The summer of 1968 – after my junior year – had been a good summer. Most of it was spent working at Lincoln Dairy where I got a lot of attention from all the college waitresses who had tried to reform Page, and I had a fine time with a steady, gorgeous girlfriend, even if we weren’t quite on the same wavelength. We didn’t always have to talk.

Too quickly, though, it was time again for football camp.

Before my first camp sophomore year, I remember thinking about how much fun it was going to be. Camp, not football. Until I went and found out what really went on there, I only heard the word camp. The word football didn’t register with me.

It would.

I had never been to camp even though I lived in a town where many sent their children away in the summer to camp. Head Football Coach Frank Robinson sent a brochure home describing a camp that featured activities such as swimming and canoeing that could be enjoyed, tucked in between the practices and meetings.

But I don’t know anyone in the entire history of Hall High football in those days who had the energy for any of those extracurricular activities. The coaches wrung you out. The only free time we had – and there wasn’t much of that – was spent sleeping.

We left on a Sunday in last week of August when the sun still maintained much of its summer power and we didn’t return home until the Saturday afternoon of Labor Day weekend. It was a grueling 7 days, jammed every day with cross country runs, wind sprints, repetitive drills, hitting, hazing, mildewy uniforms and endless meetings in a WPA dining hall made of perpetually damp, rough-hewn wood.

The days started with a warbling recording of reveille at 6 a.m. While still in our bunks, we could hear the needle drop into the groove over the camp’s loudspeaker and a few seconds of hiss and pop as the well-worn vinyl spun before the music started. We then had to pour out of bed, into our Chuck Taylors and race to stand at attention at the center of camp.

Coach Robinson, dressed in gym shorts and a T-shirt that looked as if they were freshly starched at a New York laundry, would stride into our midst like McArthur coming ashore. He appeared to have been up for hours and always had a broad smile as he knew he was the only person, coaches included, who wanted to be in that particular place at that particular moment.

You had to be in line up on time. No excuses. If you were a straggler, running down the rain-rutted hill to the center of camp, even just10 seconds late, Coach would smile and make some gentle remark. But that lateness for the morning gathering would be cataloged by Coach Robinson.

And later that day, when we were running wind sprints at the end of practice, Coach would let us know by a seemingly casual remark that he remembered who had been late to the morning lineup. He’d smile and joke about the latecomer’s speed during the drills or how much he was sweating. And that maybe a few more wind sprints were what we ALL needed and wanted.

Coach, in his subtle, not so subtle way, let us know that we were all paying for our teammate who was late to the morning lineup. We learned the lessons: We were all responsible for and to each other. And don’t be late. Nobody liked wind sprints.

After taking attendance, Coach Robinson blew his whistle and we were off through the woods for a three-mile run. Coach called it Burma Road, referring to the particularly harsh, enforced march during World War II. The significance was lost on high schoolers, 25 years removed from that war.

Later in my life, running that distance at that hour became a routine for me but this was before our generation began jogging. At the end of the run, we had to jump into the chilly camp lake to wash off and race back to the cabins to change for 7 a.m. breakfast.

After breakfast, there was about an hour until we had to put the pads on and warm up for practice from 9 to 11. Then we had lunch and quiet time, supposedly the time you might be out canoeing. Every year a couple of rookies would paddle out on the first day of camp, not realizing the fatigue that was coming. But they only went on the first day. After that, quiet time was quiet time. We got in our bunks and napped like kindergartners.

And just as we were achieving REM, the camp horn would signal it was time to get up and haul your tired and sore body down to the uniform room and put on pads and jerseys that were still damp from the morning practice. Then we’d hit the field again for another 2 hours in the blazing August sun – although the afternoon practice often ran a little longer – and then dinner and then meetings at night.

The meetings were almost as exhausting as the practices. We sat in metal folding chairs for an hour while the coaches excitedly diagrammed plays. We were all given mimeographed playbooks so we could follow along. The pages featured purple ink images of horizontal ovals representing each player for each play. Then lines were drawn where each player was to go on each play.

After an hour or so, the coaches could see we were fading. That’s when they brought out the bedtime snack: a couple dozen dried out grocery-store brand cookies and a 20-gallon pot of some kind of sugary, flavorless juice. We were never sure what it was supposed to be. Lemonade? Kool-Aid? We just called it bug juice because that’s what was often floating on top.

Then we headed back to our bunks, exhausted.

But that’s when the seniors, who knew from experience how to pace themselves during the week, started hazing the sophomores, requesting that they sing songs or dance with each other. If the entertainment value wasn’t judged to be high enough, the performers were doused with ketchup and mustard that had been swiped from the mess hall.

I managed to avoid getting picked on too much because a lot of the seniors were classmates of my brother and while they didn’t hang with him, they respected him. The hulking fullback, Rich, had been pretty good friends with Page in junior high and he watched out for me. And my cabin leader was a kid whose family was on my paper route and he got a kick out of me. Even so, I got a soaking of ketchup and mustard one night to prove there was no favoritism. I couldn’t eat either for about a year.

I had no stomach for the hazing when I was on the receiving end nor when it came my turn to give it as a senior. But it seemed as if some guys lived for their moment at the torturer’s controls and only came out for football for that one week in August when they would be all powerful. I may not have liked playing very much, but I did like what the pressures of football and the pressures of peers revealed about human behavior in our little high school Petrie dish.

I only managed one complete camp. That was my sophomore year. It was a bit of a badge of honor to make it through camp. The second year was when Page died and I left halfway through the week. Senior year, I hyper-extended my knee and had to miss a couple of practices in the last 2 days. But the worst part of football camp is that it signaled the start of the football season.

Sure, we were glad to be back in school and see all our friends and check out any new girls who may have moved to town, but it also meant for the next 3 months, the only free day of the week we had was Sunday. Every other day, we’d have to be in that locker room, putting on those stinky, damp pads ready to go out to hit or be hit. For a full two hours.

I longed for daylight savings time to end. Practices had to get shorter as the sun began to go down earlier and earlier. But Coach Robinson didn’t let up. Since the school was in the center of town, Coach figured once the streetlights came on, and he brought out his bag of brightly colored footballs, practice could go on. And on.

I was thrilled to have contacts my senior year so I could see the clock on the town hall tower to gauge how much longer the torture of practice would go on. Before, I had to squint hard or ask someone. Quietly. Out of the side of my mouth while keeping my eyes on whatever drill we were doing for the tenth time. The danger was getting caught asking because you were supposed to be so interested in what we were doing that you paid no attention to time.

I hated football.

I only played because of girls.

I figured it might up my chances with them. In those days, it was a very important line on your high school resume. Even guys not yet blessed with much personality or physical talent gained simply by being on the team. And you didn’t even have to have talent or even play in the games on Saturday. You just had to be at practice. Every day.

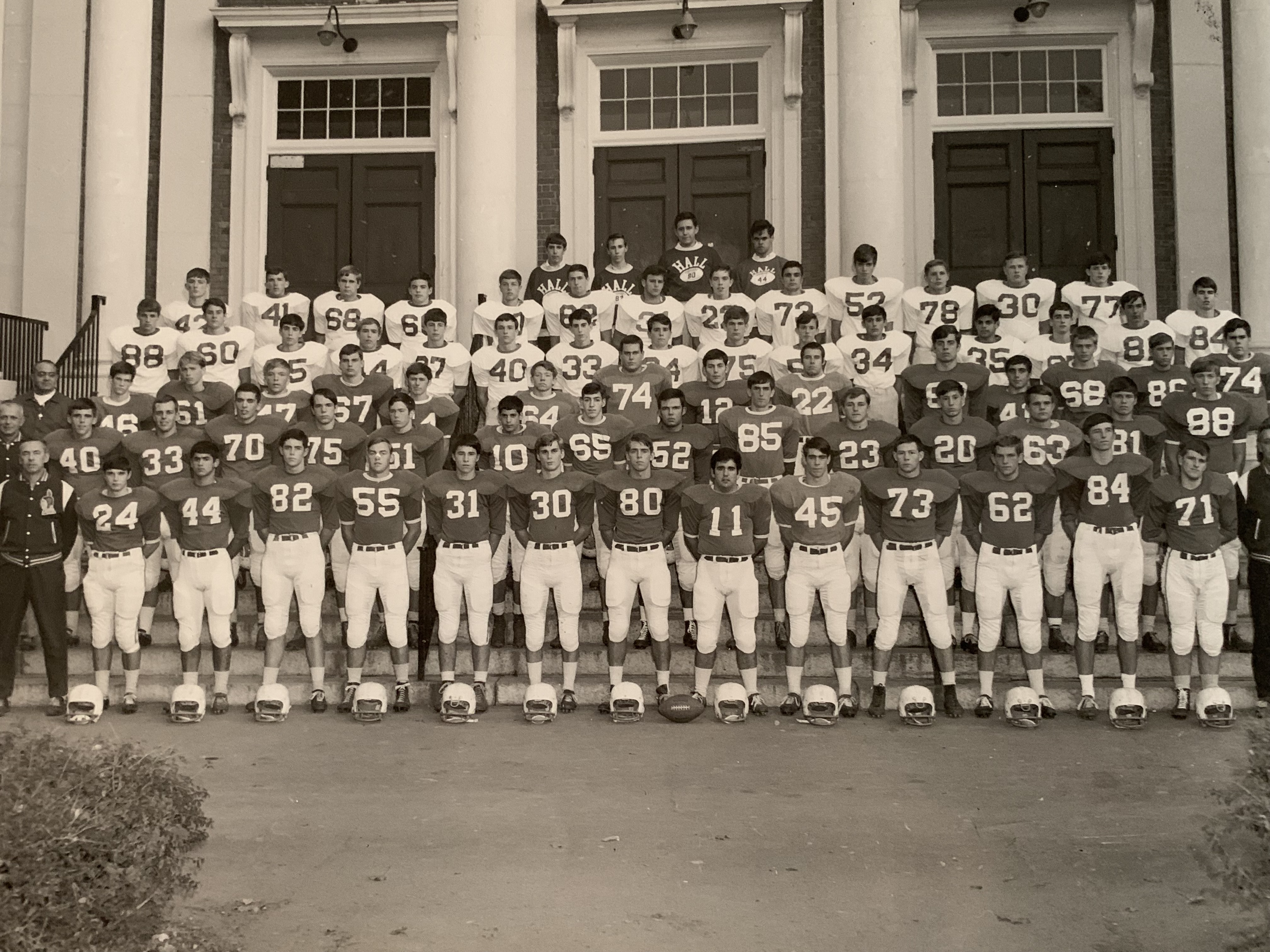

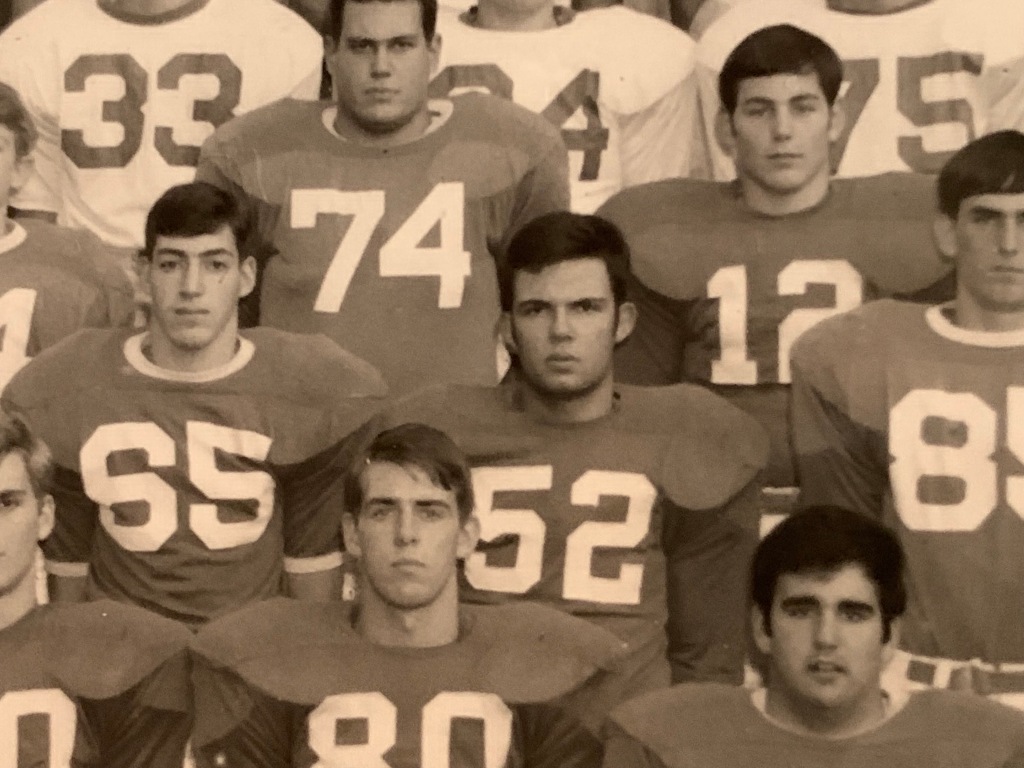

Because of my size – 5’ 8” and 165 – I played in the backfield as a sophomore. I actually had no idea what positions there were to play in football. Before heading up to school for my first practice, I asked Doom what position I should play. He had been a lineman in college and knew how little glory they got. So he told me to sign up for fullback.

But apparently, Doom hadn’t bothered to assess whether or not I might have talent at that position. Very soon, I was third string on the sophomore team at a small school. And if we had had a fourth string, I might have been on that. Not only was I slow but also, I was playing without glasses or contacts so everything was a big blur.

I’d run exactly where the play told me to go, whether there was anyone there or not. Frankly, I couldn’t really tell if there was a hole. It all looked the same to me and my depth perception wasn’t all that great.

In addition to being slow and unable to see, I had none of that athletic awareness that you need to be a good football player. The game is very disciplined in the design of the offensive plays and defensive schemes, but once the ball is snapped and everyone has done their initial job, the play opens up and there can be a million possibilities to consider in a split second. You need to react, not think. And you should especially not think about what you should be thinking. Which is what I often did.

One play clearly illustrates my football acumen. I was on the sophomore squad and to help the junior varsity team prepare for a game later in the week, we were running the enemy plays against them. Basically, as Coach Robby liked to say, we were live tackling dummies. Or another one of his favorites, cannon fodder.

One of the opposing team’s plays that we were running was really well designed, apparently, because even with my lack of speed and vision, I broke loose around the end. I had never felt so free on a football field. Usually I just went a yard or two and then everyone fell on top of me. But here I was, going around the end – untouched – prepared to run the length of the practice field. Even though it wasn’t a touchdown in a game, I could sense it was going to be something I would remember for the rest of my life.

Well, I do remember it.

As I turned the corner on daylight, doing all that thinking about what a special play this was going to be, I suddenly saw Don Kandarian, a very nice, affable guy off the field and a slightly crazed, very well-built defensive back, on the field. He was speeding straight at me.

I had about half a second to react. Rather than instinctively planning my escape, my reaction was: Wow! What is he doing there? How did he get here so quick? Should I try to run out wider? Or duck my head and try to …. Bam! Don Kandarian knocked the wind out of me. The best play I ever made on a football field came to a very sudden end. I was flat on my back struggling to breathe.

When I should have been reacting, I was thinking. And it wasn’t about football stuff. Or, more accurately, football stuff that could have saved me. It was an internal discussion about how amazed I was to see him and that maybe I wouldn’t get that touchdown and maybe I wouldn’t have much of a gain on that play after all.

I decided if I were going to survive three years of football, I needed to learn not to think.

Next week:

Chapter 19: I Can See Clearly Now.

Categories: My story

So glad you are back! Great start to more episodes. Thanks!

So good! Thanks for sharing!

Thanks, Hannah!

Welcome back!

Thanks, Kris. I hope you guys are well.

I was excited to see this was back. I enjoyed your latest effort. I never played football and had no desire to play. But I got a kick out of your description.

Thanks, Cliff. Glad you enjoyed it. It was the thing to do at the time. And … my lack of speed ruled out soccer and cross country. There will be a little more of it in the next two weeks, when I actually get into a game.

Great read. I bounced around to several schools and felt cheated at not going out for football. (I always missed ‘Hell Week”) sounds like it was no picnic.