Senior year started off going my way. I was recovering socially after the breakups with Bethani and then Annie. I survived the final football camp of my life. I had made the starting team and that meant something: getting presented at the beginning-of-the-year, all-school assembly.

We were announced individually and then jogged to about where our position would be if we were on a field and not a stage. The audience let loose when each player was announced, as it was the one school assembly of the year students were not overly monitored by the teachers.

The loudest cheers were for the best players, of course. The cheers for me were not at that level, but the sarcastic shouts from my friends kept me from an embarrassment of silence.

I didn’t care. I was on that stage. At that assembly. From the moment you saw that scene as a lowly sophomore, that became the dream: to be up on that stage and introduced as a starter. Except for the genetically gifted, it wasn’t easy to get there.

Sometimes, as an underclassman, you hit that point where you felt like the season, or your football career in general, had already gone on forever and yet forever was still in front of you. But the thought of standing on that stage for that brief moment of adulation in your senior year was enough to keep you going. Or at least enough to keep you from not quitting at that particular moment.

Once on stage, all the guys on the team stared straight ahead. We tried to look as if we were about to run out on the field for our biggest game of the year, rather than, in a few minutes, heading to 3rd period algebra. I wanted to look as big as an offensive left tackle for a small suburban school could look. So for a few days before the assembly, I practiced puffing my chest out and trying to keep it puffed out for the three minutes we would be on the stage. Without it looking like I was puffing up.

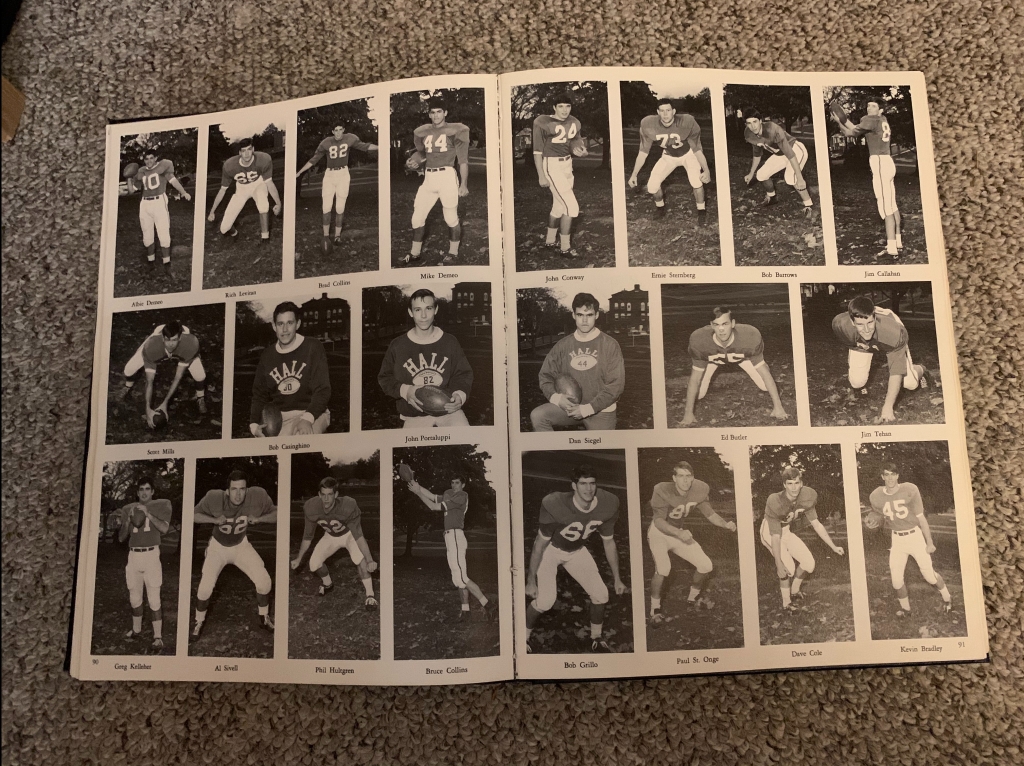

The other big moment for seniors on the team was the yearbook picture. Yes, just like all the other school sports, the yearbook featured the write-up about the season, the obligatory team photos and the random action shots. However, football was the only sport that featured all the seniors – starters and scrubs and the team managers – posing for individual photos in a special two-page spread.

This was a huge deal. Bigger than appearing at that ephemeral school assembly that only the players would remember. These individual pictures would be in the yearbook forever, for everyone to see. As sophomores and juniors, whenever we had a free moment, we’d repeatedly talk about how we were going to pose when we got to be seniors.

Often, guys would strike potential poses when we were changing in the locker room, asking for feedback. Or it would be a topic of conversation on a bus ride home after a game, if Tommy McLoughlin weren’t singing every word of Arlo Guthrie’s 22-minute long “Alice’s Restaurant.” But fun and talking were only allowed if we won. When we lost, it was quieter than a Catholic Church in the suburbs. We were taught to be silent, to be sad and mad and to reflect on why we lost.

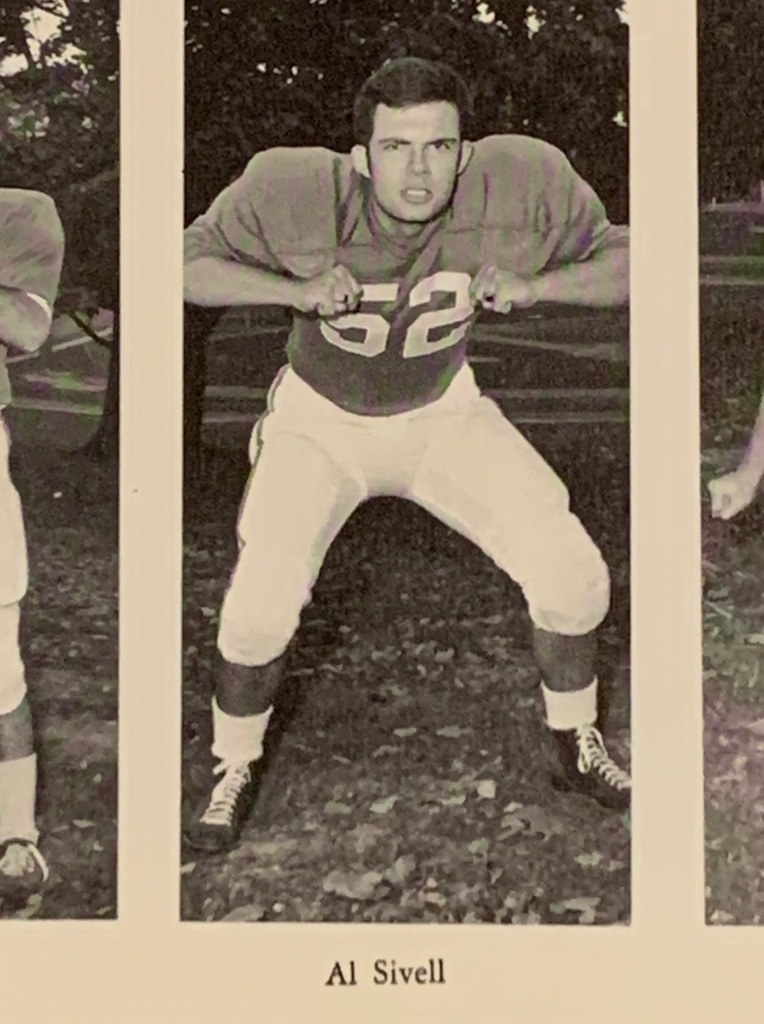

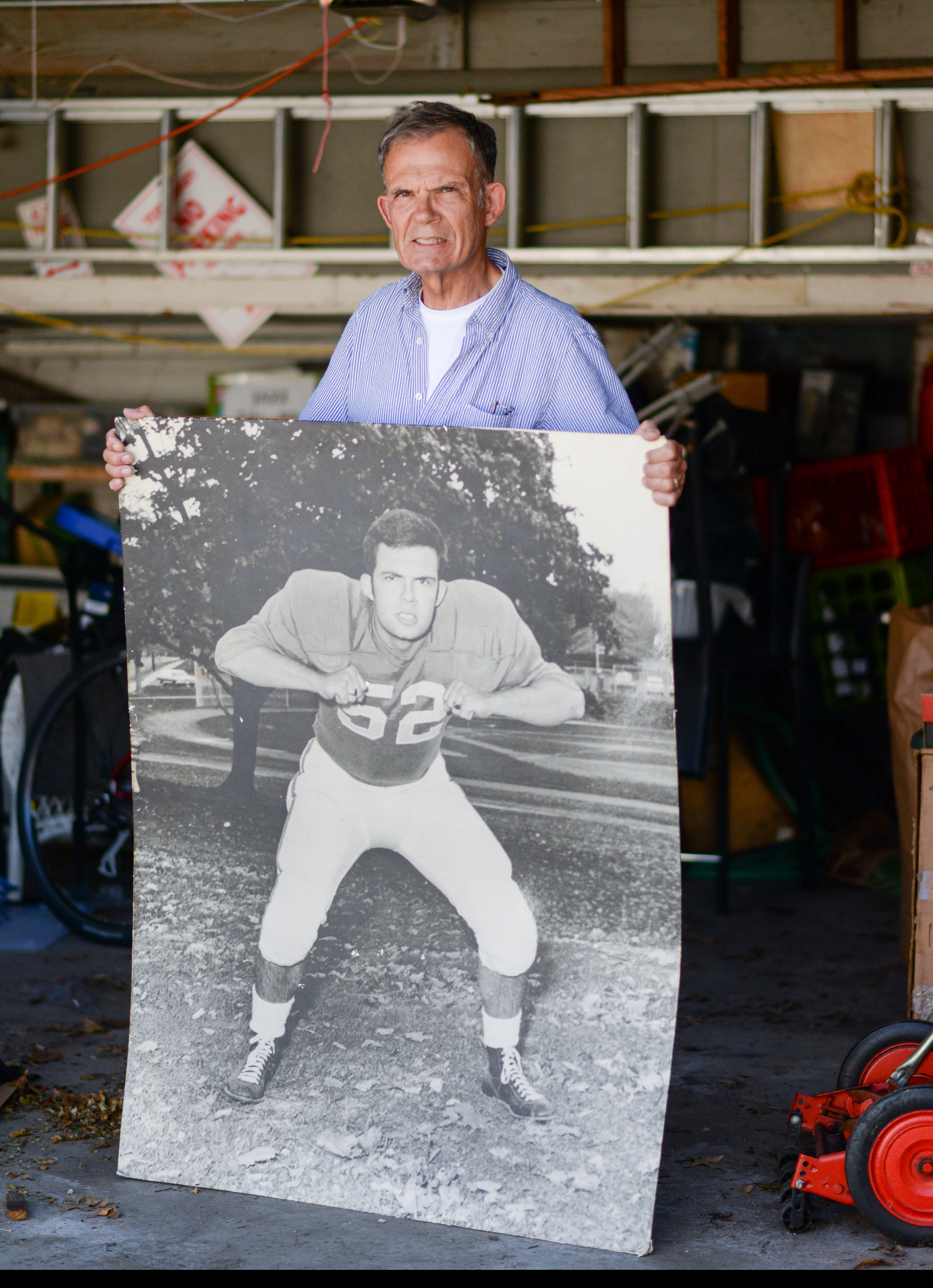

Running backs had a lot of cool poses to choose from. But not lineman. Previous yearbooks, which we studied for inspiration, showed most of them down in a four-point stance, looking up at the camera. Even if you were a good football player and a good-looking guy, you didn’t look good in this pose. You had no neck. It was as if your head had been pasted to your back in an awkward position.

I didn’t want that for my journey into Hall High School posterity. After a lot of time and thought, I hit upon what I thought was the best pose I could hope for as a lineman. In a game, after the ball was snapped, my job was to put my helmet in the chest of the defender. That meant I was somewhat upright and I didn’t have to do that stereotypical lineman pose, being down, but looking up.

As picture day approached, I spent a lot of time in front of the mirror – more than usual – searching for that perfect facial expression that said I took football and the school’s tradition seriously, but also let people know that I didn’t take them too seriously. It was a fine line to walk, but on the eve of picture day, I finally had the right expression and I had practiced it enough that I was sure my facial muscles would remember it just as the picture was snapped.

On picture day, while the underclassmen were beating each other up at practice, we seniors put on our freshly laundered, home game uniforms and went with the photographer to a shady spot on the northwest side of the school. One by one, the photographer called the guys up for their immortal pose and one by one, they revealed the poses they’d been practicing for three years.

Finally it was my turn. By then, all the guys were critiquing the poses, commenting on style and degree of difficulty, as if they were judges at an Olympic ice skating competition. As I was about to get into my pose – which I had kept secret for fear of imitators – the guys were giving me suggestions.

My attention turned to them for a moment and since I had what I often coveted – an audience, I momentarily forgot about the photographer and focused on the guys, trying to make them laugh.

“Maybe I should pose like Scott,” I said, referring to our teammate who psyched himself up for every play, be it in a game or at practice, by growling loudly.

“Grrrrrrr!”

The guys laughed. I succeeded.

Click.

“Next,” the photographer said.

“What? NO! I was imitating Scott,” I said as I pointed at Scott who didn’t always get our jokes, but sensed this one was on me and he was enjoying it.

“I wasn’t ready!” I pleaded with the photographer.

But he said there were no do overs.

My moment of football glory captured in amber was a joke. Lord knows, I was always up for a joke, but not one that would be frozen in time. Not one that did not reflect my personality in the slightest. Or my feel for football. Not one that I felt needed explaining.

The last picture taken, we went back to the locker room, changed into our practice gear and slowly jogged to join the rest of our teammates. I knew that picture would come back to haunt me. But I didn’t realize it would still be with me, more than 50 years later.

Before we knew it, it was Hell Week. Hell week is what Coach Robinson called the week before we played any tough team and there were at least three Hell Weeks during each season. Most weeks of practice were hell, in my opinion, but during “official” Hell Weeks, the coaches ratcheted up the intensity of the drills, the barking of their instructions and their looks of disappointment.

Hell Weeks came the week before we played Weaver, an inner-city school, at the beginning of the season; and the week before we played the farmers from Windham in the middle of the season; and the week before the final game when we played our cross-town rival, Conard.

Weaver was usually our opening game. It was a team from Hartford that was out of our league in more ways than one. We played in a small city/suburban conference, while they played big city schools. They had some very big and talented players. We were a bunch of skinny kids from a very small school. Once in a while, say every two or three years, we’d get a kid who weighed more 200 pounds. Mostly, though, we featured a line of 160-180 pounders. But our coach scheduled the game early every year to toughen us up.

The toughest drill of Hell Week came right after warm-ups on Monday. It was called Crossroads, an open-field tackling drill. Coach Robinson would rub his hands together and grin maniacally anytime he or anyone said “Crossroads.” Kind of like a teen-age boy using or hearing the word intercourse in any context. Everyone dreaded Crossroads, except for the few psychos who loved to hurt and get hurt.

We formed two lines, facing each other, destined to meet at a particular spot that Coach Robinson deemed The Crossroad. One line was loaded with linemen and defensive players. The other with guys who handled the ball. The guy with the ball would start running as hard as he could straight at the opposing line. And you, in the other line, would start running, ostensibly as hard as you could or dared and the two of you would meet – at The Crossroad.

The idea was to teach the ball carriers how to take a hard hit and not fumble and for the guys on the other side how to deliver a hard hit and perhaps cause a fumble.

Coach would watch the drill to see the hit, but mostly he was listening for the sound of the hit. He wanted a particular pop and it had to be at a certain decibel level. If he deemed it loud enough, you could head over to the practice field. If not loud enough, you had to get back in line and go again.

There was no attempt to evenly match the opponents so as you got closer to the front of the line, you kept leaning out to count and recount the other line to see who you matched up with. After two plus years and hundreds of drill with these teammates, you knew how hard each one of them could hit. And how much pain they could deliver. There were guys you definitely wanted to avoid.

Sometimes Coach Robinson would see an obvious mismatch at the front of the line and he would make a quick switch. But other times he would just rub his hands together and relish that mismatch, especially if he thought one of the players involved needed a wake-up call.

After warmups on this fateful day, I jogged over to where the drill lines were forming and got in my line. Soon it was my turn. I was pleased to see that my opponent would be a third string running back. He wasn’t too big and he wasn’t too fast. He ran at me at about 3/4 speed and I ran at him at 3/4 speed. I made a clean tackle and he held on to the ball. We bounced up, ready to be sent on down to the practice field.

It had been the picture perfect Crossroads. It looked good. But, because neither of us had run at top speed, it didn’t have the sound that Coach wanted. So we were told to get back in line and do it again.

Since there were fewer ball carriers, their line was shorter and if you had to do the drill twice, you never went against the same guy. So I leaned out of line to see whom I was going up against this time. I recounted, probably a dozen times.

No.

It couldn’t be.

Barney.

Actually, his name was Greg Kelleher, our quarterback and co-captain. We called him Barney – and still do – because he reminded us of Barney Rubble. He always needed a shave, even 5 minutes after his last shave. And he was about 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighed 200 pounds. He was a human bowling ball.

In addition to his throwing and running abilities, his build was an asset. There was no good way to tackle this guy. There was no way to knock him over. If you ran straight into him, you would just bounce off. You couldn’t hit him high, because there was no high side to him. If you tried to hit him low, it felt as if you were trying to tackle tree trunks. There was no upside for me in this match up.

I tried to stall and let the guy behind me pass me. But this wasn’t like a line for a free bag of food at Howdy Beefburgers. No one wanted to pass anyone. And the guy behind me had leaned out and he certainly knew whom I was matched up against.

Of course, the line moved quickly and too soon I was at the head of the line. Barney’s was grinning at me. I could make him laugh in the classroom, which was OK. I didn’t like the fact that I made him laugh on the football field.

Barney didn’t mind Crossroads because of his physical advantage. Actually, he seemed to take a perverse pleasure in the drill. He looked across the field and saw me and knew he wasn’t going to get hurt. His only concern was that he might have to go again because I surely wouldn’t hit him hard enough to make the pop loud enough.

Barney started running. And I started running. I was sick of running the drill and on my way to meet Barney at The Crossroad; I decided to just let it rip. Hold nothing back. If I popped Barney loud enough, coach finally would let me on the field and I’d be done with it.

As I got near Barney, I realized I was exceeding my personal speed limit and was a bit out of control. My head was bouncing up and down as I tried to pinpoint my target. I began to lower my shoulder and my body while trying to keep my speed up. We’d been taught that the ideal tackle was to put your head on one side of your opponent’s thigh and wrap your arms around his legs and keep your feet moving and drive him to the ground.

But we were running at top speed and I slightly misjudged where my shoulder would hit his legs. Instead of his thighs, the sharpest point of his hips hit the sharpest point of my shoulder. We made a loud bang! It was definitely loud enough for Robby to grunt a laugh of appreciation and grant us entrance to a 2-hour practice full of more hitting.

But I wasn’t going anywhere. I was on the ground in agony, writhing in pain at The Crossroad. Something was wrong with my arm.

People were shouting at me to get up, but I couldn’t, so they moved the drill over a few feet and kept on running Crossroads. Coach Robinson came over, looked down at me and asked what the problem was.

“I can’t move my arm,” I groaned. It was the strangest sensation.

Coach looked at me, then my arm. Despite my pain, I could see in his eyes, he was making a decision to do something. Before I could protest, he grabbed my arm, and ignoring my screams, he twisted it and gave it a shove. I could hear it – and feel it – distinctly click back into the socket.

“There,” he said. “You’re fine. Get over to practice.”

“Good hit,” he added.

The excruciating pain was gone as was the weird feeling of not having any control over my arm and hand. But a dull ache in my shoulder remained. Still, I did as I was told and endured the entire two- hour practice. I got yelled at a lot that day. Apparently, I wasn’t getting my right arm up and that’s why the defense was getting by me.

No kidding.

Toward the end of practice, Coach Chalmers – who had been down on the practice field and didn’t know about what happened at Crossroads – was so mad at me, he had someone challenge me for my starting spot. We went one on one and I had to keep the lineman on the other side of a line for 5 seconds. I still couldn’t raise my arm much above my waist but I compensated by overplaying that side so the defensive guy would go the other way to my still working left arm.

Chomps – which is what we called Coach Chalmers behind his back – was still mad, but grunted approval that I could get the job done if I was so determined. The pain was so fierce, I guess it made me fierce.

I went home in terrible pain. I didn’t tell my mother what was wrong. She wasn’t in favor of football one bit. You got hurt playing football. Mom grew up in Brooklyn and in a world of women, tailors and dressmakers and didn’t have much contact with football or football players.

I wanted to tell Doom what had happened. Doom knew and loved football. He’d had been a co-captain of his college team. But he was no fool about it, either. He knew how dangerous the game could be.

When all the other kids were signing up for peewee football, I wanted to sign up too. I figured it was going to be just like baseball. But Doom refused to let me play until I got older. He said that it was a hard game and people got hurt. And it was one thing to get hurt at age 10 and another when you were in high school.

When Doom got home, I was already in bed, not asleep, but crying in pain. The next day we went to the orthopedist. The doctor said I had stretched a bunch of ligaments and it would have been a whole lot better if I hadn’t practiced after it had happened. He wrapped me in a lot of tape and gauze, immobilizing my shoulder and my arm, kind of like a body cast without the plaster.

I had to go back twice a week for four weeks and have it rewrapped. I was out until the Windham game. I was a bit disappointed. Not that I’d be out for four to five weeks, but because the doctor said I’d only miss half the season. I figured I was done.

At first, I still went to practice every day and watched my teammates run the repetitive drills. I stood on the perimeter of team huddles and meetings. But I began to feel myself separating from the team. I wasn’t a player anymore. The team managers had a purpose. I didn’t. And it was one thing to participate in the tedium of practice. It was another to just stand around and watch it.

So I began skipping practices. The fall weather had set in so I spent several afternoons a week driving around. Sometimes with my friend from the rival high school, Dave Armstrong, who had a 1956 Chevy.

If Dave wasn’t around, I drove myself. It was a bit challenging as I had a 1962 Oldsmobile F-85 with 3-on-the-column shifter and it was my right shoulder that was wrapped tight to my body. Only my right hand, which poked through an opening of my shirt near my belly button, could move.

So I learned to drive shifting with my left hand. It didn’t look especially cool and it wasn’t especially smooth. And it was a bit dangerous when I wasn’t on a straightaway. But it was a lot cooler than walking. I would hold the bottom of the wheel with the right hand of my incapacitated arm and then reach through the steering wheel with my left hand and shift. It really wasn’t that hard.

The only hard part was turning and shifting at the same time. As I approached a turn, I had to slow way down, to about the speed of someone driving from their nursing home to church on Sunday morning. I’d push in the clutch, quickly reach through the oversized steering wheel to the shifter, down shift, and then quickly pull my arm back through the wheel so I could use it to turn the wheel. Once I was through the turn, I released the clutch and gave it gas.

People honked a bit, but no more than they honked at my mother, who always drove under the speed limit.

“That’s the limit,” she would explain. “Not the speed at which you’re supposed to drive.”

I told my mom that my arm was good enough to shift, although that would have been physically impossible if she wanted to think about it. But she didn’t. She was no fool, but she didn’t say anything.

I was out for five weeks. When I was cleared to play again, they had to shave my chest and tape me every day before practice. By that time, the energy I had mustered to be a starter was gone. I was ready for the season and my football career to be done.

I was a member of the team and got to wear my team sweatshirt to school on the Fridays before a game, but I had lost my starting job and wasn’t going to win it back in the weekly challenge drills. I didn’t have the fire and frankly, my arm still hurt so I wasn’t going to risk it. I did get sent into several games in a mop up role.

We were pretty good that year, only losing the two games we were expected to lose although it wasn’t quite the success we had hoped for. The year before, we hadn’t had the greatest team, but we had some magical spirit when it came to important games and pulled off some big upsets, especially the last game of the year against our archrival and knocked them out of the championship.

But in our senior year, when we had a more complete team, we couldn’t duplicate those miracles. After we lost our last game, against our archrivals, a lot of the guys were crying in the locker room because the football season and their high school football careers were over.

But I didn’t cry. Not even close. I wanted to shout for joy.

Next Week: A special edition. I’m calling it Chapter 10A. Because it follows up on Chapter 10, A First Girlfriend. I recently found a note from that first girlfriend. Bethani wrote it after we’d been dating for six months. It provides her perspective of our relationship. Apparently, I was not the perfect boyfriend. Rather than starting “Dear Alan,” her note starts with “Look, Creep!”

That’s next week.

Categories: My story

Another Covid week behind us; saved by your post. So sorry your senior football picture was spoiled. Maybe you could strike the mystery pose and have Susan capture that Sivell magic.

Looking forward to the next installment.

“Crossroad”? “Hell Week”? No kidding. Those coaches would be canned today and it’s a miracle you didn’t suffer permanent damage from having your arm yanked like that and encouraged to continue practice. We all know football is a rough game but that old “Rub some dirt in it and walk it off” treatment is gross negligence.

Never knew you were a jock! I tried out for the basketball team in HS. But, I wasn’t very good and didn’t make the cut. I gave up my dream of wearing a letter jacket.