more than an hour. Inside, it was like the old woman in the shoe – the cupboards were bare. There was nothing. We would have to make do with what we had brought. We didn’t know at the time we had more than most people. Way more.

We had no trouble finding the festival. We just followed the constant stream of young people marching down the dirt road toward the festival. And that walk brought one cultural revelation after another. We thought we were worldly-wise 18 year olds. We weren’t. We were just a couple of months removed from our former identity as high school athletes. We were seeing people in stages of dress and undress we had never seen in our fairly buttoned-up hometown. And the hair. Our parents had convinced us that the Beatles had long hair.

At one point, we found ourselves walking behind this creature with a thick head of gorgeous blond hair, cascading down to her waist. We walked along, mesmerized by her beauty. We were trudging along, three abreast, lugging our coolers and camping gear but this heavenly vision perked us up and we glanced at each other and smiled. Maybe this walk wasn’t so bad.

At one point, the blonde shook her head, perhaps to avoid an annoying fly. As she did, her hair moved and we realized we could not see a strap across her back! She was topless!

We looked at each other and with just our eyes, agreed that we needed, despite our load and weariness, to walk a bit faster so we could pass her.

It was a lot of work, battling our bulky coolers and the crowds, but we managed, with great effort, to get past the object of our desire. Now we had to be real casual in turning around. Everybody was being so cool about everything. And we didn’t want to scare her off with our stares. Finally, we couldn’t take it anymore. Bob snuck a peak first, of course, and then started laughing. It was such an unexpected reaction that I gave up any pretense of sneaking a glance and just turned and stared. Our she was a he. And he was sporting an equally thick, luxurious, blond beard.

There were hills on either side of the road. On one side was the concert area; on the other were the campsites. While most of the parade headed straight to the concert area, we decided to set up camp. Lucky for us: Our tent site turned out to be closer to the music than we could get when we were in the concert area.

After Bob, Sam and I set up the tent and stored our gear, we made our way to the concert area. My $18 tickets were worthless. Several thousand people had trampled the admission gate and the announcer was saying in a slow, nasal, hippie speech, “It’s a free concert, maaan!”

We moved with the flow of the crowd to the back of the concert area. People lounged on blankets, waiting for the concert to begin. We were so far from the stage that, while we could see it, we couldn’t see the people on it.

We thought about trying to get closer. It’s always possible to squeeze one more blanket in at a concert. But by the time the music started, it looked like all the squeezing that could be done, had been done.

So we walked away from the music, up the hill. The intense crush we had been in all day made us grateful for the relative peace and quiet. We walked by hamburger stands, long since emptied by the crowd. We walked farther and farther up the hill. We could no longer see the stage, but we could see the towers and hear the music just fine.

The crowd kept growing. It seemed as if every American under the age of 25 was sitting in Max Yasgur’s farm. It wasn’t long before the sea of people swelled up the hillside, like a tide coming in, and swallowed us up.

I was wedged next to a guy with a grocery bag of marijuana. He was bagging nickel ($5) bags. I guess he felt a kinship with me, being squeezed so close for so long, so he offered to share. Trying to be cool, I told him I had plenty, thanks anyway.

Richie Havens opened the concert, hours late. He wasn’t a rocker and wasn’t well-known. But at least the concert had finally started and he played with such energy, he won the audience over, especially when he got to the last song of his set, “Freedom.”

Then Swami Satchidananda gave the invocation. Even though he was only on stage for about 10 minutes, it seemed like longer. We had come all this way, put up with all these people. We had come to rock, not pray. And besides, we were still bitter about the Beatles and their breakup with their spiritual guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. And this guy wasn’t even him.

There was a smattering of boos.

We stayed at the festival for the next acts: Sweetwater, Bert Sommer and Tim Hardin.

Then Ravi Shankar played his sitar. That was hard to sit through for the crowd of rock and roll fans. The audience was polite, for awhile. Not long into his act, there were some boos. And that’s also around the time the first rain came.

It was just sprinkling at first, but we decided we could see as well from our tent on the hillside behind the stage as we could from a half mile in front of the stage. The sound system up to that point was excellent and we’d certainly be able to hear it. As we got up to leave, it turned out, thousands of others had the same idea. At the same time. After all we’d seen that day, we hadn’t really realized the magnitude of the crowd until we tried to go where we wanted to go and couldn’t. There was a moment of panic. Individually, we didn’t have control. The crowd had control.

As the sprinkles intensified, the crowd pushed harder toward the exit. There was almost no air to breathe and my feet barely touched the ground. I prayed the rain wouldn’t come any harder. Any panic by anyone at that moment could have set in motion a disaster and the weekend would be remembered far differently than it is today. It was still just hours into the festival and all the “peace and love” that Woodstock has since come to represent hadn’t had a chance to wash over the entire crowd.

But amazingly, suddenly it did, as it seemed as if everyone realized we all had that same fear at the same time and a sense of peace ran through the crowd and everyone calmed down. And we flowed calmly off the festival grounds back to our tents.

My memories of that night are of the dark campground and the floodlights on the stage in the valley below, of Joan Baez’s crystal-clear voice singing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot ” and the world’s largest chorus joining in.

It rained overnight and when we looked out of our tent in the morning, we could see more people had arrived and we could see more people coming. Our modestly spacious site now had little room between tents.

Still, it looked to be a good day so we set up our hibachi and cooked breakfast.

Word was out in our camp area that we had food and drink so people kept approaching us for a handout. Some were pretty drugged out. They always had a compelling story about how long it had been since they’d eaten, but we were unmoved. We had come prepared. Why hadn’t everybody else? We had more than enough for three guys for a weekend, but we couldn’t just start handing it out. We couldn’t perform Jesus-like miracles and feed the multitudes. It’d be gone in minutes.

It was a bit annoying as people kept approaching us for food, but we managed to send out enough of a high-school-jock vibe to keep the beggars at bay.

We’d heard there was a swimming hole nearby and after breakfast, we went looking for it. We found it just over the hill we were camped on. When we got there, Bob, Sam and I were about the only people with clothes on. And that didn’t last long. Some naked girl asked Bob for a bar of soap and the next thing I remember was Bob running naked toward the water.

Helicopters from the National Guard buzzed the swimmers and soldiers, armed with cameras with telephoto lenses recently purchased in southeast Asia, leaned out and took pictures. The swimmers unabashedly posed and waved for the soldiers to join in the fun.

After the swim, we headed back to our camp site. As we got closer, each step became more painful. We figure the thick grass was hiding some very sharp nettles. We couldn’t see them, but each step hurt. Strange that we hadn’t felt them on our way to the swimming hole.

When we got to camp, a guy in a neighboring tent approached us.

“Hey, man,” he began. “Something happened with your fire while you were gone. It exploded.”

“What do you mean, ‘exploded?’” we asked.

“Like …,” he paused, searching for the right word. “…exploded, man,”

I began to look around at the fire and at our tent. I noticed that the tent was covered in yellow flecks. They appeared to be flecks of corn. I had been the cook that morning. The menu had not included corn.

I turned to Bob and Sam.

“Did either of you put anything in the fire this morning?” I asked.

It was quiet for a moment. Bob, who at that point in his life had not spent much time in the kitchen, then admitted he had put a can of corn in the fire to warm up while we were gone. Unopened.

Sam and I stared at him. The can had heated and exploded, spraying corn and the embers of our campfire all over the surrounding area. I casually looked at some of the nearby tents and could see flecks of corn. And some very small holes created by the flying embers.

We stood silent for a few minutes while we wondered what to do. We were beginning to be worn down.

We felt trapped by the beggars at our door, the crush of people, the heat and humidity, the delays between acts, the lack of facilities and the prospect for more rain.

In addition, we figured we needed to move our camp site far from our current spot because once our neighbors realized why their tents were leaking, they were going to be pretty upset with us, despite all the peace and love being practiced that weekend. The fact that they were so stoned, we figured, gave us about an hour to make our getaway.

As we were packing up for our move, one of us, and I can’t remember who, suggested we pack all the way up and go home. Maybe we all suggested it at once.

We had plenty of food and drink. We had a pretty nice tent location and the best acts were yet to come. But getting caught in the rush for the exits the night before had spooked us. We could barely see the stage, much less who was on it. And with the August mid-day sun blazing down on the cornfields, Yasgur’s farm was like the YMCA steam room. We decided we had soaked up enough popular culture for one weekend.

And we weren’t the only ones leaving. Thousands were pouring out as thousands continued to pour in. We ran into some guys we went to high school with and they crowded into and onto the Mustang. Other festival-leavers perched on our trunk and hood for the long ride back to the highway where they had parked their cars.

We made better time on the way out of town than on the way in, but still, we poked along, braking constantly as still-arriving pedestrians crossed in front of the car. At one point, a young woman who danced naked in the street stopped us. We figured her venture to Woodstock wasn’t the only trip she was on.

A couple of good-natured cops gently tried to pull her out of the street. But just as they got her near the curb, she would break free and dance back into traffic. It broke the tedium of the tie-up. After about 10 minutes, the cops finally got a good grip on her and we broke free of that town and that festival.

It felt good to drive 65 again. I didn’t realize then that I had been at an event that would become a symbol for a generation. I just wanted to get home and take a shower. And, since it was Saturday night, do a little cruising.

The movie “Woodstock” makes the festival look like the Greatest Show on Earth. But the filmmakers took 3 1/2 days of footage and condensed it into 3 hours of highlights. No festivalgoer experienced what that film captured. The movie gets you up on stage so you can see the performers. Watching the music today in your home, you can control the temperature, you can hit pause and go to the bathroom or get something to eat. Those weren’t our options.

Yes, Woodstock was wonderful … as a cultural moment. It set a tone for tolerance and brotherhood that should be long remembered. It introduced us to some legendary performers and performances.

But it was also a wet, hot, muggy mess. If you’ve ever been frustrated at a crowded, sold-out stadium concert, remember that Woodstock was just like that, times 10. And when I think of the worst traffic jams I have ever been, I remember that the traffic jam at Woodstock was just like them all … combined. There was little food, few facilities and very little security.

While there definitely was a feeling of peace and love in the air that was almost visible, there was also a feeling of danger. One spark of panic and the peace and love could have disappeared in an instant.

I’m glad I went to Yasgur’s farm and I’m glad I left when I did. My only regret (besides not taking a camera) is that I was so naive when I went. I would like to have had the experience when I was mature enough to realize what the hell was going on. But then…I might not have gone.

Categories: My story

I love this Alan, k eep em coming

Thanks, Dave! I hope you’re doing well. Week after next (which will be the last chapter for this year), I describe a chore at the Dairy I’m sure you’re familiar with.

Sorry these are done for now. You need to figure out how to monetize your posts. Then you can quit teaching and live off your royalties 😀!

Thanks, Cliff. Actually, while I should quit now, I have two more chapters about ready to go so I am going to go for another two weeks. Maybe by the time I come back next summer with more chapters, I’ll have figured out how to make the big $$. But I doubt it.