The coaches could clearly see I was no running back. I had no speed, no athleticism and without glasses, could only see to the end of my arm. I did have talent for gaining weight so I was moved to the offensive line.

That was fine with me. All I had to do was take a couple of steps forward and hit the guy in front of me. Although, sometimes the coaches tried to confuse us with “blocking schemes.” That meant on some plays you didn’t block the guy directly across from you, but the guy to the left or right diagonally across.

While I had no trouble remembering baseball statistics, important dates in history and the names of every member of every band in the top 40, I often couldn’t remember which of the three directions I might go on a particular play. The secret codes inside the names of the plays just wouldn’t stick in my brain.

Still, I thought, it shouldn’t be too difficult in that both of us could only get up so much speed and hurt the other guy only so bad. As with so many other things about football, I was wrong about that assumption.

There are people who just exist on a different athletic plane than other people. Paul St. Onge, our captain, for instance. In practice, as I got into my stance across from him, I would analyze the situation. He was my height – maybe an inch taller – but he didn’t weigh as much as I did so I should be able to hit him with equal force and if I couldn’t knock him back, I figured I should be able to hold my ground. And if he hit me first, all things being almost equal, it shouldn’t hurt that bad.

I was wrong.

Paul played the game ferociously and hit you hard every single play, as if it was a Friday night fight after you danced with his girlfriend. I couldn’t understand where the power and fury came from. I couldn’t conjure it. But we knew, almost from the first day of practice on the first day of school, Paul was going to be our captain.

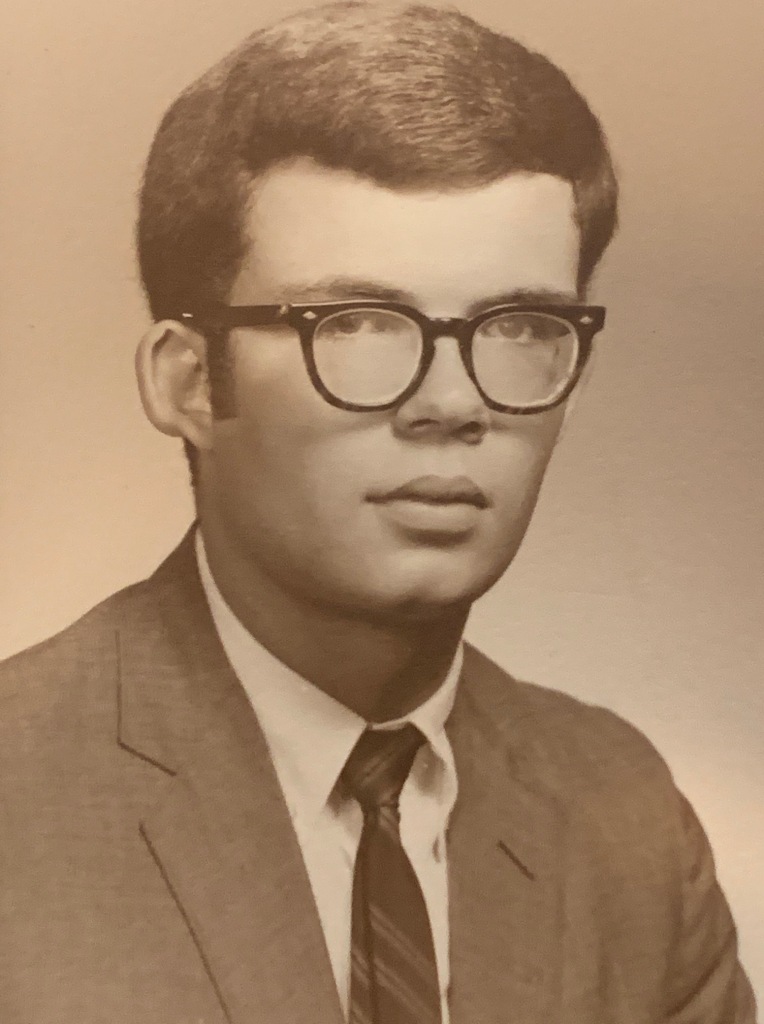

Even on the days I really tried, I couldn’t ring anyone’s bell. Still, I thought,maybe if I got contact lenses, it would help me in the two narrow concerns of my teen-age world: girls and football. Girls, because like every teenager who has to wear glasses, I thought the only thing holding me back from the opposite sex were my four eyes; in my particular case, my thick, tortoise-shell frames … chosen by my mother. Freed from those, I was sure to attract a greater number of the girls at school. Or at least one.

People often mock the idea that Superman could disguise himself simply by putting on some black-rimmed glasses. Not me. I bought it completely. I knew glasses could totally transform a person’s looks and life. I came to that belief after countless hours of staring into the mirror, studying myself with glasses and without.

With my glasses, I was a gawky, under-confident third stringer whose hair didn’t always do what it was told. Without glasses, I was instantly suave, my clothes fit better and I had the confidence of a first stringer. Of course, these realizations came to me as I was staring into a mirror … without my glasses.

And some of my visions may have been true. The glasses frames in those days were hardly fashionable. The choices ranged from the cats’ eye frames for girls to those that were – for boys – about as thick as a stout man’s belt. You could barely see a person’s face. Google images of Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly and you’ll see what I mean. By the time the Beatles came to America, John Lennon got rid of his glasses in favor of contacts.

In addition to needing them for my love life, I needed contacts for football because football is confusing enough when you can see with all those bodies running every which way. But when you are legally blind without them, it’s hopeless.

I finally had saved enough money to split the cost with my parents on a pair and I felt transformed. It was in the early days of contacts and the pair I bought were made of strong, rigid plastic. Although, even after a long break in period, they were just barely tolerable. I didn’t care. Too much. It was worth it because while my play may not have improved enough to cover the $300 cost of the lenses, I finally could see which coach was yelling at me.

Whatever my athletic improvement was, it wasn’t that great and it didn’t last long. Shortly after we got back from football camp, we were two hours into a practice on a field off to the southwest side of the school. It had been a dry summer, hadn’t rained in weeks and even though it was September, the summer heat had remained. The dirt on the field had been turned into 2 inches of a fine powder by our metal cleats.

Sweat was pouring off my brow into my eyes like a waterfall. My vision was blurry and I kept wiping, rubbing and blinking, trying to bring things into focus. As I lined up for the next play, just before the ball was snapped, I realized I had wiped the contact out of my right eye into the pillowy dust of the football field. I stood up just as the ball was snapped. Of course, I got creamed on the play because I was looking at the ground, thinking about the $150 lense that was down there.

At that moment, football mattered even less than it had before and I began screaming for everyone to move out of the way and began pawing through the dust. And of course, Coach Chalmers started yelling out me. He was running this practice, not me.

I told him about my contact and, as a parent, he could appreciate the cost, but he was not happy about moving his practice even a few yards away so I could look. Everyone knew my search was futile and after a few minutes, Chalmers was grumbling again about moving the practice back to his field, so I gave up the search.

Because I couldn’t afford the replacement cost, I played the rest of the season using just the left lense. And I went to my classes with just the left lense. Which may partly explain my not-so-great grades. And the headaches.

A few months after the football field incident, after I had managed to secure a replacement lense, around Christmas time, I lost my contact case. No problem, I reasoned. I was wearing my lenses and it was empty. It’s just a container. So is a glass. I tried to think of any possible downside if I put them in a glass and couldn’t come up with one. So I put them in a glass of water beside my bed. That was fine as I was the only one living on the third floor and the only one who was ever up there. Usually.

Once in awhile my mom would come up to gasp at what a mess it was. Although, if I got any warning such as hearing her coming up the stairs when the volume of my radio just happened to be down a bit, I heaved a bunch of stuff in the closet. Mom did try to come up the stairs slowly and clear her throat or cough loudly so she wouldn’t see anything concerning a teen-age boy she didn’t want to see.

But I hadn’t thought of every scenario.

The glass was sitting next to my bed and I was in the shower getting ready for a date. Just about that time, my 2-year-old niece, Jen, who didn’t yet understand the rule about not coming up to the third floor yet, came up to my room to explore. And while exploring my room, she got thirsty. And drank the glass of water that contained my contacts.

Luckily, I suppose, she only drank one. So it was a lesson for half the price. I was all for turning her over until the thing came out. Or feeding her laxatives. But everyone in the family got mad at me for my persistence about the matter. I couldn’t understand it. I wasn’t the one who just drank expensive eyewear. Jen had.

Contacts cost me a lot of money and grief over the years. Freshman year in college I woke up blind one morning. And it wasn’t the Moscow Mule I’d been drinking the night before, although it did play a part. I simply couldn’t open my eyes when I woke up. When I tried to lift my lids, I was in great pain and tears just started pouring out of my eyes. I was in agony. The RA had a couple of guys walk me over to student health where I sat for a couple of hours.

The folks there decided the case was too complicated for them. They made an appointment with an ophthalmologist in downtown Boston and put me in a cab and sent me on my way. The cabbie tried to cheer me up because he was sure he was meeting a guy on his first day of being blind. He helped me up the stairs and got me settled in the Dr’s office and wished me good luck.

A few minutes later a nurse led me back to the doctor’s office and all I could hear from the doctor was grave concern.

“Hmmmmmm,” he said as he gently touched my eyelids.

I could feel that his face was about 2 inches from mine.

“Oh, my my my my,” he exclaimed softly.

I couldn’t take it anymore.

“How bad is it, Doctor?”

“Oh, it’s bad,” he answered. “Very bad.”

“Will I be able to see again?”

“Well, I don’t know,” he said, not sounding hopeful and stretching out every word. “You might have to begin learning Braille if this doesn’t work.”

And with that, he pried my eyelids open and put a couple of drops of numbing solution in each eye and my eyes popped open.

“In the future, don’t leave your contacts in all night,” the doctor said. I could see him now and he was smiling. He had been through this before and had enjoyed scaring me. “You scratched your corneas when you did that. They should be fine in a couple of days, but I wouldn’t wear your contacts for a week or so.”

Looking back, maybe I’d have been better off if I’d just stuck to glasses. I’ve never had a problem with them that a little athletic tape and a black magic marker couldn’t fix.

I eventually gave up on contacts. When I was 50. After I got the girl of my dreams. And was pretty sure she wouldn’t leave me.

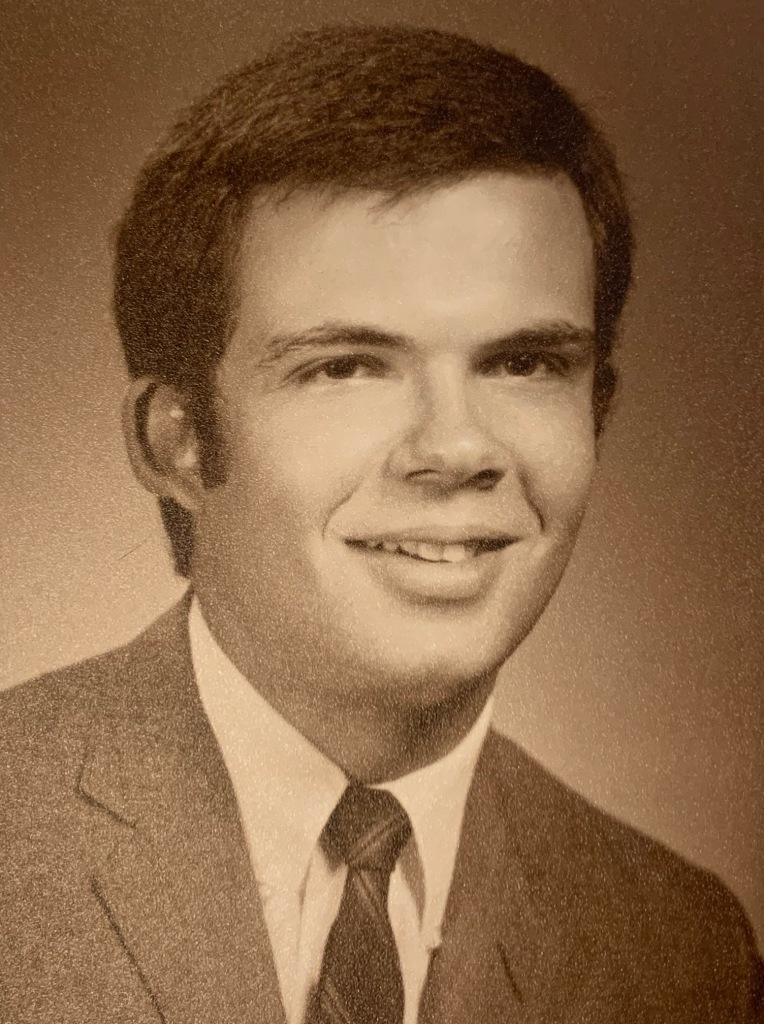

Being able to see what was going on during football led to a couple of good moments on the field senior year before I came to the crossroads of my athletic career. I weighed 180 pounds by then. I’d like to say the 15-pound weight gain since my sophomore year was muscle from time spent in the weight room, but probably 50 percent of the gain was beer.

I finally made first string and was starting at left tackle. I would say that was owed probably more to attrition than to ability. Not everyone could stand the tedium of three years of football camp and then three years of showing up everyday for practice. The 100+ kids who showed up for that first meeting in August before our sophomore year had dwindled to about 20 seniors.

My first big moment was when we were playing Hartford High in a preseason game. These city schools were big: lot of students and lots of size. When I ran out onto the field for the first series, I saw the guy across the line from me was as wide as two of our guys. He weighed over 300 pounds. My first starting assignment and I’m going up against a sumo wrestler.

The ball was snapped and out of fear, I tried to channel our captain Paul’s ferocity and, screaming at the top of my lungs, I drove as hard as I could into this guy’s stomach. I knocked him back 5 yards and as my helmet disappeared into his belly, I realized he had the build of the Pillsbury doughboy.

All game long, I kept driving him back at least five yards on every play. To the coaches, it looked impressive. It wasn’t. But I kept that to myself as Coach Chalmers smiled at me for the first time in three years. And patted my helmet after the game. Gently, this time.

My other moment came in our second preseason game. We were running a play and suddenly the ball popped out of the back’s hands and went flying. I was still holding my block and churning my legs as I had been taught the past three years when suddenly I looked down and saw the ball. It was right between my feet. And, just as I also had been taught, I yelled, “Ball!” and gave up my block and fell straight on the ball. I was suddenly at the bottom of a pile of the ten heaviest guys on the field. Until I had to give it up, I squeezed that ball like my 4-year-old self held my teddy bear.

“Fumble recovery by …,” the public address announcer paused as the refs untangled the pile of bodies. “Hultgren!”

What?

I looked up to the press box in dismay. The only time in my life that my name could be announced deservedly on a public address system at an athletic field. And the credit goes to someone else?

To make it worse, Doom was playing golf on the municipal golf course nearby and the hole he was on was near to the stadium. And he was playing with Hultgren’s father, who often bragged to Doom how good his son was and always asking if I had seen any “action” when he knew, up until then, I hadn’t.

When we both got home later that afternoon, Doom told me he heard the announcement of the fumble and how Hultgren’s dad bragged about it the rest of the round.

“But the announcer got it wrong!” I said. “I recovered that fumble.”

“Really?” Doom said. He and I both knew it was more likely that Hultgren would have recovered the fumble. But this one time I had done something right on the football field and I was the only one who knew it. Well, Hultgren knew it, but he wasn’t about to tell anyone. And he didn’t. Still, with two pretty successful games under my belt, I thought that I might be able to keep the charade of my football competency up all year.

But the real season – long and revealing – was about to begin.

Next week.

Chapter 20: The Crossroad.

Categories: My story

Good writing as always!

Thanks, Cliff!