Senior year, I made the Dean’s list.

I finally became the student my parents and teachers had been telling me I should have been all along.

I was loaded up on English and history classes to finish my major and minor and those classes required my two strengths: reading and writing. I didn’t have any science, philosophy or religion classes to weigh down my GPA.

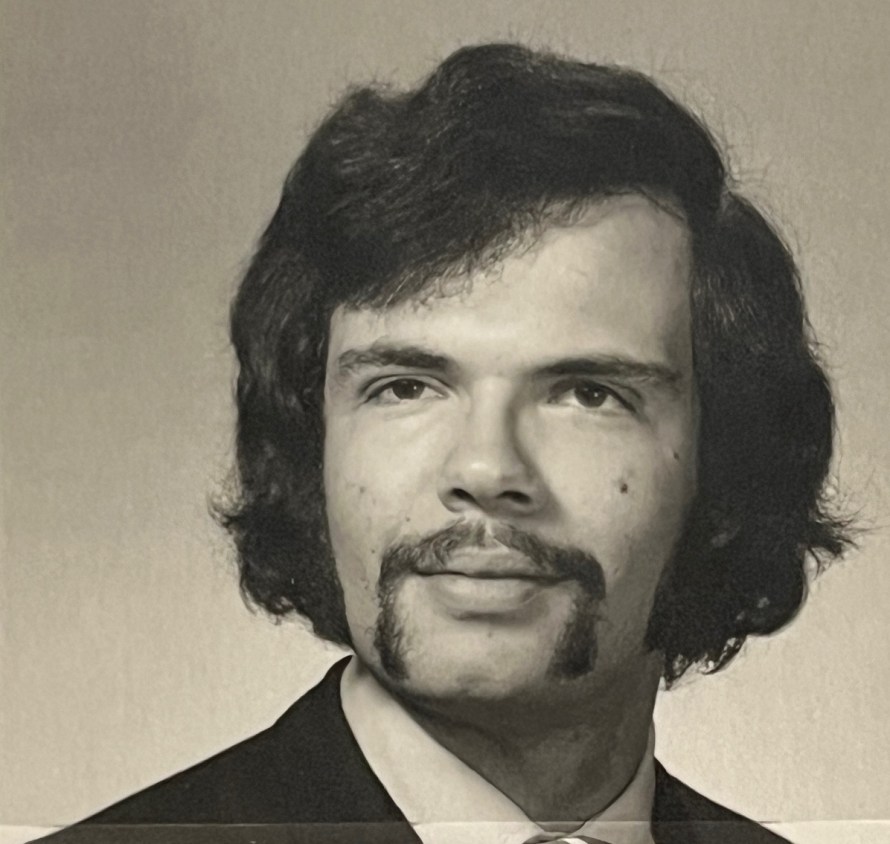

The only blemishes on my record were in the classes taught by Dr. Theodore Edward Crawley, Hampden-Sydney class of ’41. Ned to his friends. Dr. Crawley to us then and forever. He was a legendary figure on campus. His courses were as challenging intellectually as football practices were physically. And just like Coach Robinson back in high school, Dr. Crawley was a guy you didn’t want to disappoint.

I took a course from him every semester during my two years on that campus, two semesters of English Literature junior year and two semesters of American Literature senior year. I earned a D the first semester, a C- the second semester, a C the next and finally, in the spring of senior year, my Dean’s list semester, I was thrilled to earn a C+.

Despite those grades, Dr. Crawley was far and away my favorite professor. I worked hard to earn those grades. Well, maybe not the D. That semester, I was new to the campus and clueless about the rigors of a Crawley course.

While his students often woke up five minutes before their 8 a.m. class, threw on T-shirts and jeans and ran barefoot across campus to beat the school bell, Dr. Crawley was always there early, impeccably dressed in suit and tie, with perfect posture exuding his intellectual rectitude. He stood in stark contrast to many of our professors, including one economics prof who taught in the same room, seated and slouching, and notoriously tapping the ashes from the cigar he puffed throughout class into the top drawer of the desk.

A few of the class brainiacs would show up early and engage Dr. Crawley in conversation about the class readings, trying to impress him with their knowledge and interpretations. I showed up seconds before class began, afraid that I might be pulled into that before-class-conversation if I appeared any earlier and reveal my ignorance.

The only time I did talk to Dr. Crawley outside of class was on the Monday after Homecoming my first semester there. I turned a corner on campus and there was his imposing figure striding right toward me. I didn’t see another sidewalk I could turn down to escape a social interaction and the only building I could dive into to avoid our meeting was “the science palace.” For me to enter that building would have been obvious I was avoiding him.

Dr. Crawley stopped me.

“It was great to see your parents at homecoming,” he said, smiling and almost seeming human and not the god I suspected. “John (Doom) looks just like he did when we were students.”

I hadn’t realized that he and Doom had been classmates and fraternity brothers. I don’t think they spent a lot of time together. Dr. Crawley was two years older and in the glee club. Doom played football. Although they both served in the Navy during WWII.

I acknowledged his comment with a few stammered words and promised that I’d pass on his remark to my dad. I ended the conversation by telling him I was enjoying the school very much but was still trying to figure things out. Dr. Crawley smiled, nodded and then walked away.

Whew, I thought. Either I’ve got an in with the most feared professor on campus or he is now convinced I am an inarticulate idiot.

It was obvious that Dr. Crawley loved his subject and loved teaching it. My classmates and I could read Milton’s “Paradise Lost” or Whitman’s “The Leaves of Grass” back in the dorm and they would often appear to be just words on a page. But then we would come to class and Dr. Crawley would read passages aloud that made those works come alive. He gave us the voice that we needed to hear in our heads when we read such classics.

To this day, I often still hear Dr. Crawley’s voice when reading a difficult passage.

“Gentlemen,” he would say when talking about great literature, “it’s not what you’ve read. It’s what you’ve reread.”

He said there were books by Melville, Twain, and Whitman that he reread on a regular basis because they were so rich and deep one couldn’t possibly extract all their meaning in one or two readings. And he said, you encounter great literature differently at different stages of your life. We envisioned him racing home after classes and rather than spending time with his wife or turning on the TV to catch up on the news and culture of this century, excitedly sitting down to read “Moby Dick” for the 15th or 25th time.

For Dr. Crawley’s survey classes, we read thousands of pages of poems, essays, stories and novels on the tissue thin paper of the Norton Anthologies. His classes were the mental version of wind sprints: Every class that came after them was easier.

One of those classes was focused on F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. Both authors were back in vogue and, as is fashionable from time to time, the hot writers become the subjects of serious study in college classrooms.

As spring break approached, we were assigned a term paper on Fitzgerald. I hated term papers. While I could write as well or better than most of my peers, academic writing was different. It seemed too restrictive for me. I would usually go down to the library basement, find passages where I thought I knew what the egghead authors were saying and then paraphrase what they said. It was probably as close to plagiarizing as you could get in those days.

I wasn’t trying to steal the work. I just didn’t quite grasp the process or the purpose of the papers I was assigned.

When spring break arrived, I was still struggling for a topic. Despite that, I took off for Florida. It was my chance to experience a spring break firsthand, having spent my early teens watching Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon in movies like “Where the Boys Are” and “Beach Blanket Bingo.”

Since I was in Virginia, I figured I was already “down south” and didn’t have that far to go. But it’s a long way to Fort Lauderdale from practically anywhere. Even driving straight through, it nearly took a full day to get there.

I loved the late winter climate of Florida, but not it’s frying pan flatness.

I split the cost of a cheap motel room near the beach with 6 other guys. I bought the most inexpensive, no name beer, didn’t go in any bars and just hung out on the beach all week.

I stretched my meager budget by going to the Howard Johnson all-you-can-eat dinners – there was a different one each night (chicken, fish, meatloaf) – and ate as much as I could, sometimes sneaking out extra rolls wrapped in a napkin for breakfast. Then I’d try to make it through another day drinking beer until 4:30 when I – and a whole bunch of senior citizens – hit the next all-you-can-eat buffet.

The only other thing I spent money on was a Yankee Spring Training game. The weather was perfect, the ball park was intimate, especially compared to Yankee Stadium and, like most minor league parks, you were much closer to the players. You could actually see them without the aid of binoculars. I was easily one of the youngest people in the ballpark, by about 50 years. I remember thinking how great it would be to be retired and go to these games daily.

When I got back to school, the term paper deadline was one week closer and yet I did nothing. It was due after Easter, still a few weeks away. I kept hoping for inspiration to strike. But the gorgeous spring weather made it difficult to focus on that looming deadline. And working my radio show, playing baseball, and attending concerts and parties kept 90 percent of my brain away from that focus, too. The other 10 percent kept nagging, reminding me that I had a big paper due.

Eventually, I tried going to the library again but my brain went into a fugue state as I pulled dusty volume after dusty volume off the shelves, written by Phd.s who, in my opinion, over analyzed the straightforward writing of Fitzgerald. And it was evident to me, all the other guys in my class had pulled the same dusty volumes off the shelves for their papers.

As I walked back to my room from the library, inspiration finally struck. It hit me that my old pal, Clark, the guy I used to walk to elementary school with every day, was at Princeton and president of The Cottage Club, somewhat like a fraternity, but Princeton calls them “eating clubs.” It was the same club that Fitzgerald had been a member of.

Clark roamed the same building that Fitzgerald had roamed. I decided I needed to go to the source.

I could go see Clark and perhaps pick up Fitz’s vibe. Maybe I could go to the Princeton library. It had to have more and better books about Fitzgerald than Hampden-Sydney’s. I didn’t know exactly what I was after, but a road trip just seemed like the right choice.

I arrived late at night but could see The Cottage Club was in a high rent district. The size – it’s roughly 12,000 square feet – and opulence of the eating clubs were evidence that these were no ordinary fraternities. Hampden-Sydney has a lot of rich kids from doctors and lawyers families. They’ve done well for many generations and were going to do well in the future, but Princeton was HSC on steroids. Our Theta Chi frat house could be found in any middle-class neighborhood in the US. The mansions that housed the eating clubs at Princeton would fit in neatly on Newport, Rhode Island’s Bellevue Avenue.

I was greeted at the door by the butler, who offered to take my coat. This was the 70s and all that stuffiness, formality and basic good manners had been tossed out the window. Equality was the word. I was a bit taken aback as he had me wait in the lobby while he called Clark to tell him he had a visitor

Princeton was on spring break that week so we had the run of the mansion for the entire stay. Just Clark and me. And the butler. It was amazing. We drank, played pool, smoked some pot and got inspiration for my paper. Clark took me to a bar in the working class section of Princeton, where the regular folks, not the blue bloods, drank. 15 cents for a glass of beer. Put down a dollar and you were well on your way to getting drunk. We each put 2 dollars down and got plastered.

After Clark went to bed, I went exploring, going from room to room at the Cottage Club until I stumbled on the club’s library. It was in this room that Fitzgerald had begun work on the novel that catapulted him to fame, “The Far Side of Paradise.” Stumbling around the room, I came upon the yearly registers of the Club’s members. I excitedly looked for the class of 1917, that one that might feature Fitzgerald’s picture and biography. As I drunkenly pulled the volumes from the shelves, knocking several to the floor, I saw that one had slipped behind the others. It was published during Fitzgerald’s time at the club.

I was nearly shaking with excitement at my discovery. This is what I had come to Princeton for. I slowly and carefully turned the pages to get to the “Fs.” When I got to there, Fitzgerald’s picture was missing. Someone, surely on the same quest as I, had gotten there first, perhaps the week before or years or decades before and carefully cut out his picture, then hidden the volume behind the others.

I was disappointed but not deterred. I decided not to write an academic paper but a narrative of my visit to the modern-day Cottage Club. I compared what I saw that spring with what Fitzgerald had described 50 years earlier in that first novel. For sources – because a term paper needs sources – I found what I thought were applicable quotes by famous writers like Joan Didion, talking about Fitzgerald or the life of rich people or of Princeton. I was pretty nervous when I handed it in because it was such a different approach for a “research” paper.

A week later, our professor, Dr. Elmore, was at the front of the class talking about the papers and their overall quality, the kind of talk that teachers always feel they must give before handing back the papers. I didn’t hear a word. I just wanted to know whether I passed or failed. But as Elmore droned on about the papers, he began to get excited about one, about how different it was and how interesting and what a fine piece of work it was. It stood out from all the other papers.

He was talking about mine! It was as if I was in 2nd grade again with Mrs. Darrow and I was winning the box of chocolates. Or Senior English in high school with Mr/s Gromelski reading my sentences to the class and she and they were laughing hysterically.

I couldn’t believe it. And then he began to read excerpts. Wow. Mind you, Elmore was a guy from the deep south and really didn’t much trust or like me – a Yankee. He would always say these things that made it seem as if we were still fighting the Civil War and then look at me. His grasp on anything north of Washington DC was very fragile.

He once was talking about New York State as if it were all like New York City. I finally raised my hand to set the record straight, telling him about upstate New York, with the Finger Lakes, the Adirondacks and wine region. He heard my voice correcting his assumptions, but the pained expression on his face told me he didn’t believe a word I was saying.

So while he was praising my paper, he couldn’t help but keep shaking his head, partly in wonder about how much he liked the paper, and partly, I think, because it was my paper.

That moment in that class gave me the confidence to declare myself a writer – if anybody asked. After class, I raced back to my room and began rewriting a short story I had written when I was at Northeastern. A week later, I submitted it to the campus literary magazine and anxiously waited to see if it would be accepted.

Just before graduation, the editors held an assembly to introduce that year’s magazine and announce the winners for best story, poem and essay.

My story got first place! And that came with a 35 dollar check, a lot of money when the weekly beer special – a 6-pack of Falstaff beer – cost just 89 cents. I could now say I was not only a writer, but a professional writer. It was a great, redeeming feeling to walk up to the stage and collect my prize in front of my friends and the professors from the English department. I had been paid for writing at the Courant, but my writing obituaries was basically dictation. This seemed more legit.

Spring of senior year couldn’t have gone better. I had finally figured out college. My grades were good; I scored with my paper, my story, my radio show, I was on the baseball team and even got into a few games. And I had met a girl at the last party of the year.

And the good news was that, because I had transferred, I was coming back in the fall for one last, sure to be glorious, semester.

Until I wasn’t.

Shortly after I got home and had started my summer job at a golf course, I got a letter from school telling me that I didn’t have to come back. I only needed one more course, a biology class, to finish up. I took it that summer at the University of Hartford.

College, and the budding romance down south, was done.

Instead of planning for a final semester of college, once again I was stuck in my childhood bedroom on the third floor on Beverly Road, staring at those old covers of Sports Illustrated magazine that I had thumbtacked to my walls in junior high school.

I really hadn’t given serious thought to my future. I mean to the shape of the next 40, 50 years of my life. Until then, most decisions had been fairly simple such as whether to buy the stereo or mono version of an album to save a dollar, whether to keep my paper route when I got the job at Lincoln Dairy or whether I should go to college so as not to get sent off to Vietnam.

Now Doom wanted me to get a job. A real job, one with a future. We lived in the insurance capital of the world. Aetna’s headquarters was just down the street. So was The Traveler’s. I had been in those offices during my previous summer jobs, installing ceiling tile in football sized rooms with hundreds of cubicles. All the guys hunched over their phones or spread sheets, dressed in white shirts, dark pants with a sport or suit jacket hanging on the back of their chair.

I didn’t want to be a drone filling one of those enclosures. Sure, I might eventually earn enough to afford a beach house or a ski chalet, but I wanted to be a writer. To accomplish that, I needed to see and experience and know things to write about. I had to travel to do that and I had barely been out of New England.

I wasn’t ready for the adulthood that had crept up on me. I couldn’t stave it off by going to grad school. My grades weren’t good enough. And the draft had ended the previous year so the government, thankfully I realize now, couldn’t decide my next step.

I needed a plan, a short term, if not a long term, plan. I decided to work all summer and fall and head to California after New Year’s. I had friends living in Florida, Kansas and my old house painting partner, Tehan, was living in Los Angeles. My big plan was to just go. See what happens.

Never mind that the country was in the midst of an energy crisis that featured long lines at the gas stations. Gas stations that were only opened for limited hours each day when they were open.

Still, on January 12, 1974, I hit the road. It was the beginning of an extended transition, lurching into adulthood.

#######

This chapter marks the end of Alan Sivell’s A Boomer’s Life … part one. Thanks to those who left reviews and commented. If you haven’t left a review on iTunes or what ever platform you are consuming this on, please do. And if you enjoyed these stories, please tell your friends and family. And, if it’s not too much trouble, do more than that. Send them the URL. You know they won’t look it up on their own.

Part two, Lurching into Adulthood, is currently under construction with the help of diaries I kept during my 20s. The plan is to have new chapters begin appearing in the fall.

Until then, thanks for listening or reading or both.

Categories: My story

Great writing Alan! You have an excellent memory to recall all the nuances of growing up. I’m living vicariously through your writing. I wish my life had been half as interesting as yours.