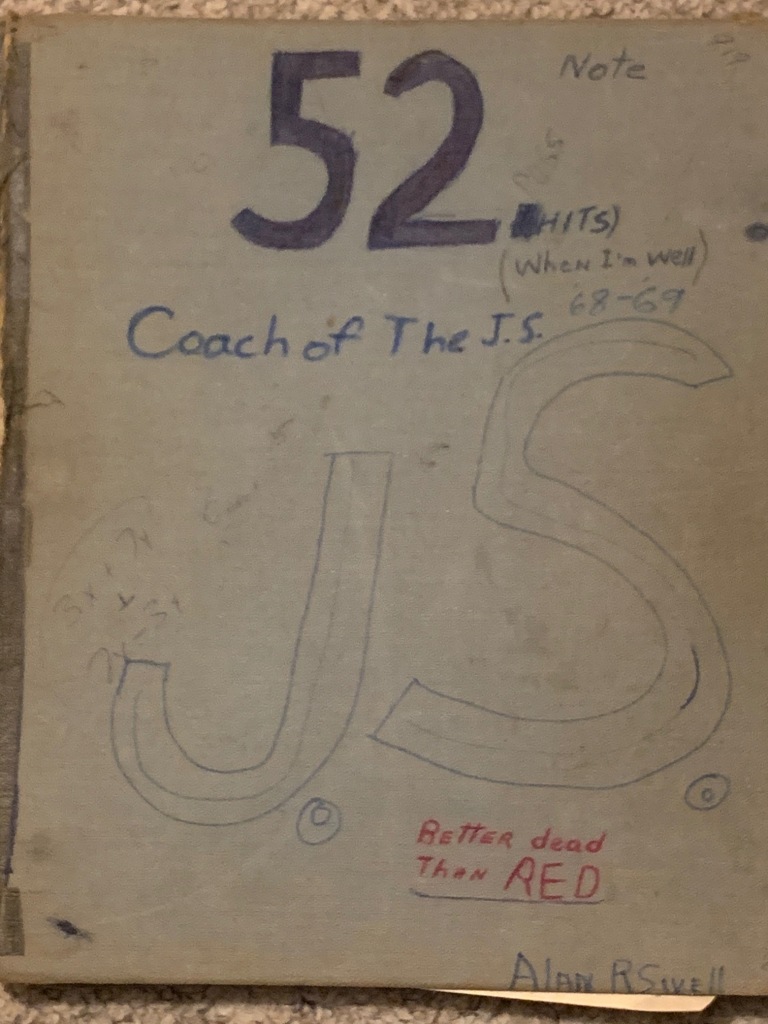

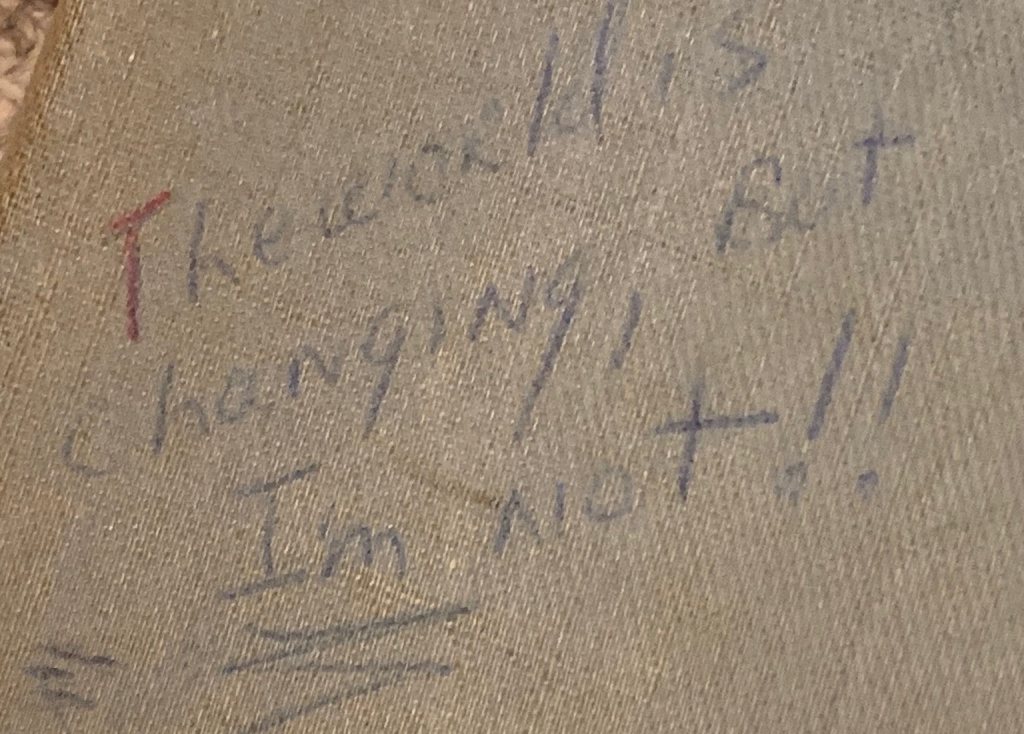

I was a “love it or leave it” kind of guy when I left for college. I was proud to say I was a reactionary. “Better dead than red” I had written on the binder I carried around senior year. It should have contained notes from my classes but didn’t. Just my naïve political proclamations. I also had written, “The world is changing but I’m not!!”

One of the biggest insults that we would hurl in my circle of high school friends was, “You’ve changed.” As if growth of any kind other than physical was a bad thing. I had heard that college could change you and with my limited view of myself and the world at that time, I was determined not to let that happen to me. And at first, it didn’t.

I went home every weekend for the first month or two of school. Home was just an hour and a half away down the Massachusetts Turnpike. If I got an early enough start on a Friday, I’d head toward the entrance of the turnpike on Mass. Ave. after lunch carrying a piece of cardboard with “Hartford” lettered in red magic marker. If I were lucky, I’d catch a ride within an hour or so and be home with enough time for a shower before dinner.

On the days drivers weren’t picking up, or if they were only going half way and you needed to hitch a second ride, the normal 90-minute trip could take much longer and mean missing dinner and definitely the shower. If I didn’t want to chance the vagaries of hitchhiking or if it was raining, I’d shell out the $5.25 – if I had it – for the Greyhound bus.

I wasn’t crazy about spending a lot of time in my dorm room at first. White Hall was not built to be a dormitory. It had been an apartment building before Northeastern bought it in 1960 and it seemed to be held together mainly by the many coats of paint that had been plastered on it over the years. Even when it opened, it couldn’t be classified as luxury living. It featured rooms with sinks but the communal bathrooms were down the hall. Exposed pipes ran across the ceilings. Every year, it was the first home away from home for almost 400 yet to be domesticated guys. It had seen its share of abuse.

We learned diplomacy by trying to determine what TV show to watch in the basement lounge where, after dinner, there were usually about 75 18-year-old males, three channels and one TV. There were the occasional shoving matches on Wednesday nights when we reached an impasse over whether to watch the tried and true “Hawaii 5-0” on CBS or the hip, new anti-establishment show “Then Came Bronson” on NBC. I was a Bronson fan.

Most of us were from the Northeast, but Northeastern at the time was making a big push for international students, especially for its engineering college. In our dorm, there were a bunch of kids from Taiwan. They stuck pretty close together and always played ping-pong on the other side of the dorm basement while a lot of us watched TV.

One night, when nothing good was on the tube and homework was definitely not on my mind, I challenged one of the Taiwanese guys to a game. It was a little like walking into a small town bar and challenging the local sharks to a game on their table.

I held my own at first. Even though I was quickly behind 5-2 and was probably going to lose, I thought I could be competitive. But the fact that my opponent’s friends laughed derisively at him each time I won a point should have served as a warning.

Apparently, my two points were gifts while he was practicing his topspin. After the teasing, he reeled off six straight points for an 11-2 win. The next game was 11-0. Not in my favor. I gave up.

After each trouncing, the Taiwanese students laughed. They might have been laughing about the food in the cafeteria or about the politics of the day, but I was pretty sure it was about me. And it made me uncomfortable.

For the first time in my life, however briefly, I felt like I was in the minority. But for me, the escape from that feeling was easy.

I stopped trying to make friends at the ping-pong table, walked back across the basement and went back to fighting – in English – over what TV show to watch.

In mid-October, roommate Mike broke the news that he was moving down the hall to join Steve, our old roommate. He delivered the news, looking at his shoes and choosing his words very carefully, as if we were breaking off a long and ardent relationship. He obviously didn’t know how thrilled I was. He and Steve had worked out a trade and one of the guys in his new room would move in with me.

The new guy, Kevin, had been the star of his high school basketball team and he walked on at Northeastern and made the JV team. Even though he was only 5’ 6”. He had thighs that were about as big as his chest and he could almost dunk the ball.

Kevin and I got along great. I went to all his games and since the varsity had a pretty decent team, finishing 14-8, I’d stay for their games as well. A game the varsity lost was the highlight of the season for me and the rest of the crowd. One player on the UMass team just sliced up the Huskies. It was obvious: he was much, much better than any other player on the court. I borrowed someone’s program to see who this guy was. A guy named Julius Erving. He later became a doctor. Dr. J.

Kevin was gone a lot at night for practice and hanging out with his team, but during the day, he and his friend, George, a commuter student who was also on the BB team, hung out in our room. Before I had time to resent having this guy in the room all the time, I was drawn down the hall to play cards with some new friends of my own: Pinky, George and Willis.

We met one Friday night while serving a weekend of house detention because we’d all been caught with alcohol in the dorm. Until that weekend, I was still clinging a bit to my old high school life, going to the football games, the parties and hanging with old high school friends who hadn’t left town.

But increasingly, with each visit home, I began to realize that my time in that comfortable social scene had passed. I became an outsider – the old guy at 18 – at social gatherings that had once been “mine.”

On my first night of “house arrest,” I met Pinky. Pinky, because he was the first guy to do laundry and got his reds mixed in with his whites.

We were both out in the hall, smoking a cigarette. He looked like a guy I might have hung out with in high school. Well, I had to look past his deeply pink T-shirt and his long, bushy hair that looked like he had blow-dried it with a heat gun. At least, the T-shirt advertised his high school football team.

“Why are you here on a Friday night?” he asked.

“Aww. I got caught sneaking in a six-pack,” I responded.

“Is that all? George, Willis and I got caught with a case,” he said with a laugh that seemed to acknowledge that their plan had been a bad one from the start.

He then chided me in a friendly, self-deprecating way. “C’mon, if you’re going to break the rules, you gotta go big.”

We had passed each other in the halls for a month without speaking, making silent assumptions about each other. But within two minutes of actual conversation, we knew we shared many sensibilities and were destined to be good friends.

Pinky invited me to a card game down the hall and I was introduced to his co-conspirators, George and Willis and they introduced me to the game of Eights and not incidentally, marijuana.

I didn’t accept that invitation right away. I mean, I’d been to Woodstock where the guy sitting next to me on the hillside had a grocery sack filled with nickel bags and I didn’t accept his offer of a free one.

“No, man,” I had responded lamely. “I’ve had enough.”

Which doesn’t really make any sense. If I had had “enough,” I wouldn’t have known I had had enough.

Bob said I should have punched him.

At Woodstock.

We could have been responsible for the entire festival unraveling. But that illustrates our attitudes at the time.

At Northeastern, these guys became my friends and didn’t seem like some hippie weirdos. George always wore buttoned-down, oxford dress shirts with his jeans and urban boots rather than the ubiquitous flannel of the day. I suppose I should say that we didn’t know that he’d go on to law school and perhaps a judgeship. But we all knew it, even then.

Willis was a good-looking, six-foot tall blonde with a perpetual semi-smile that seemed to signal he was ready for fun, any time, any day. And he was.

Pinky, the guy I was probably closest to, often looked as if he just stepped out of a port-a-potty at Woodstock. Appearance was not a priority for him. Ideas were.

After much thought, I reasoned that if whip-smart George thought it was OK, I could try smoking. So when I wasn’t studying or trying to reconnect with Bethany, who was also going to school in the Boston area, I wandered down to George’s and Willis’ room where we – along with Pinky – played cards– hearts and 8s – and discussed politics.

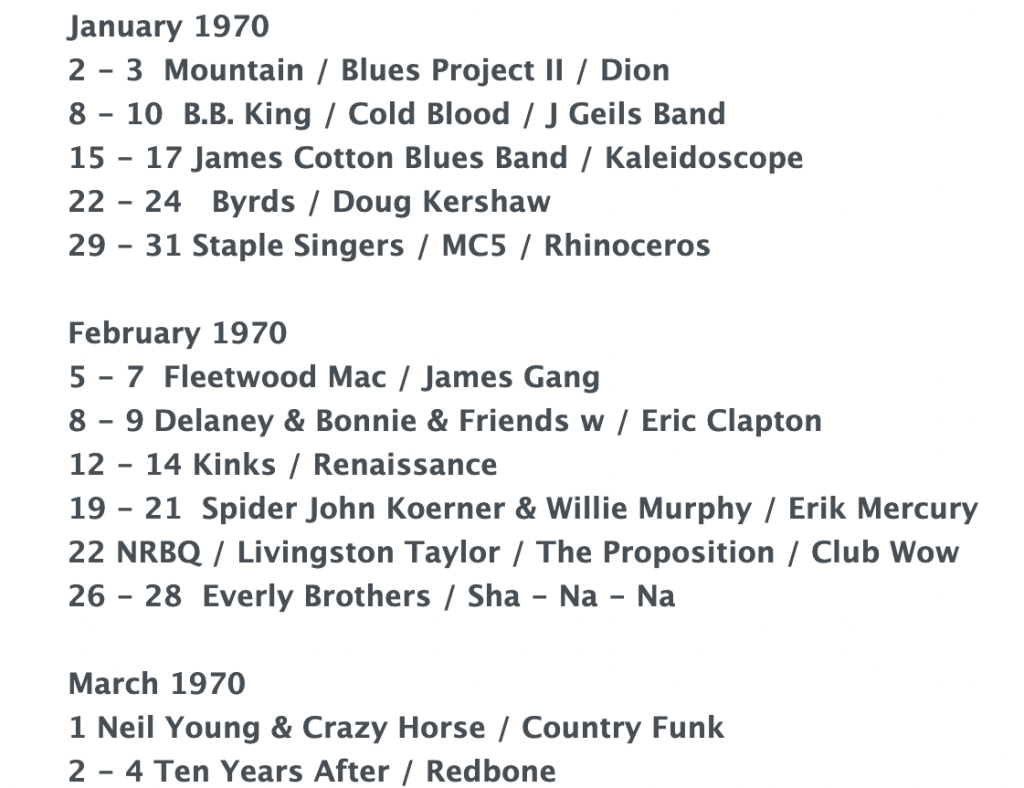

We also began wandering around the streets of Boston, getting to know the city a bit. One of our regular stops was The Boston Tea Party, a venue that often featured well-known acts. None of which we could afford, but we liked to stop by and look at the names on the marquee and imagine we had the money to go in.

On January 22, 1970, we stood outside and saw – and could hear – that The Byrds were the headliners.

“Man,” said Pinky. “I wish we had the cash to see them.”

“I know,” I agreed. “I’ve been a fan since Mr. Tambourine Man. I got their second album as soon as it came out.”

“The one with Oh Susannah?” Pinky countered.

“OK. That sucked, but the rest of the album was good,” I argued.

While we were moaning about not getting in to the show, Willis, the guy who looked like he should be the model on the university’s admissions flyers, had been checking all the doors on the back side of the venue. And he found one unlocked.

He slowly opened it, saw the coast was clear and waved us over. No one inside was watching the door, so we all crept in, undetected. Even though we didn’t have seats or prime line of site, it was a thrill to hear The Byrds. For free. After that, checking the side and back doors on the Tea Party, Boston’s answer to the Fillmore East, was part of our regular weekend routine. Most often, all the doors were locked. But sometimes one was left open.

I stopped going home. My new life began to get interesting.

In the Spring, I began to change from my love-it-or-leave-it political views and got involved with the peace marches. I think a lot of it had to do with the discussions with George, Pinky and a political science TA who taught his students to think from a perspective other than one’s own. Try to see the world how someone else might see it, he suggested. I had never done that before.

The TA was from a DC ghetto and was giving his experiences to a bunch of white, middle-class kids. He explained the 1960s riots and the frustration and feeling of hopelessness of deep poverty – generations of poverty – in the ghetto. It didn’t happen often for me in a traditional classroom, but a light bulb went off in my head. And I could see reasons for actions that I couldn’t before. Actions that are incomprehensible to people raised in a safe, free-from-worry environment like I had been.

Still, I was not fully politically in tune when S.I Hyakawa, the conservative, liberal-baiting educator (and later senator) from San Francisco came to speak in January that year. As the date for his presentation drew closer, there were more and more posters of protest stapled to phone poles and campus bulletin boards. It was hard to walk to class through the quad without being stopped by three or four people handing out flyers the decried Hyakawa and his ideas.

Still, on the night of his appearance, I didn’t even realize it was the night of his appearance. I went out for beer. By then, I knew better how to sneak beer into the dorm, but since I was underage, I couldn’t just by a six pack from the corner store. I had to go a several blocks out of my way, cut through some rather dark alleys to get to the store that I knew would sell to me without an ID.

What I didn’t know was that all the postings and leafleting about Hayakawa’s speech had inspired about 3,000 people to show up on the campus quad to protest it, a lot more than the 400 who showed up to hear him speak.

With the escalation of the war in Vietnam as added motivation, the protestors worked themselves into a frenzy. At some point, some of them decided their voices weren’t getting enough attention. They picked up rocks and threw them. Windows were smashed.

That got attention. From the police.

None of this I knew, as I left the liquor store, carrying my precious twelve cans of beer back toward the dorm. All of it was happening two blocks north, parallel to the route I was travelling. And I didn’t know the police tactical units were mobilizing to halt the protest on the side streets that were between me and the dorm.

With the beer tightly in my grip, I was hurrying down alleys that I didn’t like to walk even in the daylight. I wanted to get back to my room while the beer was still cold and, frankly, the darkened alleys of the Back Bay scared the heck out of me.

I was within two blocks of the dorm and safety when I got to the end the last alley and practically bumped into a full squad of Boston cops putting the finishing touches on their riot gear. They had their helmets on, batons in one hand and Plexiglas shields in the other. They looked like they were from another planet.

The cop closest to me saw me put the brakes on. He raised his baton, more, I think, as a threat than with an intent. Before he had a chance to bring his arm down, I did a 180 and raced back down that alley and circled several blocks deeper into the neighborhood way out of my way to get back to the dorm. Maybe it was obvious that I was carrying beer, but apparently and luckily, the cops didn’t think I was worth their attention.

When I was finally safely inside the dorm and we were sipping our beers, I had to ask George and Pinky what the big deal was. I was a dumbass about that stuff. George took a deep drag on his cigarette and explained that Nixon had begun escalating the bombings and expanding the war. The argument that we were trying to stop communism there otherwise it would spread to America – the domino theory – just didn’t make sense to me.

So in the spring of 1970, protests popped up at campuses all over the country and peace marches took place in all major cities and Pinky, George and I started going to them. Willis came along too, but he was just looking for girls. I suppose you can’t blame him. It was Boston and there were a lot of them.

George began volunteering us to help with the rallies, whether it was handing out fliers, helping with crowd control or starting supposedly spontaneous chants. By April, the rallies were growing larger and more frequent.

Because we kept showing up and doing what we said we were going to do, George, Pinky and I had moved up the ladder of volunteers by the time a massive rally called Moratorium to End the War was being planned for April 15 on Boston Common. We got assigned to rumor control and helped run a phone bank in the basement of city hall.

It might seem crazy that a city would get involved with a protest against the government, but this was, after all, heavily democratic Boston. And the Massachusetts legislature had just passed a legal challenge to the war, signed by the Republican governor two weeks earlier. The politicians there were against the war and President Nixon. They wanted the rally but they didn’t want it to get out of control. And at the time before the internet and instant communication, it was tough to stop a rumor once it gets out there.

But this had been the year of the “Paul is dead” rumor that had college kids all over the country glued to their radios for 48 hours. So we basically lived in the basement of city hall for several days, answering questions about logistics of the rally and who was going to be there, etc.

At one point, some official came in and asked several of us who weren’t on the phone at the moment to come up stairs and say hello to the Boston mayor, Kevin White. He wanted to thank us for what we were doing.

George, the future lawyer and judge, was on the phone and couldn’t get away. I’ll never forget the look of disappointment he shot me as we left to go upstairs for our meeting. After all, he was the brains of our group and got us involved and yet he was missing his chance to meet the rising star of the Democratic Party.

We were whisked upstairs and Mayor White showed us around his office and thanked us for doing what we were doing. We were speechless. At the time, a lot of us thought he was going to move beyond the Mayor’s office to something big. He didn’t, but that’s another story. And not mine.

On the day of the march, 60,000 people showed up, about twice the capacity of Fenway Park. We marched down Commonwealth Avenue and it was wall-to-wall people for blocks.

Boston has about 100 colleges in the area and tens of thousands of students and it seemed as if most of them turned out that day. As did all the prominent Boston politicians including Ted Kennedy. And marches like that went on all over the country that day.

We felt as if we were shouting in unison to the government: Stop the war. But then Nixon came on the news and said he didn’t pay attention to that stuff, that it was just a small number of individuals. He said he paid attention to the Silent Majority. I think by dismissing us, he radicalized some of us.

The war continued and so did the protests. They went on day after day. Every night, after school – and even during the day – there was some form of protest or agitating going on our campus and campuses all over the country.

Then came May 4, 1970. Four students had been shot dead in protests at Kent State. Nine more had been wounded.

For most of the day, we sat, stunned, in George’s and Willis’ room and tried to get what information we could, twisting the dial on the radio. Suddenly we seemed so far away from the people we had been when we arrived on campus just nine months earlier.

I had changed.

When it was time for the nightly news, we didn’t want to face the crowd in the basement TV lounge, so about 15 of us squeezed into Frank Fugazzi’s room because he was the only guy who had a TV in his room. Throughout the year, that’s where we had all met every Sunday night to watch Mission Impossible. This was different. Up until that hour, we had never watched the news together or talked politics with this wider group.

We were silent as we watched the reports about the shooting on CBS. But Frank, still staring at the TV, broke the silence.

“They got what they deserved.”

George, Pinky, Willis and I walked out.

11 days later, 2 more students were killed at Jackson State when police fired on a school dorm.

Then, all hell broke loose on campuses across the country. At first it was relatively small. And school officials thought they could control it. To keep us out of the street and to keep us from clogging traffic on Huntington Ave, the Northeastern administration scheduled bands almost every night on the quad.

The kicker for me – the moment when I knew they were desperate and had no idea how to control us – was when the SGA began passing out joints. These joints were obviously machine made (at a tobacco company?), the best I had seen until some years later when I got my hands on some government issued joints rolled for an experiment at UCLA. I guess they figured if we smoke enough of this high-grade dope, we wouldn’t riot.

But after the Kent and Jackson State shootings, what we had done with youthful exuberance and optimism, suddenly took on a much more serious and ominous tone. The cops who showed up to keep control were no longer representing the establishment, but the enemy. The events in Ohio and Mississippi had us worried and angry that they could at any moment lift their rifles and begin firing.

Then the city started imposing curfews and we had to be off the street by dark. A couple of days later, the order came that we had to be in our dorms by dark and the lights had to be out. Finally, because things had gotten so bad all over the country, with the tension between the students and anything resembling the establishment, Northeastern, along with many other schools around the country, decided to close early. It was a smart idea from the establishment’s point of view: disperse the students.

We were given the option of taking the classes we were in Pass/Fail or taking the grade we were getting at the time. I took a mixture and asked Mom and Doom to come get me as soon as possible. It had just gotten so tense.

All I could think of was getting home and playing golf. I wasn’t a big golfer. But after the last few months of tension in the big city, it represented peace, normality and suburbia to me.

The sudden end of the year meant we didn’t have a final party, didn’t say goodbye or make plans to stay in touch. Although Pinky and I did for another year or two. Willis transferred but did write for a few years, always about his latest girl friend and always in too much detail. Never about politics.

I never saw George again.

Next time: Chapter 28: Summer Work and Sophomore Year.

Categories: My story

Those were the days. I guess today’s college campuses don’t feel the need to protest.

Sent from my iPhone

>